Floods and a pandemic have exposed the fragility of our global food-supply chain. Our writer examines food insecurity and how locally sourced meat, produce, and dairy could play a critical role in stabilizing Kootenay pantries for future crises. By Jeff Lee

This story appeared in Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine #41 – Summer 2022 – The 180 Issue. For a real, hold in your hands version of the story, buy the issue HERE.

When torrential rains and heavy snows late last year wiped out every road and rail link between Vancouver and the rest of Canada, a pandemic-weary Erin Harris understood, again, just how vital her family’s fragile business is to British Columbians. Harris has always understood the challenges facing Kootenay Meadows Farm, their small organic dairy in the Creston Valley. One of only half a dozen on-farm dairies left in the province that process and distribute their own milk, Kootenay Meadows has, against many odds, carved out a business that supplies food stores throughout the Kootenays.

Four days a week, the company’s two older refrigerated trucks — laden with milk, artisanal cheeses, and products from other valley producers — head west over the Kootenay Pass to stores as far away as New Denver, Nelson, and Rossland. Eastward, it supplies the Columbia Valley as far north as Invermere. It has succeeded despite a system tipped in favour of big dairy processors and an industry governed by quotas and a managed milk supply board that requires on-farm dairy producers, like Kootenay Meadows Farm, to sell their milk to the board and then buy it back again at higher prices than it is paid under co-operative rules. The business has also faced challenges growing enough pesticide-free forage to feed its 90-head herd of robotically milked cows in such a geographically diverse landscape.

With British Columbia’s major milk-processing region of Abbotsford under water after the November 2021 flood, and with supply routes severed between Canada’s main Pacific port and stores in the rest of the province, panic buying set in. Shelves emptied and store managers struggled to find alternative supplies. Harris’s dairy normally ships out 12,000 to 13,000 litres of milk a week. It quickly pivoted, shutting down cheese-making to produce an additional 3,000 litres of bottled milk. Her dairy wasn’t the only on-farm milk processor in the province to step in and fill the gap. With central British Columbian dairies unable to ship to the Lower Mainland processors, the surplus was rerouted to Blackwell Dairy Farm in Kamloops, which went from processing 20,000 litres a week to 20,000 litres a day for markets from Kelowna to Kamloops.

