We live in a country that was built upon the fur trade. And even though it no longer retains the same commercial importance, it’s still a lifestyle worth pursuing for many rural British Columbians. In the snowbound woods of the Kootenays, Emily Nilsen meets trappers old and young who play the ancient scent game. Photographs by Kari Medig

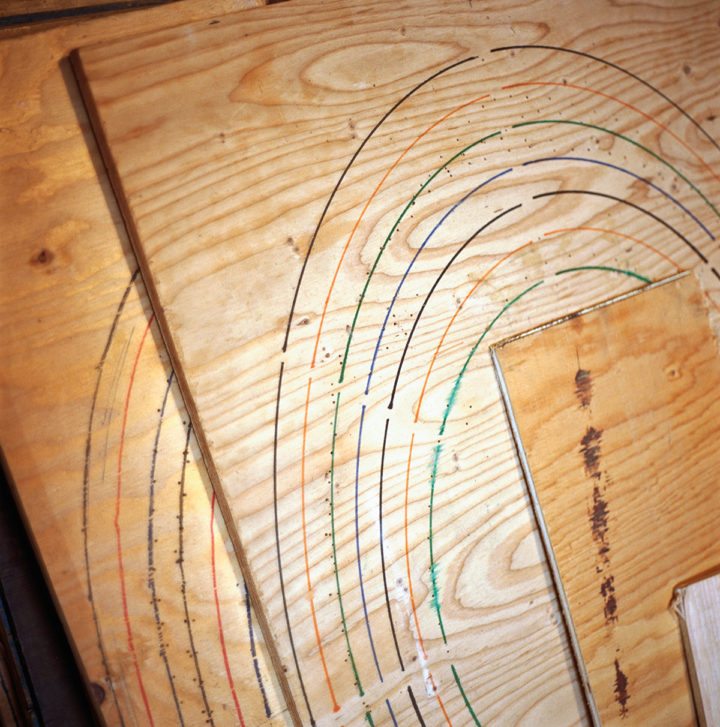

“Snip here. Grab your tail stripper. Pull. Scrub it down.” At the 64th annual BC Trappers Convention in Cranbrook, a man wearing a rubber apron and providing play-by-play over a headset is making skinning a raccoon look surprisingly easy. He clips around the feet and daintily pulls the animal hide away from its body, as though removing a satin glove. Similar demonstrations are under way throughout the hall. Muskrat, coyote and fox furs dangle on hooks while onlookers huddle attentively on bleachers. Beaver pelts are stretched round as plates onto plywood boards.

Trappers tend to be stereotyped as hermits by the very nature of their remote trade. In 1926, Canada was split into a puzzle board of trapline tenures on Crown land: 2,600 in British Columbia, 250 of which are located in the Kootenay region, and approximately half of those are owned by First Nations. Get-togethers like this convention offer a rare opportunity to share tips and traps, pelts and prizes. With only 1,400 licensed trappers across British Columbia, the need for collective merriment coaxes even the most reclusive characters out of the woodwork.

Because most are mechanics or dentists by weekday and trappers by weekend, many view trapping as a recreation. But there is no consensus. “I prefer small business,” one says indignantly, pointing out that his income from selling pelts — $3,500 a year — allows him to write off his expenses. Meanwhile, modern trappers can sit in their living room and watch live-stream fur auctions taking place in Prince George, while elsewhere the internet buzzes with trapline blogs, instructional YouTube videos and online discussion boards.

A middle-aged woman leans across a pelt-laden table. “There’s a banquet and a dance later,” she invites, clasping a bundle of hot-pink rabbit furs. Behind her, a slideshow draws a crowd, wildlife images caught by a trail camera. The creatures gaze back, dazed by the flash, peering from the screen into a sea of coonskin caps, camouflage, and plates piled with prime rib and salmon steaks.

“You guys must be the granola from Nelson. You’re late.” Mannie Roberts, president of the East Kootenay Trappers Association, calls out from a corner booth in a Cranbrook Arby’s. It was Roberts’ trail camera that digitally captured the animals.

