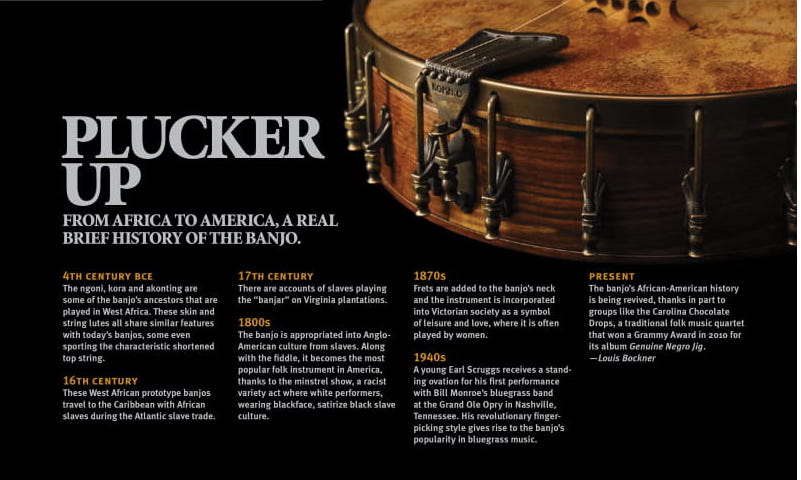

On an end-of-the-road homestead in British Columbia’s Cariboo country, a young family’s fringe existence reverberates with the twang of banjos, love and an inferno of loss. For Juno-awarding winning performers and craftspeople Pharis and Jason Romero, this is life, and the strings that are attached. Story and photos by Louis Bockner.

Located 70 kilometres east of Williams Lake, British Columbia, Horsefly is a slow-moving town. There are no traffic lights, and the thousand or so people living here are scattered across fields and forests of aspen, cottonwood, spruce and fir. The Horsefly River flows through it all, and nearby, along its willow-lined banks, a deposit of gold discovered in 1859 set off the Cariboo Gold Rush. On a warm September morning in 2017, the landscape rings of this rich, frontier-borne history, as a million golden leaves fall into cold, green water where sockeye salmon run.

To the northeast of town, down two dirt roads and a long driveway, is the home of Pharis and Jason Romero. Juno Award winners, banjo makers, parents and lovers of old-time music, the couple believes in conscious decisions, craftsmanship, good coffee and grass-fed butter. They share a love of place and tradition, of history and home, and have created a life dedicated to these values — a life where making banjos and babies share a common thread of music and melody.

For Pharis, 38, Horsefly is a place of personal heritage. She was born here, as was her great-great-grandfather, and these roots played a role in her and Jason’s decision to move back to Horsefly in 2010. To the east of their home, a creek and a small lake both bear her family name: Patenaude. In the town’s cemetery, worn headstones mark the graves of her ancestors.

ON THIS PARTICULAR MORNING, Pharis is feeding their toddler son and youngest child, Sy, in the kitchen of their new square-log home. Behind her, Jason cleans a counter while their daughter, Indigo, who is almost four, gestures grandly with a freshly cut peach.

“Knowing that my kids would be sixth-generation Horsefly, there’s a sense of place in that,” says Pharis, spooning porridge from a wooden bowl into Sy’s mouth. “It’s important, especially in this day and age where we could live anywhere.”

“I just want to be on the edge of society,” says Jason, who grew up in a small town in northern California.

This sense of place is threaded into many aspects of their lives. Their music — full of melodies steeped in old-time country and bluegrass traditions — calls back to a different era, a time when life was simpler, more grounded, authentic and tangible. Yet their life is anything but simple. Romantic? Yes, from a distance, but up close it’s busy and hectic. There are shows to practice and play, albums to write and record, and the running of a bustling banjo business.

Pharis’s voice calls to Jason from upstairs where she is dressing Sy for a morning walk. They are discussing an upcoming promotional photo shoot for their fourth album, to be released in May of 2018. The photographer will use a 4×5 film camera and Pharis is excited. “He’s got this Portra colour film that’s just beautiful,” she says. “I told him I’d send him the Escobar photo. He’s going to look into getting that contrasty black and white.”

