Pack your blister gear and your favourite deck of cards — the next two weeks will be one of the biggest physical, social and spiritual experiences of your life. For those devotees of winter and wild places, there’s no pilgrimage deeper than the ski traverse. Join KMC’s pious scribe as he slides to the edges of inspiration and belief.

Story by Dave Quinn. Photos by Kari Medig

Go forth, sons and daughters of the mountains, and seek to fill three cups. One shall be the Cup of Wilderness, and it can only be filled by immersion in the world the way it was meant to be — natural and unchanged by humans. The second shall be the Cup of Camaraderie, which is filled with the closeness of companions for long periods in high-stakes, inspiring terrain. The third, and most important, is the Cup of Self. Only by drawing your well near to dry, digging down to the bedrock of your physical being and exposing your frayed edges to the mountains, can you fill this cup.

SEVEN ANT-LIKE SPECKS crawl up the steep, open avalanche slopes at the headwaters of Rossland Creek, in the Central Selkirks, on our seven-day traverse of the Goat Range. We are torn between spacing out for safety, and staying close to one another for the perception of the same.

Our feet groan, blistered and corpse-like, after days of sweat-saturated imprisonment in plastic ski boots. The ache in our shoulders wrestles for dominance with the searing burn where our heavy pack straps rub. Lips and noses are doing their best bacon impressions after a few days on snowfields in the hot spring sun, and every muscle seems to protest each inch we travel, whether it is balancing on skins up a frozen slope or breaking trail in a shady, north-aspect valley. Avalanches, cornices, creeks and crevasses wait for a single misstep. With the weight on our backs, even a simple caught edge can pop a knee or send you sliding down an icy slope of doom.

Multi-day ski traverses entail setting out for days or weeks into wild mountains in full winter conditions. The snow and the cold, while they add their own layers of risk, also make travel much easier in many ways, by covering alder, devil’s club, small creeks, glacial crevasses and other obstacles that make off-trail travel an impossibility, or at least really unpleasant, during the summer months. Your own shelter, a warm sleeping bag and sleeping mat, extra warm clothes, and a stove and fuel, plus mountaineering equipment, all must be carried on your back.

“Unlike our daily lives, every single decision you make out there has an impact. That reality creates a clear line between black and white, almost like a hyper-real binary system.” -Kari Medig

On a traverse, each morning boils down to a daily ritual whose only comfort is its familiarity. Awake to the beep of a watch alarm, the ache of dehydration countered only by the ironic throb of a dangerously full bladder. Peel yourself from a toasty sleeping bag, careful not to knock the ice from the inner tent walls onto your tent mates. Pull on down jacket, ski pants, and slip into down booties. A familiar pump and spark lights the camp stove to melt snow for the day’s water, and more importantly, coffee. Ski-boot liners frozen solid are stuffed inside still-warm sleeping bags in the hopes they will at least partially thaw before feet are wedged into them. Use frozen fingers to pack up camp and stuff a rehydrated breakfast into protesting stomach that needs the calories.

But hours later, laying trail and trading turns with your closest friends as far from the rest of the world as you can get, nothing feels more divine.

Most die-hard traversers are seeking to fill up their personal buckets; they’re forming truer versions of themselves. Like the Buddhist pilgrimage to Mount Kailash or the Muslem mission to Mecca, ski tours are essentially a vehicle towards enlightenment through a conscious choice to challenge yourself among fellow believers. On our pilgrimage, we’ve even got the loving company of our dogs, which proves helpful. On the final ascent from Rossland Creek to the McKean Col, our canine companions Maya and Chewy key into something above us on the ridge. Our eyes strain upwards, hoping for a glimpse of the range’s namesake mountain goats or maybe a rare wolverine sighting. But instead two of the brown boulders melting into the sun on the steep, snowy ridge begin to move; it’s a mother grizzly and her cub — right on our intended route. A low, rolling groan from the mother griz reaches our ears, and we pull out the maps to look for an alternate route to the col.

