From Incan empires to Escobar and Obama, the coca plant has for centuries been deeply rooted in religion, industry and war. Coveted since ancient times for its naturally occurring, almost superhuman properties, it is today maligned and often misunderstood as the world’s most diabolical drug.

Of the quarter million known plant species on Earth, only a handful have supplanted themselves into modern human society. Rubber, sugar, corn, tea, coffee and spices like saffron, pepper and cinnamon have all helped shape trade routes and colonial expansion. Locally, lodgepole pine and marijuana have helped shape the Kootenays. Both lumber and pot generate income and the odd international kafuffle, but few plants have shaped modern international politics like those of the family Erythroxylaceae — collectively known as “coca.”

Native to the cloud forest that carpets the midriff of the eastern Andes, coca’s thumb-sized, pointed leaves contain 14 natural alkaloids, including benzoylmethylecgonine, that when extracted from the leaf through a process using kerosene and other chemicals becomes known by its pharmaceutical name: cocaine. Depending on whom you ask, the coca leaf and its inherent alkaloids are either critical cultural medicine or highly addictive, culture-destroying devils.

Centuries ago, coca’s medicinal properties made it a cultural lynchpin of the vast, pre-industrial Incan empire. The magic in the leaf fended off thirst, hunger, pain and fatigue. Currently, it is still a cultural staple for many Andean cultures, but congruently coca has also taken a multibillion dollar transformative ride from the cloud forests of the Andes to the streets of Los Angeles, New York, Vancouver, London, Amsterdam and everywhere else on the planet where people love to party.

Today, coca and cocaine are two completely different things. To make cocaine, leaves are first soaked in barrels of solvent, often gasoline or kerosene, to strip the active chemicals from the leaf. Acid is then added to pull the compounds from the solvent, then more caustics folded in to precipitate cocaine base, which is dried and pressed into bricks.

The cocaine base is either further processed on site or smuggled to the next link in the chain for purification. The base is dissolved in either acetone or ethyl acetate and warmed in a bano maria, or hot-water bath. Once the base is fully dissolved, methyl ethyl ketone and concentrated hydrochloric acid are added to precipitate cocaine hydrochloride, which is again pressed into bricks and dried to the form sold on the street. An ultra-addictive, extra-fast-acting coke is made by dissolving cocaine hydrochloride in water and baking soda, and cooking and drying the product into crystals that crack and pop when smoked, hence the term “crack” cocaine.

In the Andes, daily coca use remains the norm in the mountains of Peru, Bolivia, Colombia and Ecuador, where the leaves are chewed, made into a tea or pressed onto the body for aches and pains.

Nowhere are coca’s blessings and curses more evident than in the Bolivian silver- and tin-mining city of Potosi. At 4,090 metres, the city is high even by Andean standards, and for over five centuries it has been one of the world’s highest-producing and most diabolical silver mines. It was here, in Potosi’s sunbaked, dusty market, that I was first introduced to coca.

As the leaf works its mild neurotransmitter-blocking magic, a pleasant numbing begins in my mouth. Nothing more. No euphoria, no dancing lights, no buzz. What’s all the fuss about?

Under a roof of faded plastic tarps, I follow a local guide through Potosi’s market, past vendors selling everything from soccer balls to dried llama fetuses. We need to purchase some bribes to get us into the mines for a tour. At a stall with several waist-high bags of dried leaves, an old woman with a deeply lined face, roughened from decades baking in the Altiplano sun, has greyish-green leaves pasted to her temples as she fills small baggies. “Coca!” our guide exclaims with a grin.

Our saleslady then passes us tiny, paper-wrapped packages containing a dark, crumbly solid. “Llipta,” says our guide, breaking off chunks of the lye for me. “Chew the llipta with the coca leaves to release the medicine. No more hunger, thirst or headache from the high altitude,” he assures me.

I take a palm full of leaves, insert a pea-sized chunk of the suspicious-looking catalyst, and place it in my mouth. My cheek bulges like those of most of the rural Bolivians I have met. Acidic earth, ash, tea and mint make up coca’s unique flavour. As the leaf works its mild neurotransmitter-blocking magic, a pleasant numbing begins in my mouth. Nothing more. No euphoria, no dancing lights, no buzz. What’s all the fuss about?

Llipta reacts with coca leaves to release some of the plant’s biologically active alkaloids at levels high enough to be noticed but low enough that they produce only mild background effects. Snorting a 200-milligram dose of coke delivers the isolated and concentrated cocaine from over 50 grams of coca leaves directly into your system via your lungs, the most effective, non-injected point of entry.

High andean cultures have used coca leaves for thousands of years, chewing it or Brewing it into a tea for headaches, stomachaches, altitude sickness and as a hunger Suppressant. Inca nobles chewed it, and even today local healers read the leaves to Find answers to health troubles.