The photo in question is a portrait of Pablo Escobar that slides briefly into view during the intro of Narcos, a Netflix TV series. Drawing inspiration from all art forms is one of many characteristics the couple shares. For Jason, 46, it’s essential to staying unique with his banjo designs. Back in the kitchen he laments the people who copy his work without giving credit. “Go to a museum. Look at something else,” he says. “Look at colours, designs. Don’t just look at other banjos. For example, I love art nouveau; we both do.”

This dedication to originality, along with a devotion to the marriage of function and form, has made their banjos coveted across North America. Six years ago, the waitlist for a Romero banjo was a year and a half. Now it’s five years. To combat this, they decided they would only open the waitlist to 25 people per year in 2014. At first it took four months to fill the 25 orders. Last year it took two minutes.

Despite the wait, customers rarely complain. “I think they understand the ethos we live and want a little piece of that,” says Pharis, while helping Sy look for toads in their newly finished greenhouse. “They want a little piece of two people living in the woods building banjos.”

“I think it’s because the banjos are awesome,” quips Jason.

“Well, that’s part of it,” she replies. “They are awesome.”

Their journey here, to a place where they’re so busy they’ve had to hire a live-in nanny, is a fateful one. They met thanks, in large part, to the banjo. A member of Pharis’s band Outlaw Social ordered one from Jason. Jason then looked Pharis up on his annual fly-fishing trip through British Columbia and, to put it mildly, they hit it off. Two months later, in October of 2007, they were married. Within a year Pharis had taken over all the inlay work in the banjo shop, and soon after, they were looking for a place to settle down. They spent nights bent over maps, knocking places off the list, many too far north, too populated, too out of the way, until the couple circled in on Horsefly.

For Pharis it meant a return to community and family, and for Jason, a move to rural life and a slower pace. “[Horsefly] has that end-of-the-road vibe,” he says, entering the workshop that sits just a few steps from the house. “I love that vibe. You’re either meant to go there or you’re lost.”

Soon they began making music more seriously together, Pharis writing songs and Jason adding critiques and melodies. Their collaboration, A Wanderer I’ll Stay, won a 2016 Juno Award for Traditional Roots Album of the Year. Things were moving.

They welcomed their second child, Sy, into the world. The foundation of a new house was poured. Their roots were beginning to grow deeper. And then, in the wee hours of a June morning in 2016, they awoke to their workshop ablaze. There was little to be done. Pharis stood naked, baby under one arm, garden hose in hand, while Jason moved melting trucks away from the inferno. Then the power went out and with it the water pump, leaving both standing helpless while everything they owned, including five newly finished banjos and all but two of their personal instruments, turned to ash.

“It would have been better if the house burned, to be honest,” says Pharis. “All our stuff was in the shop; our livelihood was in the shop.” When the ashes grew cold, people came rushing to their aid. The architect who had designed their house offered to design a new shop free of charge. Friends didn’t leave for months, and support poured in from across the globe. A stranger in Germany sent them $500 out of the blue. It offered a lesson in gratitude that they both still speak of. “No matter what, every time you turned around, someone was giving us a little piece of themselves and that’s crazy to receive,” says Pharis. “I wish for every single person, not to experience a fire but to experience the feeling of being given so much and just knowing that even if you don’t have anything to give in that moment, that’s not what matters.”

“That was a hard one for me,” recalls Jason. “How to just lay there and be gracious because that’s all you can do.” At the end of six months of construction, the family was gifted a stay on the quiet side of Maui, Hawaii, and the four of them went there to decompress. “No gigs. We just sat on the beach and ate pineapple and when we came back songs started popping out of Pharis like crazy.”

Their latest album, Sweet Old Religion, was born from the fire and the gratitude that rose from the embers: gratefulness for life and helping hands, gratefulness for home, and love for their children. It is the first album that will feature only original songs and the first recorded in their new shop.

AS THEY WORK, THE ROMEROS are cohesive, just as they are when performing on stage or watching salmon spawn with Indie and Sy in the section of Little Horsefly River that runs through their property. Pharis answers emails from customers, while Jason compares wood for banjo necks and fretboards. Birdseye maple, black walnut and Brazillian rosewood are rough cut and planed before being doused in alcohol to show the rich colours they will become. He talks to himself and to Pharis, in turn. “He doesn’t want the trim to be darker than the walnut,” Jason mutters. “I wouldn’t either,” she replies.

