When four ski mountaineers decided to travel 2,015 kilometres of the Coast Mountain Range, from Vancouver, British Columbia, to Skagway, Alaska, they knew the massive undertaking would take an eternity. Ten years later, the surviving expedition members are now realizing life-changing adventures don’t end when the skiing does. Award-winning Canadian Alpine Journal Editor Geoff Powter looks back at the most ambitious ski traverse ever.

Midway through a foggy morning, on July 16, 2001, a very different kind of tourist wandered into Skagway, Alaska. Two cruise ships were anchored in the deep fjord that morning, belching hundreds of typical visitors onto the tiny town’s streets, but the six men and women who walked out of the steep woods south of town that morning stood out like hookers in a nunnery. They had huge packs, looked homeless and, despite the summer season, were carrying skis. They seemed a bit lost and skittish in the big crowd, but they told a good, Alaskan-sized tale. When people asked where they came from – and people asked all day long – the happy answer, “Vancouver!” always got a laugh.

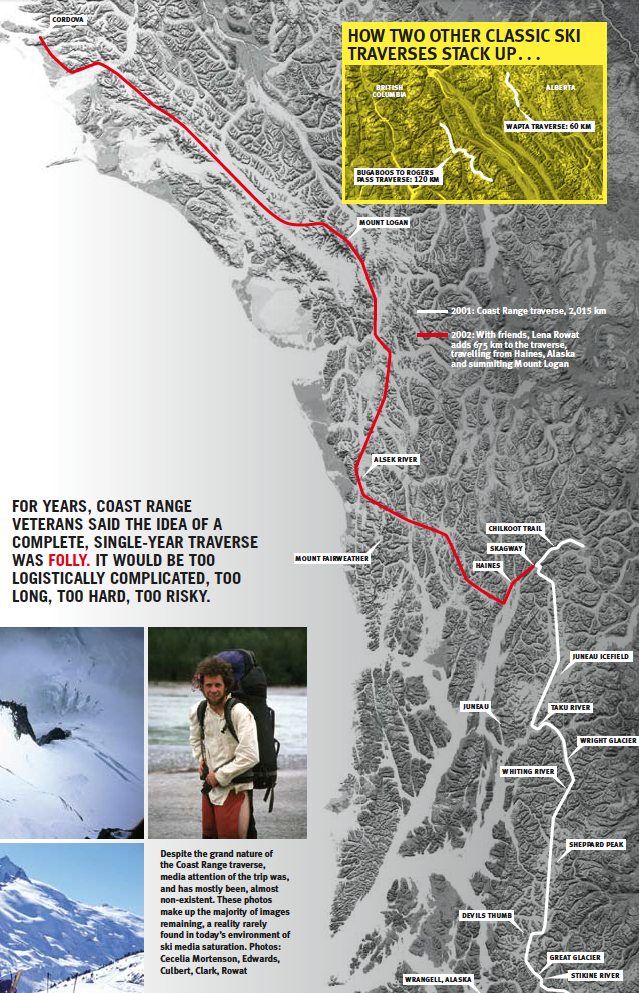

The laugh was completely understandable. Once word got out about what these skiers had actually done, even the most experienced Coast Range adventurers were left shaking their heads. Four of the six travellers (two had joined the group in the last stages of the trip), had indeed left Vancouver in February and had skied all the way to Alaska. That’s 2,015 kilometres, almost all of it in the high alpine, some of it never skied before. That’s 50 marathons back-to-back, with 20-plus Mount Everests of elevation gained and lost along the way.

[one_third]

[/one_third]

[two_third_last]

There was a lot of talk about that trip, before and after. For years, Coast Range veterans said the idea of a complete, single-year traverse was folly. It would be too logistically complicated, too long, too hard, too risky. Six months later, when it was done, the same people bowed their heads, calling it “the greatest ski ever completed, anywhere.” They said these young skiers were the next great generation, that they’d set the stage for a whole new era of exploration, and they’d “change the way people see the Coast Range.”