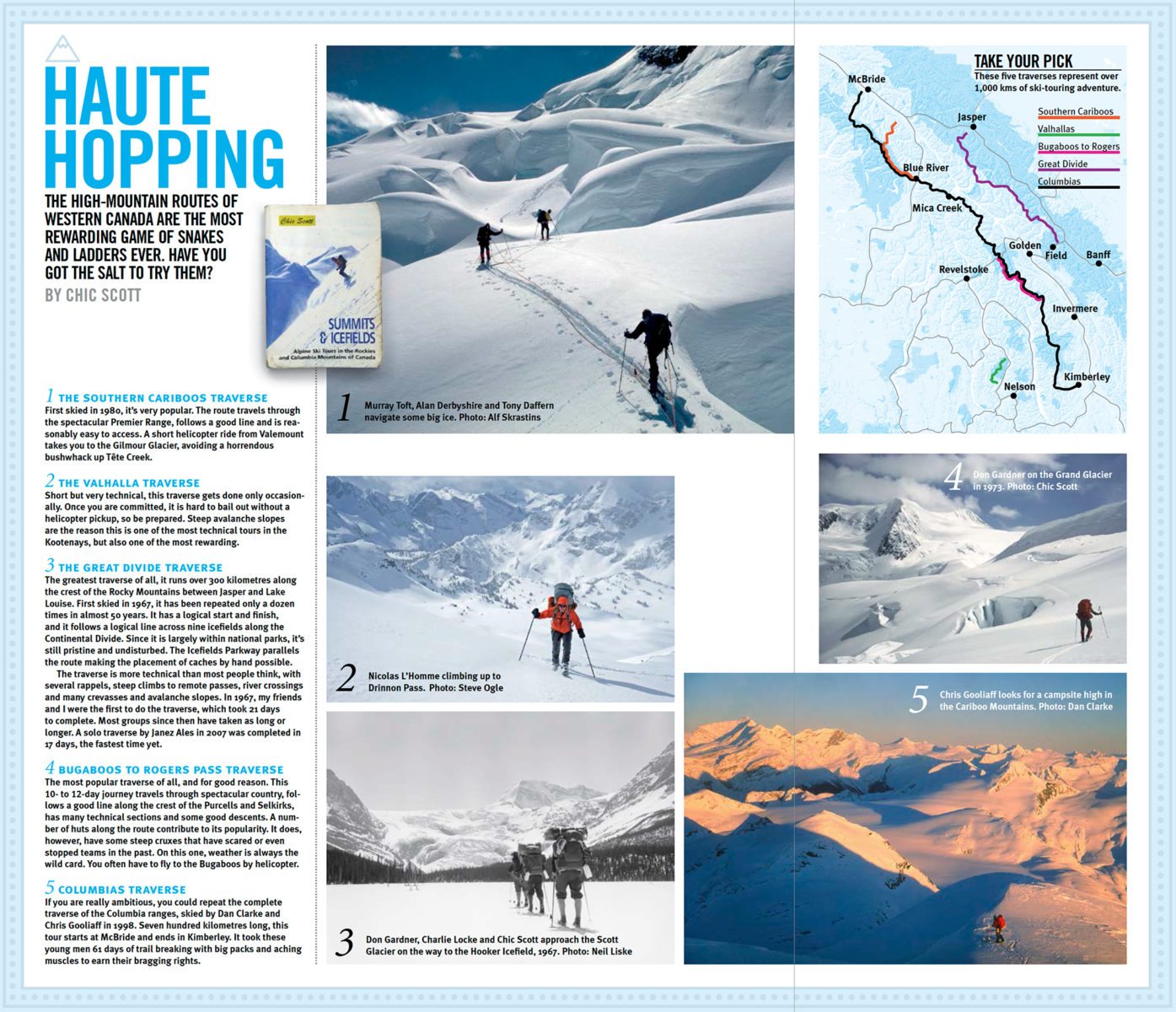

STEVE SMITH is one of the godfathers of modern ski touring in the Columbia Mountains. While others pioneered major ski routes — known as the “grand traverses” for their complexity, the required commitment and the stunning terrain through which they pass — few showed Smith’s dedication to the traverse specifically or connected so many mountain ranges with a ski track. Canadian mountain historian Chic Scott’s first edition of Summits and Icefields contains an entire section entitled “Steve Smith and Friends,” dedicated to these 1970s hard men.

Between 1977 and 1983, Smith completed ski traverses of the North and South Rockies, North and South Cariboos, North Selkirks and North and South Purcells. He also took part in a ski expedition to climb and circumnavigate Mount Logan in 1979 that was the first Mount Logan expedition since 1925 to summit without aircraft support. “There’s something about having a passion for wilderness and wild untouched places that formed my drive to undertake expeditions on skis,” explains Smith. “But to me, the remarkable thing was that, for about a decade, I was not alone in that passion. There were these other individuals who somehow entered my life back then, complete weirdo types who got the same kick out of exploring wild country under their own steam as I did.”

For Smith, the essence of the traverse was the bond it formed with his fellow expedition mates. “My old friend Scott Duncan used to say that going to climb a big mountain somewhere was as much about the journey to that mountain as it was about climbing the mountain itself,” says Smith. “Maybe that’s also why we liked the idea of doing those expeditions under our own steam without caches or food drops or helicopter access. It just fit with the richness of the wilderness setting and the whole business of being responsible for our own well-being and safety.”

