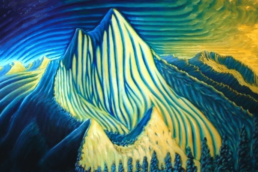

Ten years before Lewis and Clark crossed the continent, Alexander Mackenzie reached the Pacific Ocean through British Columbia’s Peace River area – now being threatened by the Site C Dam. A new book excerpt tells how it was a journey ironically assisted, and foretold, by First Nations who preceded him by millennia. By Christopher Pollon.

Just downstream of the confluence of northern British Columbia’s Halfway and Peace Rivers, in the protected shallows of a long island hugging the mainland, photographer Ben Nelms has encountered an astonishing sight. At twilight, in the midst of a thick hatch of mayflies, he watches as at least 20 fish break the surface at any given second. It goes on for minutes.

All my life I have read and listened to forlorn tales, tinged with awe and regret, of the loss of areas of great natural abundance in Canada. Like, Vancouver Island rivers running so thick with coho salmon that pioneers had to walk over their backs to ford a stream, or, Newfoundlanders collecting great drafts of cod by simply tossing buckets into the sea. For Ben and me, this is one of those moments.

We’re conscious, too, that we are mesmerized by this twilight feeding frenzy, we have fallen victim to “shifting-baseline syndrome”: what to our eyes in the autumn of 2015 is wondrous abundance, surely must be a sad fraction of what once thrived here. Rare moments like this make us imagine what wonders Alexander Mackenzie, the first European to explore the northeastern corner of what became BC, must have witnessed in the 1790s as he paddled this same stretch of river. His journals, which were bestsellers in his day (Napoleon Bonaparte had a volume translated into French to bring with him in exile on the isle of Saint Helena), provide some idea:

“Mr. Mackay, and one of the young men, killed two elks, and mortally wounded a buffalo… The country is so crowded with animals as to have the appearance, in some places, of a stall-yard.”

It is believed that Mackenzie was referring to a spot close to present-day Bear Flats, near Fort St. John. At the time that journal entry was written, he had recently left what is now Alberta on his way to the Pacific Ocean, travelling westward along the Peace River, through the break in the Rockies.

The Peace region at that point was the northern limit for the now-extinct American passenger pigeon, which was once so numerous that their migrations could impose darkness on a clear day for hours on end. As Mackenzie noted during his 1793 travels, buffalo still roamed the region, and he reported seeing them as far west as the Parsnip River—not far from the current location of Mackenzie, BC. The buffalo he saw (and ate) were descendants of a much larger species of bison that first migrated into North America from Asia about 200,000 years ago, using the Bering land bridge connecting Siberia to Alaska. Buffalo bones more than 10,000 years old have been found at Charlie Lake Cave, just north of Fort St. John, bearing the marks of stone tools handled by the early hunters who feasted at the site. It’s possible that these humans, whom archeologists suspect emigrated from the south, lived among woolly mammoths, horses (slightly smaller in size than the modern horses we know), muskoxen and a species of camel resembling a modern dromedary. (Horses and camels were both native North American species—they migrated to Asia using the Bering land bridge.)

By Mackenzie’s time, the great herds of buffalo were concentrated from central Alberta into neighbouring, south-central Saskatchewan and down into the US, from Montana to Colorado. While these enormous herds did not exist in the Peace region, the large quantity of buffalo bones found at nearby Rocky Mountain Fort demonstrate that these animals were an important staple used to provision BC’s early fur trade. The last buffalo in the region was reportedly shot dead in 1906, near Fort St. John.

The arrival of Mackenzie, by canoe along the Peace River in 1793, was not a complete surprise to the local First Nations. It is said that the appearance of white men and the fur trade had been foretold by a powerful Beaver (Dunne-za) First Nation prophet, a visionary named Makenunatane. Dreamers of great power were known as swans, because it was said their souls could fly. Swan Chief Makenunatane saw maps in his dreams as real as anything on paper, depicting the converging pathways of animals, humans and the spirit world. The Prophecy of the Swan, a book about the early, upper Peace River fur trade, reports that the arrival of the white man saw the people look to Makenunatane for direction. He counselled that they should embrace the fur trade and Christianity, and he personally transitioned from a chief of the hunt to a chief of trade.

For his part, Mackenzie would go on to brave the Peace Canyon—where, facing a near mutiny from his crew, he was forced to portage around it. He would become the first European to cross the North American continent to the Pacific Ocean, beating Lewis and Clark by more than a decade. The feat had a little-known anti-climax: in order to reach the coast, Mackenzie had to abandon his canoe and hike for two weeks, and then borrow a canoe from local Aboriginals for the home stretch.

Without the charity of First Nations, one of North America’s greatest explorers, whose wanderings opened the Peace region to the fur trade, would have never touched Pacific tidewaters.

An excerpt from The Peace in Peril: The Real Cost of the Site C Dam (Harbour Publishing), by Christopher Pollon, with photographs by Ben Nelms.

Related Stories

Real News? This is Why Mountain Towns Are Only Getting Half The Story

Sweeping monopolization, unprecedented newsroom cuts, and the internet have done great harm to local journalism. Resort…

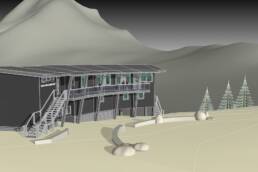

Construction Begins on First Spearhead Traverse Hut

Earlier this year we reported that permission had been granted and funding received so huts could be built on the…