Ten years later, the only certainty is that no one has come close to repeating the remarkable feat, and that those six months changed the lives of the people who were there: one has barely skied since, one endured months of treatment for a broken neck he suffered halfway through the journey, two fell in love, two died, and one turned that loss into an obsession that carried her even further. when i called him this past july, Vance Culbert sounded about as far from the high peaks as he possibly could be. Culbert lives in New York City now, and while he told me stories from the trip, there were shouting voices in the background, trucks beeping as they reversed, sirens wailing. Culbert didn’t seem to notice; if anything, he explained, New York’s calmer than the places – the Middle East, Asia, Africa – where he does humanitarian aid work these days.

[/two_third_last]

I asked Culbert how he came to be on the traverse, and he laughed. “I was in Afghanistan, and I got this letter from Guy [Edwards] telling me that he’d listed me as a team member on a funding application. First I’d ever heard about it!”

Most people’s stories of the trip seem to start with Edwards. He was a superlatively talented skier and climber from Vancouver, whose star was just starting to rise a decade ago. It’s not fair to say the traverse was Edwards’ trip; there were a lot of talented, driven people on the team, but Edwards always seemed to whirl at the centre. “Fast Eddie” was a dumpster-diving, prank-pulling, evermoving dervish of energy, whose skill was matched only by his capacity for silliness. Well before leaving for Skagway, Edwards had built a reputation for happy stunts, like stripping buck naked at the base of a climb and streaking by stunned climbers at the belays. “Guy,” Culbert told me, “was everyone’s best friend. It was never hard for him to find people to do things with.”

Culbert may have been surprised to find he was a part of the traverse team but drafting him made perfect sense. Culbert had literally grown up in the Coast Range. His father, Dick, was one of the pioneers of hard climbing in the range, and Edwards knew he and Culbert both aspired to the same, noble definition of adventure: big, hard, under the radar, minimal impact and self-propelled whenever possible. That latter ambition, getting to the mountains “the right way,” as Culbert described it, before you even started to climb them, had become something of an obsession amongst him and his peers. People were walking, riding bikes, and in the case of his last big climb with Edwards, kayaking from Vancouver and then bushwhacking for miles to climb Waddington. Right from the start, that ethos was a key ingredient in the recipe for the traverse: you’d literally put a pack on your back in the city and start walking, put your skis on as soon as you could, and then just keep heading north.

“All of us had a really hard time reacclimatizing. It took months to fit back into the world.” – Vance Culbert

The others who joined the trip were also tied to Edwards and those self-propelled ideals. Dan Clark was a very strong skier who’d known Edwards from adventures together in the Rockies, and John Millar was a quiet powerhouse (“our warrior monk,” said Culbert) whose star as a climber was rising just as fast as Edwards’, though much less visibly. Millar never wrote, hardly even spoke about the impressive things he’d done in the mountains.

It was a team with enough bench strength, Culbert explained, to disregard the opinion that the traverse was “impossible.” There were, Culbert added with another laugh, “a few unique personalities on that trip.”

While the boys started a marathon of packing in the fall of 2000, (“If we could survive that,” Edwards later wrote, “we reasoned we could survive the trip.”) another unique personality was having a self-propelled adventure of her own a few thousand kilometres away. Like Culbert, Lena Rowat had literally grown up in the Coast Range, getting dragged along on multi-week adventures by a pair of eccentric parents who were convinced hardship in the wilds was a great teacher. That fall, Rowat finished a job in Florida, bought a rickety old road bike, and rode to her parents’ home in San Diego. When she finally made her way back to Vancouver, she was itching for another adventure and explains that she was “really, really bummed” when she heard the boys were well into the planning for their trip north. She was one of the rare people who’d been convinced of the traverse’s feasibility, to the point that she had been thinking for years that the real goal should not be not just getting to Alaska, as the boys were planning to do, but to continue into the Yukon, climb Canada’s highest summit, Mount Logan, and then climb back down to the sea.