As a modern Kootenay ski bum whose photography takes him around the world, Kari Medig agrees with Smith, but adds his own take on the powder pilgrimage. In addition to a host of shorter traverses, in 2002, Medig took part in the northern half of the 2,000-kilometre Vancouver-to-Skagway traverse, the longest ski traverse ever completed, then continued on another 700 kilometres to link up the Fairweather and St. Elias Ranges, summiting Mount Logan on the way as the token male on an all-girls expedition. “For me there is something aesthetic about that simple ski line through complicated terrain, like putting yourself into a giant puzzle,” he explains. “Mountains are a place of real honesty. There is no trick, no fooling around. You have to be on the ball, in your best form.”

Medig sees mountains as a door to a reality that, for him, does not exist in everyday life. “Unlike our daily lives, every single decision you make out there has an impact. That reality creates a clear line between black and white, almost like a hyper-real binary system.”

There is also an innate sense of reward for scraping the bottom of the energetic jam jar — a feeling of renewal.

A familiar pump and spark lights the camp stove to melt snow for the day’s water, and more importantly, coffee. Ski-boot liners frozen solid are stuffed inside still-warm sleeping bags in the hopes they will at least partially thaw before feet are wedged into them.

“On a ski tour you really dig deep, burn out the carbon,” says Medig. “It’s one of the many aspects of a long tour that lets you connect deeper to yourself, and deeper to your companions, and when you do get back to life and start to recharge, the feeling of elation can last a long time.”

All these things are done within the setting of a smaller group, making decisions with friends, building a closer, more real relationship.

One difference for ambitious adventurers these days, though, is that many of Smith’s and even Medig’s traverses cannot be completed in the same manner they originally were. Deforestation and forestry roads have made access far easier, practically everywhere. A boon to most, for some it softens the experience. In Smith’s era, a scant three decades ago, every ski tour, or even the approach to one, was an epic challenge.

“In the mid-70s,” explains Smith, “unless you planned to use a helicopter, getting in and out of the remotest parts of the Rockies and the Interior ranges was an exercise in itself. . . . The wilderness was contiguous and largely free of cut blocks. Nothing had changed in those places since the days of the first mountaineering pioneers and surveyors.”

These days, outside of a few small protected areas like the Purcell Wilderness Conservancy or our national parks, logging roads and cut blocks go to the back of every single valley. Along with this come snowmobile access, mechanized backcountry operations, more people and less solitude. For the purist, it can sometimes feel as if what is being sought has been sullied. Then again, it might just be a reason to push deeper.

BACK IN THE Goat Range, even the eroded wilderness provides clay for self-sculpting. The epic, ski-carrying slog out — in plastic telemark boots — down the washed-out Poplar Creek forest road is, oddly, as satisfying as the daily, 1,000-metre powder descents we’ve just left behind us.

After all, not only does wilderness have a variable definition, but it is just one of many motivators for powder pilgrims. Perhaps, in this modern click-powered digital world, connection to yourself and others is an even more powerful driver than it was in the late-70s and offers more powerful rewards. Even the easiest traverse in the nicest weather and most stable snow still fills people’s buckets. Weeks later, typing away at our computers, or back behind the wheel, our minds still go euphoric with even the slightest thought of our time in wild winter.

We are seekers, willing to drop everything for the tour. It is something so powerful that it carves the sunbaked smile lines a little deeper each year as we belly laugh our way through yet another pilgrimage. Here, the journey is what matters most, so we keep taking it.

Dave Quinn

Born in Cranbrook, British Columbia, Dave is a wildlife biologist, educator, wilderness guide, writer and photographer whose work is driven by his passion for wilderness and wild spaces. His work with endangered mountain caribou and badgers, threatened fisher and grizzly, as well as lynx and other species has helped shape his understanding of the Kootenay backcountry and its wildlife, and help shape his efforts to protect what remains. His writing and photography has helped fill the pages of publications such as British Columbia Magazine, Westworld, the Financial Post, Backcountry, Adventure Kayak, as well as the Patagonia and MEC catalogs.

Related Stories

Ski Your Ass Off

Winter is upon us. But as we look to the future, it's not a bad idea to drift back into the past. The glorious, super…

New Ski Descent of Epic Chute on Mt Brennan

Four Nelson, British Columbia, residents have successfully skied what appears to be a new line off Mt Brennan in the…

History of Ski Aerial Acrobatics

One of the most influential ski films of all time. Dick Barrymores documents what started freestyle skiing. From 1969…

Powder Highway Ski Bum at SWS

Chris Tatsuno has done an amazing job chronicling his Ultimate Ski Bum Powder Highway winnings. In this episode he…

Powder Highway Ultimate Ski Bum Contest

We had to post this simply because it features KMC Editor, Mitchell Scott, in his formal acting debut. The contest is…

Powder Highway Ultimate Ski Bum Vlog

We've been getting lots of requests from KMC readers as to the whereabouts and current activities of the Powder Highway…