In the lumber room, he holds up a bag of bridges. “These are made with submerged maple from the Great Lakes. There’s science behind it, but basically it makes the best-sounding banjo bridges.”

Across the spacious shop, Pharis is thumbing through inlay materials while the voices of National Public Radio speak softly. “Mostly we do a lot of metals these days,” she says. “Copper, brass, some silver. All of the mother of pearls: gold, white, black, sea snail, lots of marquetry materials, sometimes bone and blue abalone. Pretty much anything that anybody gives me.” She is outgoing and youthful, with a slight gap between her two front teeth that softly reveals itself when she smiles. Her long, blonde hair is pulled back in a ponytail and her blue eyes twinkle when she talks.

He is more reserved. A self-proclaimed introvert, Jason sports dark hair with streaks of grey and a trimmed beard to match. To stay in shape, he jogs through the forests surrounding his property and flips skidder tires in the back field.

The shop is bright, lit by LED tubes and west-facing windows. Carpeted workbenches mark the shop of a luthier, and hand tools are neatly organized on the walls. Powermatic machines are matching beige: planer, bandsaw, belt sander, tablesaw and drill presses are scattered across the dusty floor, hinting at the insurance money they received following the fire. On the north wall sits a 12-by-36-inch green Grizzly lathe, and along the west wall a dozen labelled drawers hold pieces of hardware. Unsatisfied with the generic hardware most banjo makers use, Jason meticulously carves each new design out of maple and then ships it to a family-run jewelry shop in New Mexico where it is cast and turned into brass.

Reaching into a box, Jason pulls out handfuls of burnt metal. “Lots of bronze survived the fire because of its high melting point,” he says, fingering an ash-covered headstock overlay. Ten “From the Ashes” banjos were made from this salvaged hardware and lumber. The first banjos created in the new shop.

With childcare help, the Romeros can make three or four banjos a month, each selling for roughly US$4,500. They are works of art that come alive in the hands of a skilled player like Jason. Elegant bodies emanate a sound that defies mainstream perceptions of twanging bluegrass. To listen to their music while driving through the country that inspires it, is to understand the connection between art and place. Their songs harmonize with the murmuring waters of the Horsefly River and the whispering leaves of trembling aspen.

Despite their hectic schedule and never-ending workload, the couple is fully cognizant of its good fortune. “We’re so lucky,” says Jason, looking to the small lake where trumpeter swans will soon gather over the winter months. “We’re always aware of it. We’ll be on the dock or chasing after the kids on a perfect spring day in the back fields and we’ll know. We just try and slow it all down and suck it in.”

“We’re working hard to do less, which sounds like a complete oxymoron, but it’s true,” adds Pharis. “I’m always happy, but I’m extra happy now.”

“Me too,” continues Jason. “Now that we have kids, I really don’t need other people. I just want to sit here, stare at my children and make banjos. I just need my little family to be happy here.”

Now officially a converted banjo enthusiast, Louis Bockner loves telling stories about people who follow their passions and are unapologetically themselves. He lives in Argenta, British Columbia.

Related Stories

Why You Tour Contest

This has nothing to do with our magazine, other than the fact that we're big fans of CMH (Hans Gmoser is a Kootenay…

Octogenarians Love us Too!

Here's some great feedback from a longtime reader. Sure, she's part of the family (our Managing Editor's Grandmother),…

Eddie Hunter Shares His Love of Banff National Park and Mt. Norquay

This is an absolutely beautiful story...in an absolutely stunning place.

Why Japan Skiing is Awesome

For the past two seasons, Washington student and videographer Mattias Evangelista has skied the slopes and documented…

Why Locals Ski Naked in Golden, BC

Every summer, indecently exposed to the sun’s sizzle and with winter’s last vestige all but shrivelled up, boarders…

Why Do You Ski (or surf…or ride…or kayak…or…)?

An interesting little film here..the trailer for Lifted was released this past weekend at the Leavenworth Film…