With the world all a-Twitter over anything shareable, those hired to sell British Columbia’s adventure-tourism products using brochures and mountain-media advertorials now have to understand impressions, likes and smartphones. But online efforts by the mountain-bike marketeers of Golden and Squamish beg the question: are metrics making money or simply offering cheap clicks?

Beads of sweat drop to the forest floor as Brady Starr and Evan Fishlock swing pulaskis into the tough, rocky ground above the Columbia River. They’re uncovering new-age gold — a commodity that doesn’t trade on the stock market but rather in the infinitely expanding sphere of digital influence. Their precious resource is trail: a giant spiderweb of flowing, perfectly packed dirt that weaves its way through pine and spruce, delivering — but perhaps more importantly, attracting — riders into the burgeoning tourism economy of Golden, British Columbia.

Starr’s company has been contracted by the Golden Cycling Club to expand the Moonraker network of trails, which is an old cross-country system that’s had new life breathed into it in recent years. No longer are these kinds of networks the esoteric secret property of local rogues; they’re a community asset deliberately designed to suit a wide range of riders — and there are now more riders than ever. The International Mountain Bike Association estimates the number of North American mountain bikers at 40 million and growing.

But getting those riders onto the trails in your particular town is what counts. The fact is, mountain biking is now an important economic driver for summer tourism across North America, but vying for that market as a small community, like Golden, is no simple task. For one, it’s competitive. As digital culture and social media change the rules daily, communities need their marketing to be shrewd in fighting for attention and have an insightful grasp of a field forever in flux. The consumer isn’t just the subject anymore but also an agent. And a very powerful one at that.

Leading the content-sharing charge are Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, who represent a direct, highly influential line that starts from the authenticity of a rider’s experience, straight through to trail societies, district marketing organizations and tourism boards. As such, it’s hard to tell who’s pulling whose strings these days. The digital world provides an instantaneous feedback loop with ever-changing input and output points. What’s most difficult isn’t necessarily setting the trend, but staying on it.

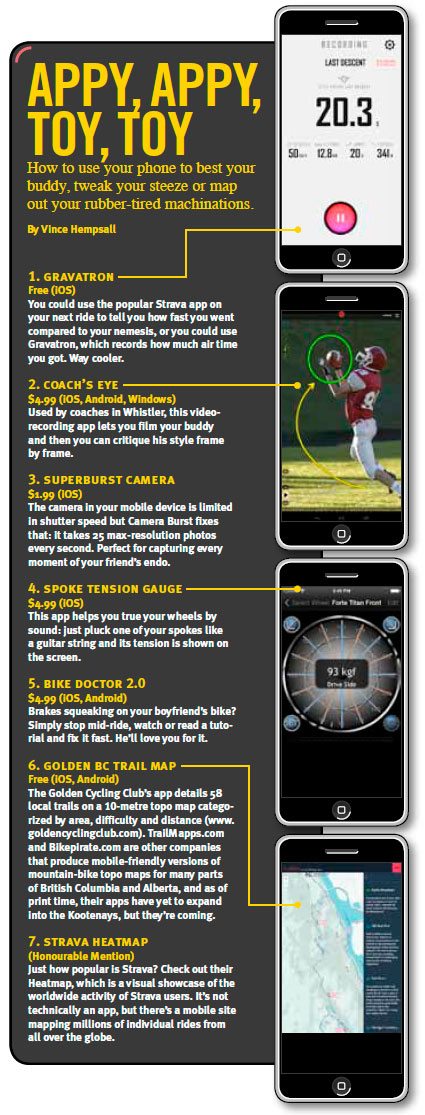

Apps like strava — which uses GPS points from your smartphone to map and record your ride time and then posts it to facebook — are an example of how personal digital bragging now inadvertently markets the community at large.

For Golden, the big picture is that community-owned bike trails are good for business. The town is one of 14 resort municipalities in British Columbia, which means there’s a two per cent levy on all hotel rooms that goes directly back into tourism infrastructure and marketing. As Tourism Golden’s Joanne Sweeting explains, “Ideally if you spend 10 per cent more on marketing, you want to see a subsequent return in funding because it’s the result of extra visitation.”

In the new digital world, though, measuring growth is done with data extracted from “metrics.” Tools like Hootsuite and Facebook Analytics provide businesses with up-to-the-second marketing information about their online interactions. The catch-all term for views of content is “impressions.” Out in the physical world, you have to survey people to ascertain your marketing reach, as in: who saw your billboard or acted on a print ad? Though the immediacy of data online is a boon, the trick right now is that there is, well, no trick. There is no magic formula that correlates data from social metrics directly with revenue. This quicksand is known as ROI: return on investment.

