Ayahuasca, peyote, Psilocybe semilanceata, and Turbina corymbose are not household names or readily available at your local pharmacy. But Western culture is beginning to embrace the emotional, spiritual, and even physical healing properties of largely illegal hallucinogenic plants. KMC Managing Editor Vince Hempsall travels through the portal of ancient Amazonia for a glimpse into the controversy, and his own unknown.

April 6, 2020 update: The “My Back 40” podcast recently featured Vince and his ayahuasca journey. You can listen here. The 25-minute mark is when the discussion about ayahuasca starts.

Many beautiful things enhance this low-ceilinged room, but the crinkled plastic two-litre bottle stripped of its label is not one of them. Candlelight reflects off wooden artwork and plaster statues, including one of Ganesha, the Hindu god of new beginnings. The colourful Thai cushions we’re seated on are a contrast to the grey clouds outside, hanging low in a darkening sky. Across from me sits a tanned medicine man named Chuck,* who is hovering over a shot glass and the bottle, which is full of a reddish-brown liquid. Some call it “yage,” but most know it as ayahuasca, a hallucinogenic derived from two plants. In a low voice, Chuck explains the structure of the night’s ceremony, then says, “This is serious work. But we laugh a lot,” and breaks into an infectious cackle. Soon we’re taking turns swallowing a small dose of the liquid, which has an earthy tamarind taste. It’s not unpleasant, but later that night it will cause me to endure a horrific vision and weep uncontrollably. And I will be happy for it.

Consider for a moment the impact plants have on your life. This magazine was once a tree. Your jeans came from a shrub. The air you’re breathing is produced by both trees and shrubs. We cannot live without plants, but somehow we’ve lost touch with their importance. We’ve plundered, synthesized, and commodified their properties to create everything from your morning espresso to Aspirin. Yet we’ve never been unhappier. The World Health Organization estimates that by 2030, depression will be the most prolific health problem in First World countries. And modern medical solutions, such as prescribed antidepressants, don’t seem to be working. Since Prozac was introduced in 1987, suicide rates in the United States have risen almost 50 per cent, and Statistics Canada reports that among 15-to-24-year-olds, suicide is the second leading cause of death, after accidents.

To counteract this epidemic, some health-care practitioners, researchers, and proselytes are seeking a cure in the form of plant medicine, specifically those species of flora and their byproducts that trigger psychedelic experiences and affect consciousness, such as peyote and magic mushrooms. Also, Banisteriopsis caapi and Psychotria viridis, two innocuous Amazonian plants that, when combined, create the powerful brew ayahuasca. Most of these plants are illegal in Canada, but people are nevertheless turning to them in increasing numbers, especially in alt-culture enclaves like the West Kootenay. Can plant-based medicine be a cure for mental-health issues and psychological distress in British Columbia and beyond? Or is it just another way to get high?

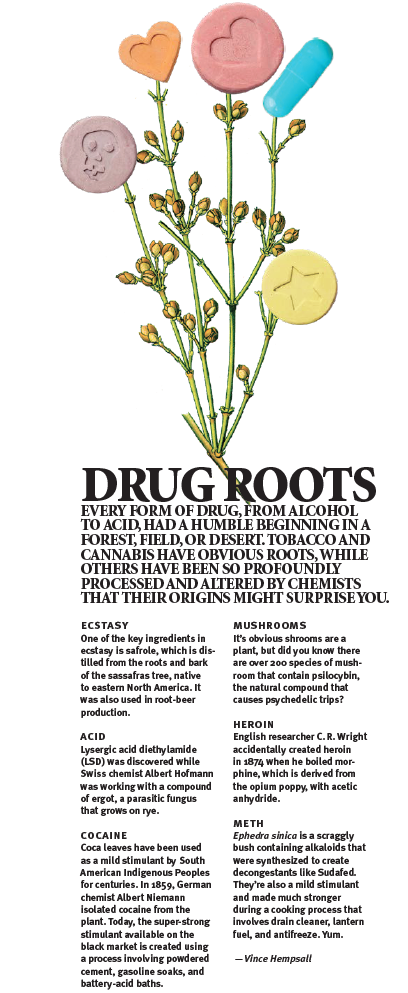

One institution that has embraced plant medicine is the Imperial College of London in England, which opened the Centre for Psychedelic Research in April 2019. Some of the clinical trials taking place there compare psilocybin-mushroom therapy with conventional drug treatment. Others incorporate new technologies, such as neuroimaging equipment, to map the impacts of various substances on the brain. The centre’s director, Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris, believes psychedelic experiences might facilitate neuroplasticity, a temporary rewiring of the brain’s synapses, and could therefore be used to alleviate disorders characterized by mental rigidity. Closer to home, the Canadian division of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies is at the forefront of using methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), originally derived from the sassafras tree, and psilocybin to treat post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. At the same time, Vancouver-based medical doctor Gabor Maté is contributing to a documentary about how ayahuasca can cure addiction. Yes, it seems the ancient science of plant medicine is trending.