[one_third]

[/one_third]

[two_third_last]

Never a shy person, Rowat phoned Edwards and asked him if she could join the trip. The two knew each other a bit, and Edwards was disappointed to have to tell Rowat they were just too far into the planning to have her join. Never a quitter, Rowat then phoned her sister Ruby and asked her to form their own team. The invitation was more than a bit of a stretch because the Rowat girls had months less time to plan than the men, and as Ruby told me, skiing to Alaska was really the first time she’d ever telemarked. In fact, she’d hardly done any skiing since she started working as a trapeze artist. But like Guy Edwards, Lena Rowat could convince anyone to do anything.

By early 2001, the impossible adventure had not one, but two teams ready to launch. The men left Vancouver on February 2, and the women just a few weeks later.

[/two_third_last]

It’s very difficult to take an adventure like this and measure it by any scale. How exactly do 2,015 kilometres and six months of hard work compare with a speed ascent of the Squamish Chief or five minutes of steep powder? When the skiers have reflected on their experience – then and now – it’s hard for them to give it any coherent, linear shape. So much happened on the trip, and yet, most days, very little. Every morning the two teams would just get up, eat, ski, eat, ski, eat, sleep. Once they got into the rhythm, if there weren’t any obvious hazards, like crevasses, cornices, whiteouts or storms, the skiers just fell into moving at their own pace, sometimes drifting far apart from each other. At times they moved far faster than their expected pace, at others they were tent-bound for days, conditions were scary, and food got stretched as thin as tempers did.

For the women, the worst moment came in a storm. They’d been whited-out for days, avalanches thundered around them everywhere, food was almost out and Lena was violently gut sick. On the edge of bailing, they finally called their father on the satellite phone.

For the men, the worst moment was much clearer. They too had been stretched by a storm, and late in a day when they rushed to make up time, Dan Clark caught an edge on a tiny patch of gravel and landed headfirst. It was a terrifying hour before the others found him. He looked bad, and he was much worse off than he looked. Clark had to be flown out. It turned out he had two severely broken cervical vertebrae. It was a miracle, the doctors said, that he hadn’t been paralyzed.

These two separate epic moments, though, ended up knitting the two teams together. When Lena Rowat called her father from her stormbound tent, he explained Edwards had called to offer her Clark’s place for the rest of the trip. All she had to do was get to Bella Coola with Ruby and then somehow get herself to Terrace, where she could join the boys for the last half of the journey. The Rowats arrived in Bella Coola 54 days after leaving Vancouver, one day faster than the men covered the same distance. The sisters hugged, and Lena hitched the long, long way around to Terrace.

A key ingredient in the recipe for the traverse: you’d literally put a pack on your back in the city and start walking, put your skis on as soon as you could, and then just keep heading north.

It could have been so easy for the addition of Rowat to be a disaster; team chemistry is alchemy at the best of times and stirring in a new person could have been terrible. Instead, everyone on the trip remembered Rowat’s presence as a welcome change. Edwards wrote that the men had gotten into a “fast and uncompromising pace” that had been creating tension, and Rowat got them to slow down and talk more before acting. The men all agreed Rowat’s habits of skiing in a flowery party dress and stripping naked to swim in glacial ponds added immensely to the scenery.

The plan, Vance Culbert told me, unfolded “exactly as we hoped.” Unusually deep snow made travel much easier than would have normally been the case. A few times over the months, friends flew in to join them: photographer Kari Medig for a leg to Terrace, Culbert’s partner Cecelia Mortenson, bringing climbing gear in for an attempt to climb the striking Alaskan peak called the Devils Thumb. The team made four unsuccessful tries at the Thumb, what Edwards later described as “the only disappointment of the entire journey.”

Six and one-half months after leaving Vancouver, joined by Culbert’s sister for the last miles, the team dropped 1,128 bone-crunching metres down to Chilkoot Inlet and stepped back into the world on the Skagway docks.

