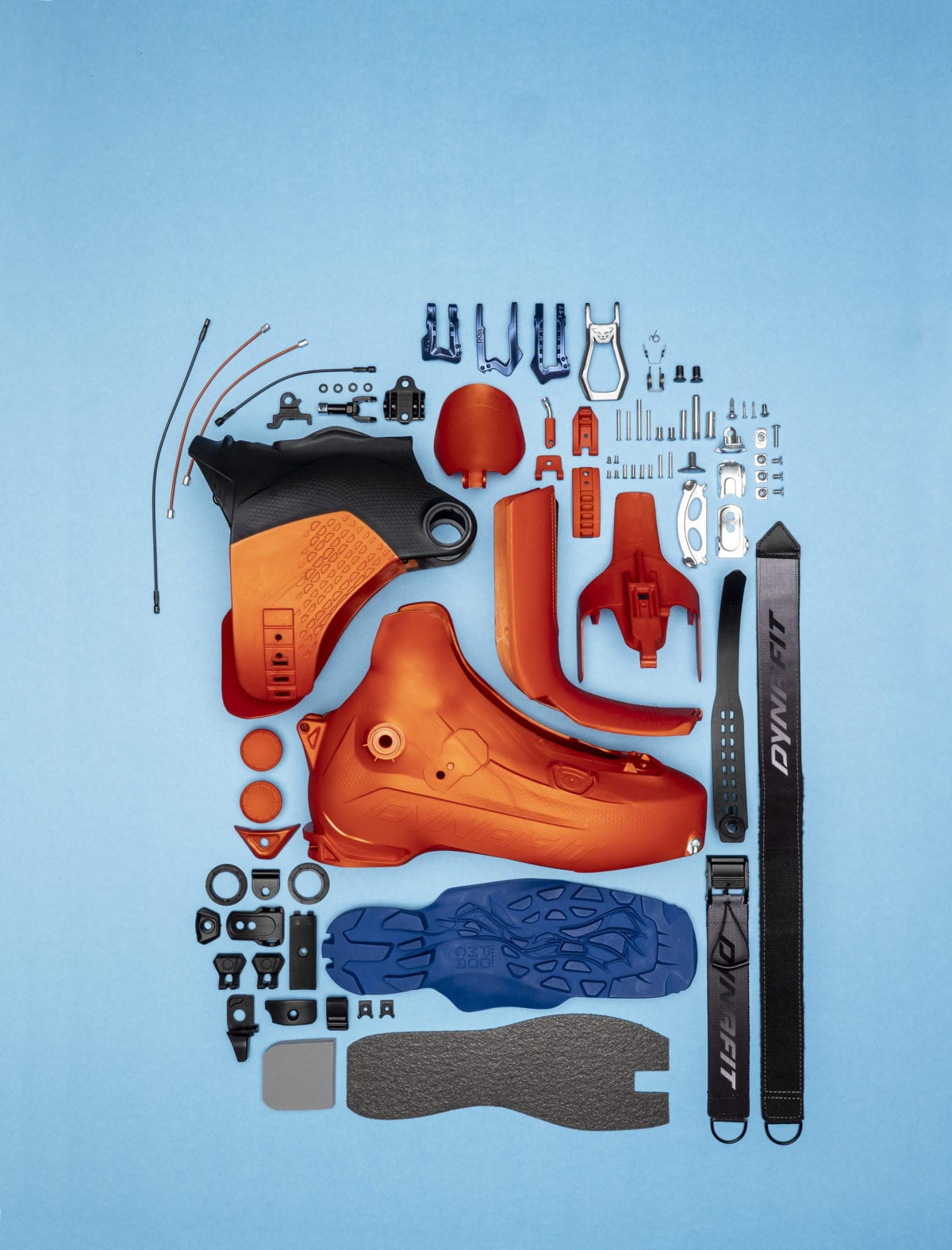

Market demand and corporate consciousness have placed the manufacturing practices of many outdoor brands at a crossroads. Some companies that make your new jacket, gloves, and shoes have shifted toward more sustainability, but the builders of boards and bikes have larger challenges. For those hard-goods makers, the ride has just begun. This is a sneak peak of the story by Ryan Stuart. The full article can be found in the latest Kootenay Mountain Culture magazine out now.

My job is sustainability’s worst nightmare. Along with writing articles like this one, I review outdoor gear for magazines and websites. Companies send me their latest and greatest. I test the gear, which means going mountain biking, hiking, paddling, climbing, and skiing, and then write a review. I’m always riding a new high-end bike. My ski rack is full of next year’s models. If Imelda Marcos hiked or ran, she would drool at my shoe collection. I have a jacket for every possible situation. It’s awesome fun, but also terrible. Just about every time I tap out a review, I’m telling every reader that they should trade in whatever jacket, ski, or bike they own because this one is better. I encourage consumption and that’s the antithesis of sustainability, the idea of having the least impact on the planet, while improving people’s lives.

At least these days I can steer readers toward better choices. For the last decade sustainability has been a growing topic and focus in the outdoor gear industry. Mostly on the soft-goods side: think outerwear, layering tops and bottoms, sleeping bags, and the like. Brands talk about the steps they are taking to make sure working conditions are safe and wages fair, about the work-life balance of their employees, about shifting from carbon-heavy processes and energy sources to more efficient ones, about using recycled and organic raw materials, about advocating for and donating money to the environment, with third-party certification and audits speaking to these efforts. Sure, some of these endeavours are marketing hot air, but most of them are legitimate.

The study compared a carbon-fibre Roubaix road-bike frame to a comparable aluminum model. Because water is used throughout the production and lay-up process—in resins, chemical washes, cooling, cleaning, and more—it’s a water-intensive material to make: it consumes an astonishing 2,300 litres per frame. That’s about what one human needs to survive for a year.

On the other side of the store, where you find the hard goods, like skis, snowboards, bikes, and tents, the conversation is mostly crickets. Only a few ski brands, and none of the big players, mention sustainability efforts. Researching this article, I struggled to find a bike brand working to reduce its environmental impact. The challenges are greater on this side of the industry, but still, companies should be doing the work to make their products more sustainable.

We consumers are just as bad. Most of us seem to be in denial that the gear we use for recreation has an impact on the environment. Raw materials are full of chemicals, and manufacturing is energy intensive and uses massive amounts of water. Every year people like me tell you to go buy something new. At the end of its life, that gear gets thrown in the landfill. “As people that choose to enjoy the outdoors and prefer human power to four-stroke recreation, we think we’re really green,” says Brian LaPlante, an outdoor industry veteran. “We compost. We recycle. We ride to work. But we don’t think about the impact the gear we buy has on the world.” But things are changing. A growing list of companies and associations are working to help us make more sustainable choices. Nowhere is that more needed than in the ski and snowboard industry.

To read this article in its entirety, pick up the latest issue of Kootenay Mountain Culture magazine out now. Or watch the site in the coming weeks as we upload more.

Ryan Stuart

Ryan Stuart has been fascinated by the natural world since he was a kid, and he’s now sharing this interest through his freelance writing, which he does from Comox on Vancouver Island, British Columbia.

Related Stories

KMC Mentioned in The New Yorker Magazine

Well hey, you could say we're flirting with the big time here. I spent some time at the Olympics with a friend and…

KMC Sponsors Upcoming Vertfest 2015

Vertfest is returning to Alpental on February 14 and 15, 2015 and, once again, our sister title Coast Mountain Culture…

The KMC Editor Amongst Naked Sweetgrass

Last November at Kootenay Mountain Culture's Backyard Booty event, the boys at Sweetgrass released one of the most…