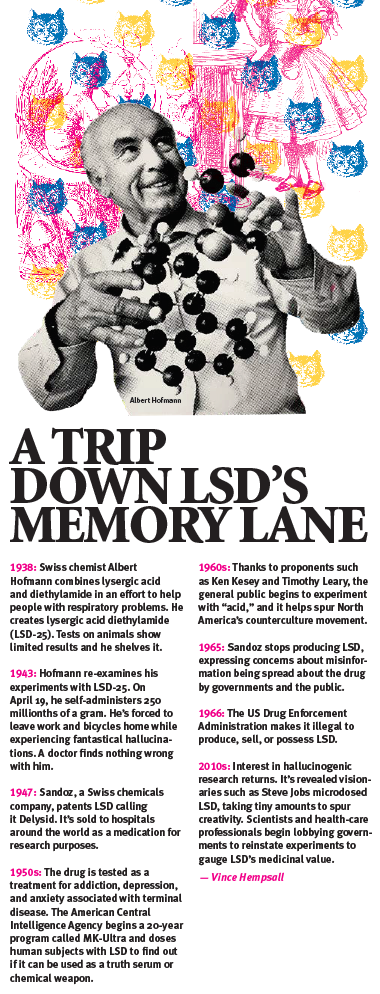

FOR MILLENIA, Indigenous Peoples have been using plants containing entheogens, which are chemicals that help produce an alternative state of consciousness. Rock art estimated to be 9,000 years old found in the Sahara Desert depicts mushroom effigies. The ancient Aztecs incorporated many hallucinogenic plants into their medicinal and social practices, as did various Amazonian tribes. It wasn’t until the 1900s that American botanist and explorer Richard Schultes introduced Western culture to a number of the plants used by native tribes around the Americas, including peyote, psilocybin mushrooms, ayahuasca, and Turbina corymbosa, a type of morning glory with indole alkaloids nearly identical to lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD).

The counterculture movement of the 1960s gobbled up these psychedelics. In response, the governments of the day made possession illegal. And it remains that way. Despite the fact Psilocybe semilanceata, commonly known as the liberty cap mushroom, grows in fields and front yards throughout the West Coast, it’s been thrust into the same legal category as heroin, and possession can carry a maximum sentence of three years in prison. Other substances in that category include coca, the plant used to make cocaine; mescaline; ibogaine; and dimethyltryptamine (DMT), the hallucinogenic tryptamine found naturally in many plants, including one of those used to make ayahuasca.

The counterculture movement of the 1960s gobbled up these psychedelics. In response, the governments of the day made possession illegal. And it remains that way. Despite the fact Psilocybe semilanceata, commonly known as the liberty cap mushroom, grows in fields and front yards throughout the West Coast, it’s been thrust into the same legal category as heroin, and possession can carry a maximum sentence of three years in prison. Other substances in that category include coca, the plant used to make cocaine; mescaline; ibogaine; and dimethyltryptamine (DMT), the hallucinogenic tryptamine found naturally in many plants, including one of those used to make ayahuasca.

But the winds of change appear to be blowing. The legalization of cannabis in Canada in 2018 could be the wedge that sees medicinal plants reintegrated into the cultural mainstream. For example, five churches in Quebec and Ontario have been granted exemptions by the federal government to import ayahuasca. Their congregations subscribe to the Santo Daime religion, which was formed in the Brazilian Amazon in the 1930s and uses ayahuasca as a sacrament of sorts in its ceremonies. According to Health Canada’s Maryse Durette, these exemptions were provided because the department was “satisfied that there are appropriate controls in place to minimize the risk of diversion and any other health risks.” A few months after marijuana became legal, a University of Toronto study was released about the increasing trend of “micro-dosing,” regularly taking tiny amounts of psilocybin and LSD. And in May 2019, Denver, Colorado, voted to decriminalize magic mushrooms. But will opposition once again try to quash the rise of medicinal plants?

Wade Davis doesn’t think so. “All those people [who opposed the use of psychedelics] are dying off or already dead,” says the famed Vancouver-based anthropologist and protegé of Richard Schultes. “We’ve watched the absurdity of the war on drugs, where the US alone has spent over a trillion dollars, and today there are more people using worse drugs in worse ways than ever before,” he continues. “The folly of the war on drugs is a lesson not lost on the people of my generation. I don’t think these substances will ever again be demonized as they were then.”