En route from Potosi’s market to the crumbling mine shafts under the Cerro Rico mountain, also called “The Mountain of Riches,” the terrible wonders of the coca plant become terribly plain. Just inside the mine mouth sit mystical sculptures nearly buried under the daily offerings of coca leaves the miners leave as pleas for safety. To the miners, the leaves hold the power of — or offer a connection to — their gods. Once inside, the men and boys become human mules working 12- to 16-hour shifts on little more than a plastic container of water, some boiled potatoes and cheeks bulging with coca. For, in addition to the rubbery mouth and warm lips, coca takes away hunger and thirst, and locks pain in a quiet room.

[sd_full_bg bg=”#020000″ text=”#1c1c1c”]

The Un-real Thing

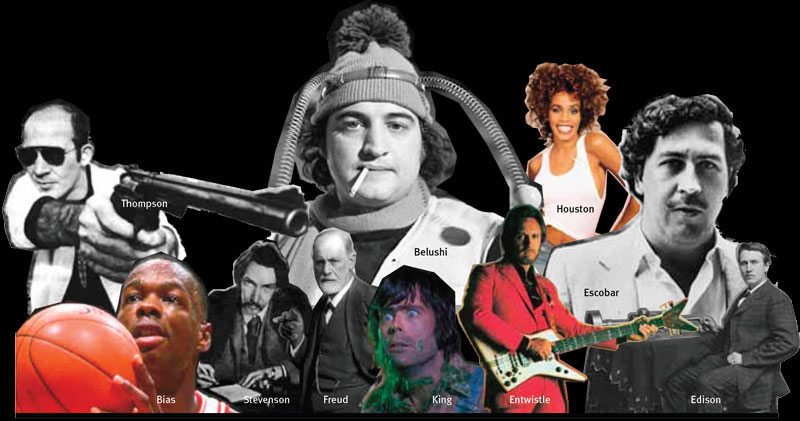

From Belushi to Medellin, a snapshot of cocaine’s victims and global machinations.

[one_third]

High Times, Low Lives

Estimated Number of Global Users

Cocaine: 17.2 million

Ecstasy: 18.1 million

Marijuana 159.8 million

Opiates 17.3 million

Estimated worth of the global cocaine market: $85 billion

Estimated worth of the global criminal firearms market: $1 billion

Per cent of total North American cocaine sales controlled by Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel: 50

Top three drug exporting nations: Afghanistan, Columbia, Peru

Illegal drug-trade contribution to global gross domestic product: 0.9%

Per cent of cocaine that leaves Columbia, via the Pacific: 70; via the Atlantic: 20; on land, via Venezuela: 10

Per cent of revenues earned by Andean cocaine producers: 1; retailers: 65; traffickers: 9; wholesalers: 20 to 25

Global cocaine seizures in 2009: 505 tonnes

Global consumption: 440 tonnes[/one_third]

[one_third]

Dead Or Delivered

Famous lives lost to cocaine overdose/administration

The Who’s John Entwistle, 2002, age 57; King George V, 1936, age 70, drug administered by doctor following a lengthy illness; flamboyant German aristocrat Count Gottfried von Bismark, 2007, age 44; comedian-musician John Belushi, 1982, age 33, (visited by Robert DeNiro and Robin Williams earlier that day), Whitney Houston, 2012, age 48; NBA second overall draft pick Len Bias, 1986, age 22

Famous lives lived despite cocaine use

Psychoanalyst pioneer Sigmund Freud, inventor Thomas Edison, authors Robert Louis Stevenson and Stephen King, journalist Hunter S. Thompson.[/one_third]

[one_third_last]

Ungodly Godfathers?

George Jung: Was the first major US cocaine trafficker in late 1970s. Pricing back then in Colombia: $4,000/kilo and in the US: $60,000/kilo. Jung’s share of the US market in the 1980s: 89%. He was ousted from Medellín Cartel; arrested with 1,754 lbs/796 kgs of cocaine in Topeka, Kansas, in 1994; released to halfway house in 2014.

Medellín Cartel: Controlled 80% of international coke trade in 1980s. Max earnings per week: $420 million. Colombia’s number one export in 1980s: cocaine. Number two export: coffee. Formed their own military organization “MAS” with political and corporate backing, including US-based entity Texas Petroleum, linked to over 240 assassinations.