The digital world provides an instantaneous feedback loop with ever-changing input and output points. What’s most difficult isn’t necessarily setting the trend, but staying on it.

Lars Lofgren is manager of growth at San Fancisco-based KISSmetrics, a prominent online marketing firm that specializes in digital strategies. As Lofgren puts it on their blog, “The end goal is actions, not eyeballs.” He also calls potentially distracting data “vanity metrics.” In other words, growth of impressions alone isn’t necessarily an accurate reflection of ROI, especially if it’s not helping you make decisions.

Andy Brown is Tourism Golden’s social-media coordinator, and when asked how he knows growth online equals growth to the bottom line, he says, “Faith would be one way of putting it . . . . It’s difficult to measure, but it’s widely accepted that it’s very influential.”

[divider margintop=”20″]

[one_half]

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

[divider margintop=”20″]

Three hundred kilometres away in Calgary, Chris Turner of Calgary Cycles confirms that digital word of mouth is the biggest way his customers hear about new trails. “Everyone is more interconnected. If someone sees that picture of [Revelstoke’s] Frisbee Ridge, then they want to go,” he says. “Or, say, it’s gone around your whole friend circle that Fernie has a new trail, then everybody knows about it.”

Turner says he’s hearing more and more about Golden, but Fernie and Revelstoke are still top of mind for his customers. However, trumping all three, what he’s most excited about right now is the new map app for Squamish, British Columbia, the longtime mountain-bike hotspot just north of Vancouver. The app allows a user to peruse, in detail, all the sanctioned riding in Squamish from his or her phone. This underscores the biggest challenge of the digital landscape: you’re in competition with everybody, no matter how far away or the size of their marketing pockets.

Squamish lauds itself as the outdoor recreation capital of Canada, and that might be right in terms of mountain biking, according to Brady Starr. “It all comes down to the Squamish Off Road Cycling Association (SORCA),” he says. “When they got the money to build [the trail Full Nelson] by partnering with Anthill Films and Red Bull, the town really grabbed it by the horns and promoted it. That became a model for other communities.” For those not in the know, Full Nelson is basically a pedal-accessed version of Whistler’s A-Line — a gold rush of a trail that sets the bar for what community-driven singletrack assets can look like without having to visit a resort.

Today, Tourism Squamish is investing more in social media and alternative forms of marketing, and they no longer buy traditional advertising. They do, however, plan to use their resources at the Squamish Adventure Centre to launch a pilot project that will further extract data on where people who visit Squamish get their information.

[/one_half_last]