While Davis’s opinion is surely sound, it doesn’t change the fact most mind-altering plants are still illegal in Canada, which accounts for my nervousness as I sit on an orange cushion in a West Kootenay house ready to partake in my first ayahuasca ceremony. True, I’ve experimented with recreational drugs before, including hallucinogens, but I’m not a rule breaker by nature. In fact, I’m a healthy, happy person from a loving background with a supportive family who doesn’t suffer from addiction. I’m simply curious.

I’m not a religious person, but after that night I can’t help but see the world differently. I’m noticing connections I didn’t before, including those we all have to the trees and plants around us. And I now laugh at the idea of criminalizing something that grows naturally.

Many of my friends, including health-care practitioners, have done ayahuasca, either legally in places like Peru and Costa Rica or illegally in Canada and the US. Others have partaken in ceremonies using what I’m told are gentler forms of psychedelics, such as iboga, derived from an African shrub, and huachuma, which is made from the San Pedro cactus. Some had good experiences, others bad, but everyone agreed they got something out of it. “Plant medicine taught me about interbeing, the understanding that fundamentally we are not separate,” says Dr. MacKenzie from her home overlooking Kootenay Lake in Nelson, British Columbia. MacKenzie is a medical doctor, therapist, yoga instructor, and retreat organizer who believes plants hold the key to the world’s wellness. “I’m a healer and I appreciate the stakes have never been higher,” she says. “Our systems are crumbling, massive shifts are happening, and plant medicines are one of the tools helping with that.”

Before embarking on my own journey, I spoke to Constable Jason Anstey of the Nelson Police Department. He was preparing to give a talk to students about drugs, but ayahuasca wasn’t on his list; instead he’d be discussing cocaine, opioids, fentanyl, and especially methamphetamine. When asked about plant medicines specifically, he said, “I know that the derivatives of ayahuasca and iboga are still illegal in Canada, but I’ve heard there’s a lot of research into treatments using them. But it’s not really something we come across.”

Soon after that conversation, I booked my two-night local retreat for $575, and upon arrival I found myself with people from Alberta, British Columbia, and as far away as North Carolina. There was a 73-year-old widow, a professional athlete, a successful CEO, and Mike from Vancouver, who had suffered multiple car accidents in short succession and told me at one point he was close to killing himself. “Yeah, I had a plan,” he said. “You know what it’s like when you get hit in the head, how angry and confused you are? That was me times a thousand.” He credits ayahuasca for saving his life and now micro-doses psilocybin twice a week to manage his mental health.

The first night of our ceremony I drank twice within a three-hour period. A quarter shot of ayahuasca each time. I concentrated on the songs being sung, which are integral to healing ceremonies, and eventually saw interconnected, pulsating threads of light swim in front of me. Nothing I hadn’t experienced before. But after the second dose, I closed my eyes and was instantly transported to the hospital where my son was born a year earlier. I heard his first cry and felt the nurse place scissors in my hand to cut the umbilical cord. What followed next was an absolute nightmare. Every new parent fears the death of their child, and my hallucination was so dark and horrifying my entire physical being spasmed and I sobbed violently. I held his tiny body until finally the web of light returned, reached out, and absorbed us both.

The first night of our ceremony I drank twice within a three-hour period. A quarter shot of ayahuasca each time. I concentrated on the songs being sung, which are integral to healing ceremonies, and eventually saw interconnected, pulsating threads of light swim in front of me. Nothing I hadn’t experienced before. But after the second dose, I closed my eyes and was instantly transported to the hospital where my son was born a year earlier. I heard his first cry and felt the nurse place scissors in my hand to cut the umbilical cord. What followed next was an absolute nightmare. Every new parent fears the death of their child, and my hallucination was so dark and horrifying my entire physical being spasmed and I sobbed violently. I held his tiny body until finally the web of light returned, reached out, and absorbed us both.

Immediately afterward I needed to go to the bathroom, a challenge when the room’s dark and your legs are wobbly. I suffered diarrhea three times that night, which apparently is routine with ayahuasca, although typically we hear about participants vomiting. Some scientists claim it’s the excessive tannins in the potion that causes it. Others will tell you it’s your body purging bad energy. I lean toward this second theory, because after my horrific vision and subsequent purge, I felt lighter and calmer. I had faced my doubts about my son’s safety in my care, and then let them go. And judging by the retching noises around the room that night, others were also moved to let go.