Finding an in with the trapping community was not easy. Trappers can act squirrelly and even mafiaesque, hesitant to share information. But despite initial intimidations — one of which jokingly warned of an open season on humans — Roberts opens up. Holding a mug of green tea between his large, rough-trodden hands, he talks about his Elk Valley upbringing. “We were really poor people,” he says. “Us four kids rode in the boxcars like hobos, with a few dynamite boxes full of our junk.”

It’s a common story among the over-70 set, whose intimate connection to the land was often sourced in a family’s need to survive. “I got my start out in the bush, and I’ve never been very far away from it,” Roberts says. “What I shot we ate. If it hadn’t been for wild game, we would have starved to death.”

These days it’s tricky for Roberts to get onto his trapline. The perils of long days alone on the line are more apparent as he ages. It stings him to not be able to jet around like he used to, though he still has a reason to go. “Some of the best times I’ve had with my son have been on that trapline. Before we go to sleep at the cabin, he always wants to hear about the old days.” Roberts will happily oblige. “I was raised with gas lanterns and cooking on a woodstove. That’s how it is on the trapline,” he sighs. “But a lot has been lost. Eventually it all might be lost. Most kids are more excited about Nintendo than being in the forest.”

Sitting in a fast-food joint next to a belching highway, the forest seems far away, a swath of green disappearing, reforming into broken pieces of land. Roberts recognizes many modern urbanites may not understand or approve of his way of life. This is often an understatement. Trapping is not a black-and-white subject: it is a solid lump of grey.

Outside the trapper circle, opinions run the gamut from disdain to indifference, peppered with the occasional, “People still trap?” As one young farmer who traps mink to keep them from feasting on his chickens puts it, “Nothing has inspired more human guilt in me than killing smart, independent creatures with steel tricks.”

Neither is formal opposition uncommon. Author Luanne Armstrong, who has written extensively about place and had her own rural upbringing in Boswell on Kootenay Lake, is adamant. “The destruction of large numbers of animals purely for consumer purposes is not justified.” When asked about the deep connection to the land that many trappers seem to posses, Armstrong says, “It’s not the knowledge and love that are important but the ultimate purpose and end result. People ‘love’ all sorts of things. ‘Loving’ an activity doesn’t necessarily make it ethical.”

But Roberts has a different perspective. Step out of the city and predator-prey relationships define what it is to be a wild animal. “I’ve watched wolves feed on fawns just coming out the birth canal. Stuff that will curl your damn hair,” Roberts says. “Anything we do is better than what nature does.”

Bobby Faiers is an East Kootenay trapper with an exemplary knowledge and love for trapping. While attaching feathers to a crossbow arrow behind the counter of his store, True Flight Archery, he talks about electronically tracking cougars and wolves for research. A Google map open on his desktop shows red lines slinking around Cranbrook and up towards Kimberley. The cougar line zigzags over the same spot for several days. “Probably has a deer there,” Faiers reckons.

The next day, Faiers brings his wife, nephew, and two great-nephews onto the trapline. It’s a grey day and the clouds are thick with snow. When he learns that highway workers left a road-killed elk nearby for him to use as trapline bait, he sleds off to pick it up, only to return empty-handed. “Cougar got to it first,” he yells over the idling engine.

Two sets of paw prints circle around the carcass, one large and one small. Faiers drags it off the road, leaving the cougar and her kitten to feed in peace. Death provides nourishment elsewhere. Scavengers scrounge the forest floor, birds flutter to feast, the soil is eventually enriched by decay.

Many trappers pride themselves in playing a role in this process, for example, by leaving beaver meat high in a tree to feed female marten through gestation, or returning unused carcasses to the woods. The animal’s life, and death, disappear in a matter of days as nature picks away at the remains.

Heading up the logging road into the patchy forest, Faiers pauses to watch a pair of moose wander through a small cutblock. He calls out with a nasal, guttural snort. They wander away, long legs paddling clumsy strokes through the snow.

There are several cabins on this line. One was recently set on fire, which hurts. Faiers’ wife stops at the other cabin, warming it up for lunch. The oldest nephew begs to keep checking the line, rather than continue jumping from the cabin roof into a crusty snow bank. “If there are any animals, we’ll come get you,” Faiers assures him.

