From Pemberton to Mazama to Revelstoke, when skins and sweat are not enough to outrun the crowd, some ski tourers are heading for the sled. Are snowmobiles an inevitable mode of adventure for those yearning to go deeper and farther faster? By Ryan Stuart.

KC Deane perches on the edge of a mountain face he’s been dreaming about skiing for years. The fluted off-camber line is guarded by fear. If Deane makes a bad turn, falls, gets hit with avalanche slough, or just goes a little too far left, he’ll go over a 45-metre (150-foot) cliff, accelerate rapidly, and land flat. It’s the kind of aesthetic and challenging line that inspires him. Being the first to lay tracks here makes it even more special. He’s moments away from the highlight of his winter.

But first he had to find it. Deane spent many hours exploring the Coast Range north of Whistler, British Columbia, before he stumbled on this remote zone. “Seeing what’s around the next ridge or up that logging road spur is a big part of why I love the mountains,” says Deane, a professional skier. “I love exploring and finding new places to ski. It’s what keeps it interesting.” Then he attempted the line several times, always aborting because of conditions. But today everything is perfect: the snow, the stability, and the morning light. When he finally drops in, the run is glorious — ski-porn dreams. When I ask him what piece of equipment made that run possible, Deane doesn’t credit his skis or waterproof jacket. Deane’s moneymaker is his dirty, loud, stinky, fossil fuel-burning snowmobile. And he loves it.

The best skiing and snowboarding happens in the backcountry. Increasingly, those lines are accessible via snowmobile. When you watch a ski or shred flick from the Pacific Northwest, most of the terrain you see has been accessed by snowmobile. “For a backcountry athlete, a snowmobile is essential for being able to get out and efficiently find new areas for shooting and filming,” says Deane. “In a lot of the film segments people think we used a heli. But that’s not really feasible unless you have a big budget.”

Not long ago, most backcountry users hated snowmobiles. Maybe they still do. Skiers and snowboarders heading into the backcountry were there to simplify their passion, escaping the noise and crowds of ski hills for the solitude and clean air of the backcountry. Meanwhile, older two-stroke snowmobiles were loud and polluting. By some estimates, they emit as much hydrocarbon and nitrous oxide as 100 cars. Irresponsible and uneducated sledders harassed wildlife and tracked up cat, heli-ski, and backcountry touring tenures and ignored non-motorized zoning.

Then the snowmobile community cleaned up. More efficient and quieter four-stroke engines reduced the environmental footprint. Clubs educated sledders and enforced etiquette and responsible riding behaviour. Just as the snow settled between human and motorized users, interest in backcountry skiing and boarding exploded. The number of people backcountry skiing has nearly tripled in the last decade, according to Snowsports Industries America. It remains the fastest-growing aspect of skiing and snowboarding. Every major ski brand makes backcountry gear. At Mt. Baker Ski Area in Washington, the rush to ski the slackcountry is almost as fierce as the in-bounds terrain. The nearby back-country is often skied out the day after a storm. In other places in the state, like Steven’s Pass, finding fresh snow and a lonely mountainside means logging 3,000-metre (10,000-foot) days. That’s something only the truly fit and highly motivated can pull off. With a snowmobile, just about anyone can.

And they do. Annual sales of new snowmobiles increased more than four per cent between 2015 and 2016, according to the Canadian Council of Snowmobile Organizations. While no one tracks sled-powered skier numbers, the anecdotal evidence is conclusive. In the Mazama Valley, located on the east side of the North Cascades in Washington, a snowmobile has become standard for skiers. The Washington State Department of Transportation doesn’t plough Highway 20. The excellent ski terrain along the road can only be accessed with a sled. Locals leave their sleds at the trailhead. Every winter there are more of them. The main gig of the North Cascades Mountain Guides is snowmobile-assisted ski-touring trips into that terrain.

The best skiing and snowboarding happens in the backcountry. Increasingly, those lines are happening via snowmobile. If you’re watching a ski or shred flick from the Pacific Northwest, it’s almost 100 per cent snowmobile access.

In the Whistler area, the Soo River drainage was once a reliable place on storm days, says Deane. Athletes looking for fresh lines to film were almost guaranteed to find the tree-skiing and pillow-line playground unspoiled. But then a few too many friends let their friends in on the secret. Instagram posts did the rest of the work. Now it’s a hectic spot. This pattern is repeated all over the West, as sled skiing grows in popularity.

BACK IN THE WHISTLER backcountry, Deane is skinning up the mountain again. After knocking off the exposed line first thing in the morning, he skied two others before moving across the valley to catch the afternoon light. The team will shoot and film another three lines before sledding out in the dark.

Today’s been an ideal day, and that’s partly because there wasn’t another snowmobile in earshot. Just like almost everyone else, Deane prefers the sound of the wind to the whine of snowmobiles. And it highlights the ironic cycle of growth in sled skiing: to escape a busier backcountry, skiers are buying sleds in such large numbers that they have to travel farther to escape the other sled skiers. “When I’m on the sled the noise doesn’t bother me,” he says. “But when I’m hiking it is obnoxious.”

The need to have a snowmobile to get away from other skiers and snowmobilers is upending the old rules of staying safe in the backcountry, says Jeff Hambelton, an avalanche educator, snowmobiler, and splitboarder from the Mount Baker area. “The capability of mountain sleds today compared to five years ago is amazing,” he says. “Even a beginner can now go so much deeper, faster, and sooner after a storm than ever before. It’s a challenge to our whole group.”

Breaking down and running out of gas are always potential issues. When he’s sledding, Hambelton brings everything he needs to spend a night out, something he’d never do on a ski-touring mission. But he’s more concerned about avalanches. Snowmobiles are heavier objects than skiers, so they’re more likely to trigger a slide. And because they travel such long distances compared to human-powered travellers, they encounter a variety of avalanche conditions throughout their day. If something goes wrong, ski tourers can potentially be much farther away from help.