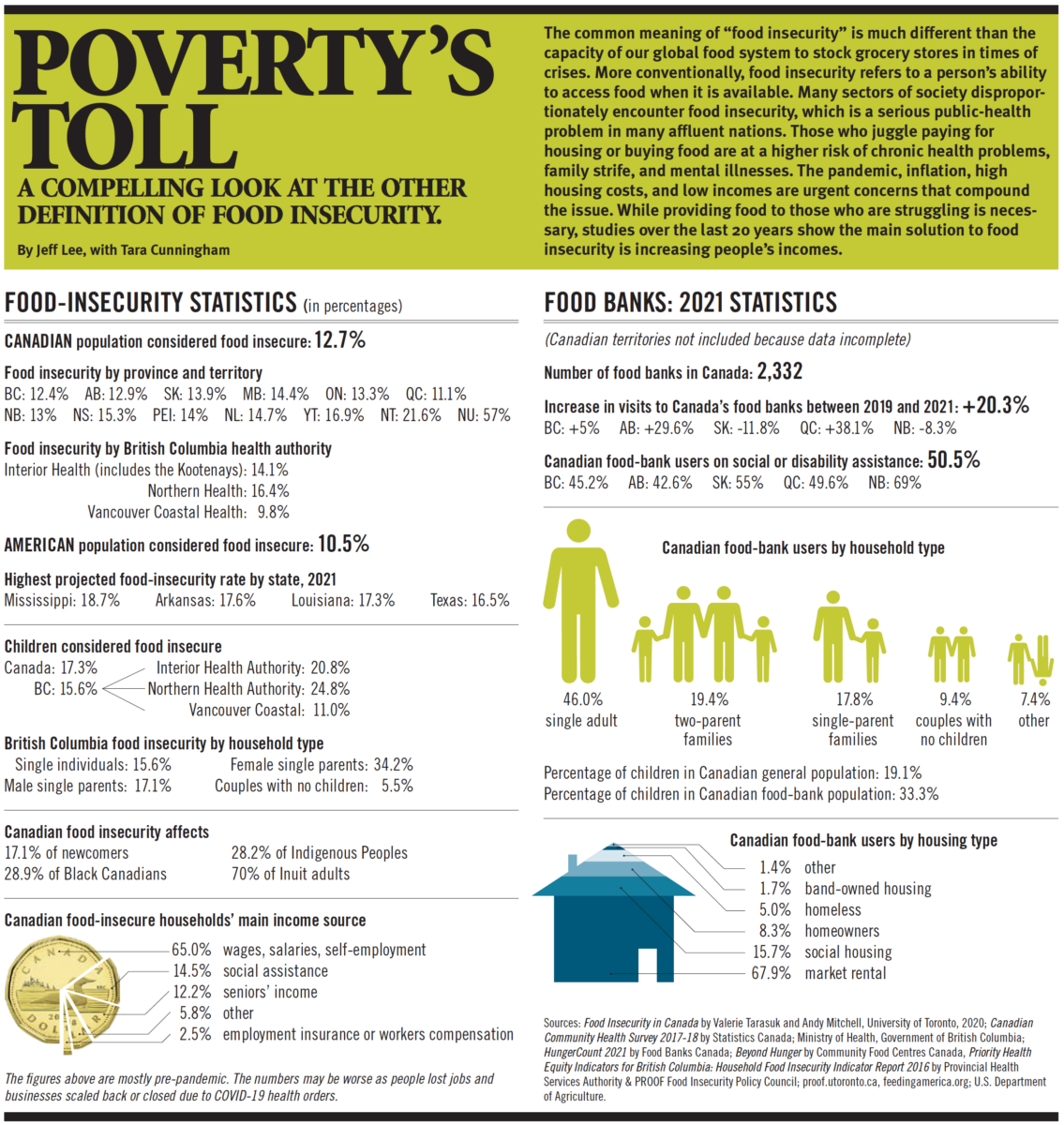

It is a reminder of the durability, and also the fragility, of local food systems. When events like this happen, the term “food security” reaches directly into the homes of people who may think they are immune. The pandemic illustrates this point: remember the panic buying of pasta and toilet paper and subsequent rationing? Even in a rich food-producing region like the Kootenays, fresh produce displays emptied everywhere. And when the floods hit, it happened all over again.

“The key point I have been making for a very long time is that we are all fundamentally food-insecure,” says Abra Brynne, executive director of the Central Kootenay Food Policy Council. “Because of the globalized food system we’ve created with long supply chains that are very vulnerable.”

Global food distribution systems built by conglomerates, subsidy programs, and offshoring cheap food production has undermined local farms. Independent abattoirs, grain processors, cold storage facilities, and other production services in communities have closed, as the farms that supplied them either downsized, went out of business, or consolidated into factory-farming operations. It is a problem Abra Brynne and many others who study the underlying issues of food insecurity saw coming decades ago. Brynne, executive director of the Central Kootenay Food Policy Council, has long argued that our food-insecurity issues are in part tied to where we now get our food. When a bag of pre-peeled carrots from Guatemala or five-to-a-bag Californian romaine lettuce can be bought at box stores for less than what local producers can ask, that’s a problem. “The key point I have been making for a very long time is that we are all fundamentally food-insecure,” she says, “because of the globalized food system we’ve created with long supply chains that are very vulnerable.”

But last year’s disruptions are only a taste of things to come. Climate change and droughts, like the sustained ones now threatening California’s growing fields, will upend long-haul food economics. “This is not a one-off, 100-year event anymore,” Brynne says. “The 100-year flood plains are irrelevant now. It is going to be every year, or every 10 years if we are lucky, but it is going to be way more often, so building in the production capabilities and the distribution and access of these essentials to the highest degree possible is necessary.”