Pablo Escobar: Colombian who began making and selling cocaine in 1975. In 1989, Forbes notes Escobar, now Medellín Cartel boss, as one of world’s 227 billionaires. Worth: $30 billion-plus. Killed after 15-month operation by authorities in 1993, age 44.[/one_third_last]

[/sd_full_bg]

As world-renowned British Columbian ethnobotanist Wade Davis notes, when it comes to medicinal plants, “the difference between hallucinogen, medicine and poison is often a matter of dosage.” It did not take long for Europeans to work the dosage up to a point where coca products produced more than just numb lips and a superhuman work ethic. Originally available in a French wine called Vin Mariani, the mix of cocaine and alcohol proved potent and quickly became a staple of the mid-1800s well-heeled party scene. Authors, artists and even Pope Leo XIII got into the Mariani wine.

Atlanta pharmacist and entrepreneur Dr. John Stith Pemberton brought this wonder drink to America, but the prohibition movement of the late 1800s stymied his dreams when his coca wine was banned for its alcohol content, not its cocaine. The quick-thinking Pemberton produced a de-alcoholized version and the first Coca-Cola, “the temperance drink,” flowed from soda fountains in 1886. A coke-fuelled frenzy ensued, and moderates pressured the makers of Coca-Cola to remove cocaine from the mix. It took from 1903 until 1929 to remove all traces of cocaine. To this day, the softdrink giant still includes cocaine-free coca leaf extract in its secret recipe. In 2003, the US’s only legal importer of coca leaves, New Jersey’s Stepan Company, imported 175,000 kilograms of coca leaf for Coca-Cola production. The cocaine removed from these leaves is still used for medical procedures, including its use as a topical anesthetic for mouth, ear, nose and throat procedures.

In 1961, coca leaf, cocaine and heroin were listed on the UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, a multilateral agreement designed “to combat drug abuse by coordinated international action.” Coca leaf was included to target not only cocaine production but coca-leaf chewing and coca-tea consumption as well. The convention’s target was to phase out all coca leaf use by 1989. Despite a 1988 addition by Peru and Bolivia that stipulated that eradication measures “take due account of traditional use, where there is historic evidence of such use,” this convention is clearly at odds with the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Countries like Bolivia and Peru have insisted that “coca no es el drogue”: coca is not a drug. “There will not be zero coca, but there will be zero cocaine,” states and restates Bolivian President Evo Morales, a former coca farmer. Morales is famous for chewing coca leaves during a speech to delegates at a 2009 UN summit on drugs. He has demanded repeatedly that the coca leaf be removed from the UN’s list of prohibited drugs. Bolivia’s 2009 proposal to amend the 1961 convention was shut down by 17 of the 182 member countries — including Canada and the United States.

High Andean cultures have used coca leaves for thousands of years, chewing it or brewing it into a tea for headaches, stomachaches, altitude sickness and as a hunger suppressant. Inca nobles chewed it, and even today local healers read the leaves to find answers to health troubles. A short walk in any Bolivian city will reveal little old ladies in traditional dresses and bowlers with coca leaves pressed to their temples or foreheads. Every market has stalls full of giant bags of coca, and most campesinos on the old trails and rutted backroads have chipmunk-like wads in their cheeks. The coca leaf is, literally, everywhere.

In 2007, over 80 per cent of Peru’s coca crop was processed into cocaine, further incriminating the otherwise innocent coca leaf. Due in part to US pressure to stop Colombia’s coca growers, Peru’s share of the world coca production rose to 45 per cent in 2009, when they produced over 119,000 metric tonnes of leaf. Colombia was still the largest cocaine producer, with over 400 tonnes to Peru’s 300 tonnes, but it is not clear how much of that was produced using cocaine base and coca leaves smuggled in from other countries, like Peru.

For the past three decades, Colombia has been the epicenter of the US-based war on drugs. Colombia-based drug cartels collect leaves and cocaine base from plantations throughout Colombia, Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia. The end product is distributed north by airplanes, helicopters and submarines. Human “mules,” often poor people, are used as well. The coke travels wrapped in condoms inside body cavities, the stomach or in luggage. Plane tickets, promises and threats ensure a steady supply of willing mules. As most of us know, trafficking, harsh drug laws and big demand has made some people insanely rich.

Medellin, Colombia-based drug lord Pablo Escobar embodied the modern myth of cocaine. Legends around this kingpin of coke are enough to make you question your career path. His cartel, at its peak, smuggled a daily 15 tonnes into the continental US at a profit of $60 million per day. His fleet of private jets constantly moved drug money back to Colombia from the US, paper currency that required over $2,500 worth of rubber bands per month to contain. He once offered to pay off Colombia’s entire $10 billion debt if they made extradition illegal and gave him a pardon. He did not get his pardon, but the 1991 Colombian Constitution reforms did contain new rules prohibiting extradition, after which Escobar agreed to do some prison time, albeit in an expansive and lavish private cell named “La Catedral.” When he was finally murdered in late 1993, his net worth was estimated to be in excess of $25 billion, making him one of the wealthiest men on the planet.