The following day was spent napping and chatting. Some discussed the ceremony and I was amazed to learn a few participants hadn’t experienced much. One even fell asleep. When I hesitantly shared my vision, Mike replied that I’d undergone the equivalent of a years’ worth of therapy in one evening. We ate all morning but stopped at 1 p.m. so we had empty stomachs for the next ceremony, which started at 9 p.m. I took two larger doses of ayahuasca and enjoyed a blissful experience involving more visions of interconnected energy webs and what I can only describe as the channelling of spirits from multiple cultures. At one point, I sang a song in a language I don’t know. Another moment, I felt the presence of divine grace. I’m not a religious person, but after that night I can’t help but see the world differently. I’m noticing connections I didn’t before, including those we all have to the trees and plants around us. And I now laugh at the idea of criminalizing something that grows naturally. When I interviewed Chuck the medicine man after our first night together, I asked about his opinion on the current legal status of plants. His normally jovial disposition became serious. “Illegalities make no difference to me,” he said. “The Spanish Inquisition, the witch-burning trials, illegal cannabis: plant medicine and practitioners of it have been villainized for centuries. But we won’t go away.”

For millenia, Indigenous Peoples have been using plants containing entheogens, which are chemicals that help produce an alternative state of consciousness. Rock art estimated to be 9,000 years old found in the Sahara depicts

AYAHUASCA AND OTHER plant-based ceremonies are not without danger. Given their rise in popularity, charlatans exist, and there have been reports of negligence, molestation, and even rape at unregistered businesses in Peru and Colombia. And when you consider you’re ingesting some of the most powerful psychoactives on earth, it’s good to know who is feeding and supporting you. I looked into Chuck’s background and learned he had apprenticed with an Amazonian tribe in the jungles of Peru for 10 years and now hosts legal retreats there.

Researching ayahuasca offerings is a lot easier these days thanks to Retreat Guru. The five-year-old Nelson-based company caters to the online needs of spiritual retreats, and its website lists about 300 legal plant-medicine centres around the world. “Our business goal for 2019 is to be the number one place to book a safe ayahuasca retreat,” says co-owner Cameron Wenaus. “People need to be educated. You’re going to the jungle. You don’t know who you’re drinking with. Call the centre up and ask the tough questions that need to be asked.”

Other healers, or curanderos, I spoke to in the Kootenays warn of people who call themselves shamans. “As a bridge walker, it’s your job to move out of the way of your ego,” says Joan, a woman who apprenticed in Peru and now offers ayahuasca ceremonies around the world. “I have friends who are serving now and they should not be.” Mary, the apprentice who helped with our two-night ceremony, also has a warning. “I know people in the Kootenays who are serving different medicines each night,” she says. “They don’t know what they’re doing. They’re not going to like hearing that, but it’s true.”

Aside from personal safety, the macro pitfalls from a growing desire for plant medicines include the plundering of a finite resource and cultural appropriation. Chuck, who is North American Caucasian, says he grows his own plants in Peru. “Yeah, I’ve been accused of stealing native traditions and selling them to the West,” he says. “But the fact is, in the West we killed all our medicine people. Now the Amazon has seen fit to populate the world with us again.”

There are others who are working to ensure native cultures aren’t bulldozed. Andrea Langlois is the director of engagement at the International Centre for Ethnobotanical Education Research & Service in Spain, and she says her organization “work[s] to build bridges between traditional indigenous knowledge, community knowledge, and science.” When we connected earlier this year, she was busy helping organize the World Ayahuasca Conference, which featured over 120 speakers, including Wade Davis as the keynote.

An international ayahuasca conference? That proves plant medicines are well on their way to being mainstream, right? I doubt I’ll ever attend, but I’m satisfied I experienced ayahuasca for myself. It was terrifying and beautiful, spiritual and, well, “crappy.” I don’t believe anyone could get addicted to this drug — I mean medicine — because of the purging and nightmares involved. It’s not about a high. But in participating, I did discover a higher version of myself, one who is less afraid of parenthood and who feels more connected, who sees the world in a new way. To quote Davis, I feel like I’ve “polished my eyeballs with awe.”

*Some names have been changed to protect identities.

Vince Hempsall is the managing editor of Kootenay Mountain Culture magazine and suggests everyone might want to heed the advice he received before participating in his first ayahuasca ceremony: “Sit up straight. Breathe deeply. Open your heart. And feel the world change.”

Vince Hempsall

Vince Hempsall lives in the beautiful mountain town of Nelson, British Columbia, where he spends his time rock climbing, backcountry skiing and mountain biking (when not working). He is the editor of Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine and online editor for the Mountain Culture Group.

Related Stories

The KMC Editor Amongst Naked Sweetgrass

Last November at Kootenay Mountain Culture's Backyard Booty event, the boys at Sweetgrass released one of the most…

Letter To The Editor: What do Shooting Ranges Have To Do With Mountain Culture?

We received a letter to the editor from J.M. in Nelson, British Columbia who had some concerns about the "Amber Got Her…

CMC #17 Editor’s Intro: Here’s How To Take Back The Future

From the latest Coast Mountain Culture issue, which delves into all things futuristic, we present the editor's intro…

CMC Editor’s Intro: Wrong You Are

Most people know the Big Bang created our universe. Unless one believes humankind to be the work of Zeus, Buddha, a…