Last year, Brynne wrote a new Central Kootenay Food Security Action Plan for the Regional District of Central Kootenay (RDCK) that took into account the pandemic, and the plan is based on three goals: ensuring people have access to healthy local food, improving “food literacy” to help access that food, and supporting local farms and producers to build capacity.

The long march of mass-producing and importing food from around the world has, in many ways, improved nutrition standards. It has given people access to a wider variety of fruits and vegetables than Canadian farmers can grow, and it has arguably reduced the price of many commodities. But it has also severely damaged the viability of Canada’s small producers and the processing system. Farmers, challenged by high input costs and lack of available labour, have found it increasingly difficult to be competitive. Family succession is also challenging; many children witness or participate in their parents’ struggle to continue farming, and often turn to other more profitable careers.

Government policy has also damaged the stability of regional food. Take meat as an example: provincial rules established in 2004 forced many small regional abattoirs to close by outlawing the on-farm slaughter of meat destined for local stores or farmers’ markets. Ostensibly done to protect consumers, the goal was to standardize inspections across the province. Instead, the rules unintentionally undermined the stability of small farms by centralizing the remaining abattoirs. Aimee Watson, chair of the RDCK, saw how these rules hurt farmers in the North Kootenay Lake area and lobbied hard to change them. Last October, after more than three years of province-wide consultations and legislative recommendations, the province rewrote its meat-slaughter regulations to create two new “farm-gate” licenses that allow small producers and ranchers to do on-farm slaughter and sell in local markets. The government also simplified and amalgamated two other licenses into an “abattoir” license that reduces red tape and creates better access.

Watson fled the Lower Mainland for the Kootenays more than 25 years ago in an act of self-preservation. A farmer and self-described food activist, she worried about her own “food sovereignty” and, like many, found a home in the Kootenays. It is a place perhaps more attuned to independence and co-operative farming practices than anywhere else in British Columbia. From the Indigenous first inhabitants — the Ktunaxa, Secwepemc, and Sinixt — to the Doukhobors who settled from Russia in the early 20th century to the American draft dodgers who settled in the 1960s and 70s, the Kootenays have a special attraction for those seeking a rural life.

Kootenay Meadows dairy normally ships out 12,000 to 13,000 litres of milk a week. It quickly pivoted after the floods, shutting down cheese-making to produce an additional 3,000 litres of bottled milk.

Watson, who settled in Kaslo, says the rural context of food insecurity is misunderstood. To her, urban residents have more access to a wider array of foods, while those in country towns and villages are at greater risk of being cut off or having fewer choices. She created the Kaslo Food Security Project as an attempt to quantify the area’s local food-production system. Her work was validated with research that showed as of 2008, the three roads leading to and from Kaslo were frequently shut down because of landslides or winter conditions, leaving the community without external food supplies for days. “In the past 23 years, the road to Nelson was closed at least once a year in 16 of those years,” says Watson. “The roads from Kaslo north through Meadow Creek and west to New Denver were closed at least once every one of those 23 years.” The outcome of her research was a guidebook, Groundswell: A Guide to Food Security for Rural Communities, on how to identify and insulate against food-insecurity issues, which she produced for rural Canadian communities.

Watson says for all its apparent benefits, the globalized food system has serious ingrained flaws. “The exchange or trade-off for that is you have a huge system that is a facade in terms of the cost of production,” she says. One of the hidden costs, in her mind, is the impact on the public healthcare system from processed foods and less wholesome methods of food production. “If you start accounting for all the inputs of factory farming, you find that [factory farming globally] is heavily subsidized. So, our health system is picking up the difference.” That bigger system, Watson believes, is the one that is most jeopardized, vulnerable to climate change and world economic shifts.