“All of us had a really hard time reacclimatizing,” admits Culbert. “It took months to fit back into the world.” Culbert went back to school, got a master’s, spent most of the next decade overseas, and not much time at all in the mountains. By the end of the trip, Lena Rowat and John Millar realized they were in love, a complicated thing for both of them, because each of them were still off on a lot of adventures, and neither had had much success before in relationships, or in Millar’s case, much experience, as Rowat was the first woman he’d ever kissed. For both Millar and Edwards, the traverse was a huge stepping stone, one that facilitated a number of other trips, including a huge new route in the Garwhal Range of the Himalaya in 2002.

For the women, the worst moment came in a storm. They’d been whited-out for days, avalanches thundered around them everywhere, food was almost out and Lena was violently gut sick. On the edge of bailing, they finally called their father on the satellite phone.

Dan Clark had his own ambitious plans put on hold by his injury. His spine had to be fused and then braced, and it was a long time before he could think of being in the mountains again, although happily, he emailed and said he couldn’t be interviewed for this article because he was just beginning a 45-day trip in Alaska with his wife and two young children.

Rowat, meanwhile, stayed focused on the plan she’d had when she first started the traverse. In 2002, she and a group of friends left the ocean at Haines, Alaska, and started skiing towards the spectacular East Ridge of Mount Logan. Forty-four days later, she summited Logan, and 11 days afterwards she was back down at the sea, adding another 675 kilometres to the traverse.

Then in spring 2003, Millar, Edwards, Lena Rowat and her father Peter went back north for another attempt on the Devils Thumb. The Rowats were going to climb the standard route to the peak, while Millar and Edwards set off up the unclimbed Northwest Face, a line that had stopped some of the very best climbers on the planet. The Rowats were blocked by weather low down on the mountain, and a long week later, it became clear that Edwards and Millar had probably been swept off the peak during the same storm and perished.

Rowat was devastated – as were a lot of people in the climbing community. But as distraught as she was, and for years afterwards, she realized the Coast Range still had some unfinished, and perhaps healing, promise for her. She wanted to be sure, she said, that she didn’t let the accident make her “give up on the mountains.” She became a midwife, a profession that brings her as much joy as the mountains do today. And when she had breaks, she went back, again and again, to complete the sections of the traverse she’d missed when she hitched around to Terrace.

In May 2009, Rowat finished the final 200-kilometre leg, this time with her father. She remains the only person who’s completed the entire 2,700 kilometres of the extraordinary traverse, an accomplishment that stands as one of the most legendary known examples of human-powered travel. Of course, you likely wouldn’t know the gravity of it from talking to her. Ten years after she, her sister and the boys stepped into their bindings near Vancouver’s city limits, Rowat still tends to summarize the trip with a disarming modesty. She humourously downplays it with understated comments like “We were just out there having fun.” However, one of mountaineering’s greatest writers and heroes, Chic Scott, has a clearer take on what the intrepid skiers accomplished. In a 2009 interview with explore magazine, he summed up the world’s most ambitious ski traverse with one short line: “It was the greatest ski, ever, by anyone.”

Related Stories

Mom & Daughter To Attempt Most Ambitious Ski Traverse Ever

Twenty-nine year old Martina Halik is either one of the bravest women we know or one of the craziest. Two weeks ago we…

Ski Your Ass Off

Winter is upon us. But as we look to the future, it's not a bad idea to drift back into the past. The glorious, super…

History of Ski Aerial Acrobatics

One of the most influential ski films of all time. Dick Barrymores documents what started freestyle skiing. From 1969…

Powder Highway Ski Bum at SWS

Chris Tatsuno has done an amazing job chronicling his Ultimate Ski Bum Powder Highway winnings. In this episode he…

Powder Highway Ultimate Ski Bum Contest

We had to post this simply because it features KMC Editor, Mitchell Scott, in his formal acting debut. The contest is…

Powder Highway Ultimate Ski Bum Vlog

We've been getting lots of requests from KMC readers as to the whereabouts and current activities of the Powder Highway…