Since 2001, the US has dropped between $6 to $8 billion on Plan Colombia, a primarily military aid effort to stamp out the country’s cocaine industry. The plan is controversial; Colombian military forces are accused of atrocities against civilians in their push to emasculate rebel groups like Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) and Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN), labelled as terrorist groups supported by cocaine trafficking.

Another Plan Colombia controversy is the widespread aerial spraying of herbicides like glyphosate, also known as Roundup, over suspected coca plantations to kill them. In addition to catastrophic impacts on non-target crops and natural ecosystems, detractors claim it actually increases coca production, as plantations sprang up in new areas. Between 2000 and 2003, fumigation planes chaperoned by military helicopters sprayed over 380,000 hectares of suspected coca plantation — roughly eight per cent of Colombia’s arable land. In addition to the chemical displacement of up to 75,000 people, farmers simply moved into the forests and national parks in neighbouring valleys and provinces. Many also blame the recent upswing of violent narco-crime in Mexico and Central America on the cleansing of Colombia, as the traffickers move north.

While many sources label Plan Colombia as a multibillion-dollar failure, there are some success stories hidden in the jungles. Luis Eduardo Pineda’s family has always farmed. Like many Colombian farmers, they were forced for decades to grow coca on their farm in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta of northeastern Colombia. “The cartels would come find out how much land we had and tell us based on that how many kilos of cocaine paste or coca leaves we would have to deliver, and threaten us or worse if we did not comply,” explains a sombre Pineda. “Sure they would pay us, but not much. Just enough to get through to the next year.”

“The cartels would come find out how much land we had and tell us based on that how many kilos of cocaine paste or coca leaves we would have to deliver, and threaten us or worse if we did not comply.”

— Colombian Farmer Eduardo Pineda

Growing coca and making cocaine: you didn’t have a choice. Now, under Plan Colombia, the choice is which side you fight for. Pineda goes quiet as he rolls up his sleeve to reveal a jagged scar from a bullet during a firefight with a rebel group during his compulsory national military service. At the Pineda farm, he shows us — a group of international travellers — the shed where he and his family once processed the leaves into paste. Now under a thick film of dust, the buckets, barrels and hoses are all that is left of this remote coke lab high in the Sierra Madre Mountains. The chemical smell of gasoline and solvents still fills the mud-walled, tin-roofed structure, and the floor is stained and oily.

Recently, Colombian troops, backed by Plan Colombia, moved in and cleaned up the region, opening it up for tourism and creating new options for the former coca growers. Pineda still works the family farm, but now he fills in the season as a guide, leading small groups of gringos on multi-day treks into the jungle to visit the recently discovered Ciudad Perdida, which is the Lost City — the Machu Picchu of Colombia. It was on one of these tours that he shared his history and his excitement for the future. “This year we are finally harvesting our first coffee crop,” explains Pineda as he proudly shows off hillsides of young plants. “Now, with the cartels all but gone from this area, we can choose what we grow, who we sell to and how much we sell it for.” Plan Colombia seems to then have at least some success. Between 2002 and 2009, kidnappings in the country dropped from 3,000 to 200 per year, and the fighting force of FARC is estimated to have been halved. Even as President Obama slashes the Plan’s budget for 2015, there are murmurings of how to address the recent upswing of violence and illicit drug running in Mexico and Central America.

Despite this, the core conflict around coca remains: Western leaders are stomping down hard on poor farmers thousands of miles away to solve internal drug problems that don’t have anything to do with the traditional use of a medicinal plant.

Coca’s roots run deep in the fertile soils of Andean mountain cultures, and not even the multibillion dollar will of a superpower has stopped its daily use in the mountains of South America. It’s hard to tell if the coca plant will ever be at peace, but it sure seems like it’s not going away.

Dave Quinn

Born in Cranbrook, British Columbia, Dave is a wildlife biologist, educator, wilderness guide, writer and photographer whose work is driven by his passion for wilderness and wild spaces. His work with endangered mountain caribou and badgers, threatened fisher and grizzly, as well as lynx and other species has helped shape his understanding of the Kootenay backcountry and its wildlife, and help shape his efforts to protect what remains. His writing and photography has helped fill the pages of publications such as British Columbia Magazine, Westworld, the Financial Post, Backcountry, Adventure Kayak, as well as the Patagonia and MEC catalogs.

Related Stories

Backyard Booty Cometh…Again

It was another glorious evening of multimedia marvelousness. The 6th Annual Backyard Booty at Nelson's Capitol Theatre.…

Powder Highway Ultimate Ski Bum Contest

We had to post this simply because it features KMC Editor, Mitchell Scott, in his formal acting debut. The contest is…

The Gathering at Red Mountain

This upcoming Easter weekend RED and POWDER Magazine are presenting the 2nd annual Gathering at RED. Come hang with…