The food-insecurity issues people witnessed or experienced during the pandemic and the fall floods are profoundly different. When the pandemic hit, many small food producers, such as Harris, worried that cost-conscious people who lost their jobs would turn to cheaper alternatives. Instead, all the farmers interviewed for this article said they witnessed an upturn in the demand for locally grown foods, from milk and eggs to vegetables and meat. But when the floods hit, the impact was much more immediate. Ari Derfel, the general manager of Nelson-based grocery retailer Kootenay Co-op (also known as “the Co-op”), knew his store, like many, would empty of some basics within days. “For us, the road closures had way more of an impact than the pandemic,” he says. “It was, how do we feed this town? Conventional wisdom is that you have three to five days on your shelf at any given time. That’s a pretty scary fact.” During the floods, the Co-op, one of the largest independent grocers in the Kootenays with a reliance on organic products, found out its main supplier in the Lower Mainland could not ship. But the Co-op’s relationships with local suppliers helped keep food on the shelves. This was not a coincidence.

The Co-op has long believed that regional food security is both important and undervalued; the store offers prime space to local farmers and producers for everything from winter staples, like potatoes and rutabagas, to fresh vegetables and locally raised meats. More than once, the co-operative has withstood the interruption of global supply lines thanks to that policy.

Last year, Derfel helped a small Creston Valley meat-bird producer, Chuckureese Abattoir, obtain a supply agreement from the British Columbia Chicken Marketing Board, part of an expansion Curtis Smith had long planned for his family’s business. With the support of the Co-op, Chuckureese now produces more than 9,300 chickens, delivering 150 birds a week to the Nelson store. As one of the few chicken abattoirs in the Kootenays, it also processes another 9,000 annually for local farms and hobby farmers. “When the roads closed, we didn’t get any chickens from the Coast,” Derfel says. “We got all our chickens from Curtis.” Such relationships certainly help when emergencies take place, but they are not a replacement for a truly regional food system.

Derfel describes himself as a “food activist-entrepreneur” and believes communities have become unreasonably reliant on the global food system. But he also says communities cannot do without them either. “Generally, for people in my shoes, it would be considered sacrilegious to speak any appreciation for the large multinational industrial grocery industry,” he says. “The fact that within three or four days Save-On and Safeway could pivot and get their products from the east was an amazingly reassuring fact.”

Derfel and others, including Brynne, Watson, and Harris, believe there is a need to rebuild regional food-producing and food-processing capacity because worldwide factors will continue to make the global food-supply system vulnerable. “What we are talking about with food security and food systems is more about how you reverse the trend of taking all local food processing and production out of regions and put-ting it in a small number of factories that produce an insane amount of stuff, and instead build a balanced version,” Derfel says. “The reason you can’t compete with that scale is because capitalism has off-shored all of its production to all of these poorer parts of the world, and we are seeing in those places that as people strive for higher quality-of-life wages, those costs go up. At some point, we’re going to reach an era when there’s not going to be slaves in some other part of the planet to produce your stuff. You are going to have to de-globalize.”

British Columbia’s Minister of Agriculture Lana Popham agrees wholeheartedly with this kind of sentiment. Long a supporter of the local food movement, Popham has made efforts to strengthen and rebuild local food economies. She explains that provincial programs, such as Feed BC, Grow BC, and Buy BC, and government investments in a network of local food hubs have helped to achieve those goals. The pandemic and floods only sharpened that need. “It takes a long time to turn a system around,” Popham says. “I feel like we’ve been preparing for a disaster, but we didn’t expect all the disasters to happen in one entire year.”

Popham sees initial success in the Feed BC program, which has helped regional hospitals, colleges, and universities start to procure locally produced food. These large buyers manage scarce dollars and have tended to opt for lowest-cost imported food. But one of the first institutions to use the program was the Penticton Regional Hospital, which now sources 6,000 shelled eggs a year from British Columbia producers. “Just making a conscious choice like that didn’t change the production,” Popham says. “It didn’t really change anything that wasn’t already happening, except the way they were purchasing, which is that they were purchasing eggs from outside BC.” Initially, Feed BC’s goal was to help institutions source 30 per cent of their food from within the province. Some, like post-secondary schools, have significantly exceeded that.