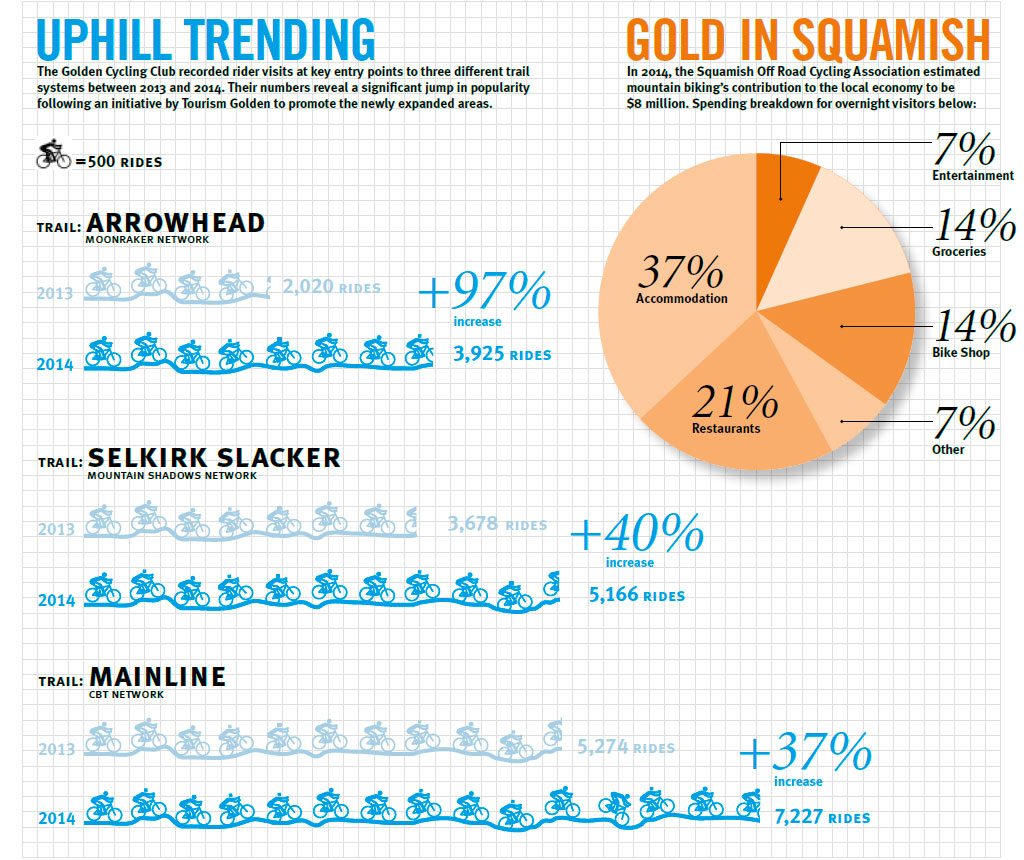

SORCA already has some impressive stats to share. For their 2014 Economic Impact of Mountain Biking in Squamish study they used automated trail counters and interviews to determine that 75 per cent of riders in Squamish are visitors, of which 40 per cent stay over for an average of two and a half nights. This represents an estimated $8 million in direct spending for a single bike season.

Bruce Pomeroy of SORCA explains that all initiatives need not be totally coordinated to be mutually beneficial. “If there’s some maintenance or a new trail that SORCA’s funded, we’ll put that news out to our membership through our Facebook page. It’s not our mandate to promote beyond that, but it’ll naturally spread from there.”

The unveiling of the trail named Rupert this past summer in Squamish was a prime example of SORCA’s influence and reach; it enjoyed incredible popularity almost as quickly as it opened.

Back in golden, Golden Cycling Club President Chad Gennings says, “As the number of trail users increases, so does the likelihood that local government and businesses will be willing to provide financial support for the trails.” Hence, more riders means more riding — for everybody. But for a town of 3,700 people, that means you have to draw riders from out of town, too.

Andy Brown agrees. “There’s no direct social-media strategy between the Golden Cycling Club and Tourism Golden,” he says, “but we promote the cycling club as much as the trails because they’re the lifeline to the trails.” In turn, part of Brown’s job is to enable the digital reach of club members and other advocates by sourcing and introducing content into the social-media channels they use — giving them something to share, fuel for the fire.

Apps like Strava — which uses GPS points from your smartphone to map and record your ride time and then post it to Facebook — are an example of how personal digital bragging now inadvertently markets the community at large.[divider margintop=”20″]

These numbers are an approximation based on sensors positioned along trails for four months in 2013 and six months in 2014. A monthly average was created based on total numbers and then multiplied by six to create a relevant comparison between the two seasons.

[divider margintop=”20″]

To put this into perspective: Tourism Golden has 1,147 Twitter followers and 4,474 Facebook fans. That’s how many individual feeds they reach with a single post. If each of the GCC’s 300 members shares content Brown posts, once, and they have an average of 300 friends themselves, that’s a potential reach of 900,000 people.

Here, content is the gas that makes the machine run: video, photos, words, music. But quality forms of content aren’t free, so it’s increasingly being produced specifically for the viewing and sharing patterns of social media itself.

As such, one of Tourism Golden’s campaigns last summer enlisted local athlete Shane Kroeger to provide blog posts, photos, helmet-cam footage and Strava logs during the Totally Spoked bike festival: a series of four independent events that took place over 12 days between July and August. Tourism Golden then populated social media with as much content showcasing the trails as possible. Amongst this was the announcement that the athletes on the Single Track Six tour voted Golden’s trails their favourite on the tour. During that campaign, Tourism Golden’s weekly growth in followers jumped by 20 per cent.

The Golden Cycling Club has even just released a free map app on their website that provides advanced riding data of all sanctioned trails — four full networks. Rumours are also circulating online about an upcoming climbing trail on Mount Seven, and three “section 57s” are under consideration for alpine zones — that is to say, the right of way for a trail.

It’s hard to know for certain if the digital inputs directly result in positive real-world outcomes, but there’s certainly no lack of effort in this corner of the East Kootenay. In the words of Andy Brown, “As long as things are trending up, you know you’re doing a good job.” In Golden, where the online community quadrupled and ridership grew nearly 35 per cent from 2013 to 2014, things are trending up. Way up.

Matt Coté

Matt is the associate editor at Forecast. He's been penning and editing ski, adventure and mountain culture-based stories for over a dozen publications for the last decade.

Related Stories

Golden Sound Festival Recap

Festival season is almost at a close across the Kootenays, but the sweet sounds of summer are still ringing between our…

Golden Sound Festival – August 19 & 20

If you're in the East Kootenays this weekend be sure to check out the Golden Sound Festival, scheduled to go off August…

The Science of Sport 2: Mystery Machine

[divider] A collection of essays from Coast Mountain Culture’s writers that explores how science supports our bodies as…