With so many new snowmobilers in the backcountry, accidents are inevitable. Four snowmobilers died in avalanches in the state of Washington last winter, mirroring an uptick in avalanche incidents involving sledders in British Columbia and Alberta. The growth in sledders motivated the Washington-based Northwest Avalanche Center (NWAC) to tweak its forecasts. Avalanche forecasters used to collect snowpack and avalanche data on skis, but in the last five years, forecasters increasingly use their own snowmobiles. The centre is planning on buying its own. “The people using our forecasts are going farther and farther out there, so we need to go farther and farther,” says Scott Schell, executive director of NWAC. “Using a snowmobile is the only feasible way for us to gather data deep in the backcountry.”

Hambelton, who will offer snowmobile-specific avalanche courses next winter, thinks there’s an opportunity for skiers moving to sledding to help the snowmobile community become more avalanche aware. “We’ve been studying avalanche stuff a lot longer than most sledders,” he points out. “I think we can move forward more intelligently if we reflect upon the lessons the ski-touring community has learned in the last 10 years.” Human factors like group travel, decision-making, and the feeling of scarcity in a busier backcountry are at the top of his list. He’d like to see a mentorship culture created, where the more experienced teach the newbies. And he thinks it’s the responsibility of new snowmobile owners to join local snowmobile clubs, if for no other reason than to be counted.

In the Mazama Valley, located on the east side of the North Cascades in Washington, a snowmobile has become standard for skiers. The highway department doesn’t plough Highway 20. The excellent ski terrain along the road can only be accessed with a sled.

In the US, the Forest Service allocates funding for backcountry road maintenance and other projects according to the number of users. For the last four years, one of the four access roads for snowmobiling around Mount Baker has been washed out, making it unusable for sledders. The number of snowmobiles has doubled in the area in recent years, Hambelton reckons, but most don’t join the local club, so fixing the road remains low on the priority list. “I can’t think of a better tool for getting into the backcountry than a snowmobile,” he says. “But with privilege comes responsibility. If we want to maintain access, we need to get involved in the process.” It’s important because the pressure to find new places to sled and ski isn’t going to let up any time soon.

Noah Maisonette, a 24-year-old ski bum, grew up in Banff, Alberta, but spent the last two winters in Revelstoke, British Columbia, chasing the dream of getting paid to ski. The first winter he was happy to ski the resort and ski tour. But last year he joined his buddies and bought a sled — and a truck to move it around. “I saw the mind-blowing terrain my friends were accessing so easily with sleds,” he says. “All the pros I look up to are using sleds…I could ski tour some of the same terrain, but I’d be absolutely exhausted by the time I got there. Buying a sled seemed like an essential move if I wanted to move forward in the game.”

To land sponsorships, Maisonette says he needs to ski challenging and unique lines. “The front country, slackcountry, the stuff close to the road, it’s been overshot and over skied,” he says. And there’s the reward of exploration. “Once you’re out there exploring somewhere new, you just want to keep going,” Maisonette says a little wistfully. “You keep pushing, hoping you find the next magical place.”

Anyone can drive a snowmobile up a packed road. Following another track on a logging road takes a little knowledge. Riding in deep powder, through trees, and up slopes requires skill and technique learned through experience, just like skiing. Dutch Simpson, a cinematographer and producer for Teton Gravity Research, a ski and snowboard film company, says everyone they work with needs to know how to drive a snowmobile. “If [athletes] can’t sled, it’s usually a deal breaker,” Simpson says. “Being a good sledder ultimately dictates how productive the skiing and filming is. You can’t get shots if you’re always stuck.”

It’s undeniable that snowmobiles open up the backcountry. “They’re almost as good for accessing terrain as a helicopter,” Simpson continues. “But a lot cheaper and more reliable. Whether the weather’s good or bad you know you are going to get something.”

It’s the same reason skiers like Maisonette and Deane love their sleds. They know when they head out on them they’re going to find untracked snow. But they’re also conflicted about what the snowmobile costs them, and not just in dollars. “When you’re sledding, the mountains just rip past,” Maisonette says. “You don’t get the same feeling of immersion, the feeling of being a small person in the big mountains.” Then there’s the environmental aspect. “Snowmobiling goes against what we as skiers should stand for,” he continues. “I want to keep the snow forever. Buying fuel, running a snowmobile around the backcountry, and the truck to haul it: we’re part of the problem. It’s hard to justify. I’d rather skin. But I also want to ski cool shit right now. And the reality is . . . nothing beats a snowmobile.”

Ryan Stuart does not own a snowmobile.

Ryan Stuart

Ryan Stuart has been fascinated by the natural world since he was a kid, and he’s now sharing this interest through his freelance writing, which he does from Comox on Vancouver Island, British Columbia.

Related Stories

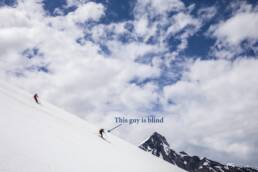

Tyson Rettie is taking blind people backcountry skiing. This is how.

With his Braille Mountain Initiative, Tyson Rettie is introducing visually impaired skiers to the backcountry. By Ryan…

Skiing World Loses a Bright Light: Dave Treadway Perishes in Backcountry Accident

It's with heavy hearts we share the loss of legendary Canadian skier, and our bud, Dave Treadway. Rest in peace,…

Tree Skiing, The Sweetgrass Way

So many questions...how did they do it? How long did it take? Where was it filmed? The answers will be available next…

#BackcountryLikeABoss Contest Winner

For the past two weeks you've been sharing with us your tips, pics and vids as part of the #BackcountryLikeABoss…