At some point, we’re going to reach an era when there’s not going to be slaves in some other part of the planet to produce your stuff. You are going to have to de-globalize. — Ari Derfel, general manager, Kootenay Co-op.

Danny and Miranda Turner own Just-a-Mere Organic Farm, a fruit and vegetable farm in Creston. Danny is also the chair of the Fields Forward Society, which owns and operates the new Creston Valley Food Hub. The hub opened last year and is one of at least 12 operating in British Columbia with the support of the provincial government, specifically Popham’s ministry. From meat processing in Rock Creek to seafood processing in Port Alberni to plant-based processing in Surrey, the hubs all seek to increase local farmers’ access to local markets.

Creston’s hub, which offers processing and packaging facilities to local food producers, arose out of the society’s fruit-juicing venture. In the last three years, some of the valley’s orchardists have built new markets in the Kootenays for bag-in-a-box and glass bottled juices by using the hub’s juice press, pasteurizer, and bottling equipment. Now they’ve got their eyes on producing cherry powder from culls, soups from pump-kins and other vegetables, and more. The facility’s commercial kitchen gives space to cooks, bakers, and spice makers.

Turner is a pragmatist who understands that locally produced food does not necessarily equate to cheaper food or mean that a lot of it will stay in the area. He also doesn’t believe local producers can compete on price with conglomerates that use dollar-a-day labour in foreign countries. What is missing, he believes, is the ability to create value-added products from goods produced in the area, which the regional food hubs can help facilitate. Whether it is jugs of juice and dried fruits from cherries and apples, soups and snacks from vegetables, dried milk products from dairy, or sausages and finished meats from animals, the key is to stop being just primary producers and start processing in the region. “Finding that processing piece and putting it in the same economic district as the primary production is a path to food security,” he says. “But it will not be competitive. The juice we make at the food hub will never compete with juice coming out of California. It will be more economical [for us] and that is a step, which will then allow for the next step and the next step after that.”

There is no end of studies that delve into the problems of food insecurity. Organizations like Brynne’s; governments like Popham’s; farmers like Watson, Harris, and Smith; and food hubs like the one Turner oversees are all integral to improving local access. For Derfel, it was more than the pandemic, it was the road closures that caused him to see another step in the path toward regional food security. In the weeks after supplies started to haltingly resume, Derfel considered what the Co-op could do to help. He believes it is time for others to step into the discussion. He’s interested in the Co-op playing a role by offering seed money, along with a few like-minded organizations and investors, to create a regional social-enterprise-based processing and distribution system. As much as $1 million could be offered for a company to come up with a business plan. “We know what we have to build. It is not rocket science,” he says. “We need a plant and a production facility here. We need a net-work. We need a food hub in all the major towns in the region.” But Derfel also doesn’t believe such local enterprises can move the food security dial alone. “There isn’t the economic capacity with any of those single organizations to do the really large-scale stuff, so, you need regional pooled thinking from an economic-development standpoint to support all this stuff.”

Harris, the dairy farmer, ponders the impact of what Derfel, Turner, Watson, and Brynne believe needs to happen. “Consumers see embodied value in products now that they didn’t see before,” she says. Due to COVID, “more people are committing more of their money to good local food because they see value in how local is produced. We need to collaborate and produce and process more locally, but it will take more than individual farmers. It will take a collective conscience to do that.”

About the Author: Jeff Lee is a co-owner of a commercial beekeeping business based in Creston, British Columbia. After 40 years writing for news-papers, including the Vancouver Sun, he describes himself as a recovering journalist. He’s a board member of the Creston-based Fields Forward Society.

Related Stories

The Kootenay’s Own Youth Climate Corps Helping Curb Wildfire Threat And More

"The climate is changing and so are we." Kootenay youth band together to help bring down emissions and build…

Burton Has Thrown Down the Gauntlet. Environment Will Win.

Burton just announced huge sustainability goals it's committed to achieving by 2020. We spoke with the company's VP of…