“I was raised with gas lanterns and cooking on a woodstove. That’s how it is on the trapline, But a lot has been lost. Eventually it all might be lost. Most kids are more excited about Nintendo than being in the forest.” — Mannie Roberts, Cranbrook

Back on his sled, Faiers wordlessly scopes for lynx or wolf tracks. To be “successful,” a trapper needs to imagine or observe animal thoroughfares to know where to place the trap, the knack for which Faiers is considered one of the best. His trapline has been in the family since the 1930s, and his knowledge of this land fans out like a grouse tail.

There is a German word used to describe other species’ subjective experiences: umwelt. According to John Vaillant, author of The Tiger: A True Story of Vengeance and Survival, “The ability to step inside the umwelt ‘bubble’ of another creature is not so much a newfound skill as it is a lost art.” Faiers has spent many years trying to grasp the umwelt of the animals in this forest.

Snares are placed sporadically. You have to stick your head right into the fir boughs to find the almost-invisible thin silver noose. This kind of trap supposedly claims instant death. At the edge of Faiers’ trapline, he has nailed signs into trees warning: Active Trapline, Killing Traps.

The mechanics seem deceptively simple: one minute a wolf is padding through the woods, and then, zip, lights out. But as one old-timer says, “To catch a marten is very easy. But, when I catch a coyote I feel really good because I outsmarted him. I used my wits. It’s kind of like a puzzle.”

Faiers squints into a mesh of understorey, quietly observing hundreds of tracks that dash in and around his snare. He pauses, then cuts the sled engine. Winter silence settles, tucking the evergreens into its frozen fold. On a natural ledge, a coyote lies motionless, feet perfectly placed one on top of another. Snared.

Faiers runs his hand through the coyote’s fur, stroking its back while his nephew runs back to get the kids. They return, rosy-cheeked, keen to lug the animal down and then up the small bank. The coyote’s body brushes a line across the snow. Snowflakes land and the tracks — a set of two — are soon covered in white. What remains is a scent, invisible to humans, but to the animal nose it is a chorus of calls: who is the predator, who was the prey.

Trappers therefore use scent to lure animals into their traps. On a shelf in his garage, one trapper keeps jars of tar-coloured stickiness variously labelled cat piss, anise seed and beaver castor. An irresistible attractant for many animals, the latter is used by the perfume industry to create a woody or leathery scent. Top-grade beaver castor sells for $70 a pound. Trappers are careful not to leave traces of engine exhaust or oil around their traps. Some wear waders or tuck their boots into plastic bags to avoid dragging foreign smells near their sets.

Snares are placed sporadically. Almost invisible, you have to stick your head right into the fir boughs in order to find the thin silver noose. This kind of trap supposedly claims instant death.

But there is another scent, one that cannot be bottled or hidden. According to Herald Friedenberger, a 71-year-old trapper from Nakusp, “If there’s hate in you for what you’re doing, the animals will smell it and they won’t come near.”

Snow drips from the pine trees around Friedenberger’s property. His plaid shirt stretches across his ex-logger shoulders and his jogging pants are tucked into gum boots. “I get emotional,” Friedenberger says. “I will fight to keep the rights to do this.” He wipes tears from the corner of his eyes. Friedenberger’s sadness comes with age. The crust built up over years of hard work is breaking down, exposing life’s underbelly. “We are losing so much,” he says. “People from the city want to live in the country but they want to take away what we do here. We don’t go out to the bars; we trap.”

Trappers of this generation take with them a history, not only of the trade, but also of the land they have been meticulously observing throughout their life. It’s often difficult for people outside of the hunter-trapper sphere to understand the pairing of wilderness appreciation with a need to trap or hunt animals. But public officials tasked with wildlife management appear comfortable with the current state of affairs.

Garth Mowat, senior wildlife biologist with the BC provincial government assures, “I’m convinced that the registered trapline system does not present much risk to the conservation of fur-bearers or they would have changed things in the last 80 years,” he says. “And so far they haven’t.”

Mowat grew up trapping and has a good grasp of all the activity entails. Draining the trapline of every last animal would end a trapper’s career. Ideally, trappers keenly observe species and adjust their trap sets accordingly. However, as Mowat points out, “There are always bad apples in every group, in everything you do.”

Bad apples notwithstanding, it doesn’t change the fact that animals have a few things working in their favour. Chiefly, the fur trade is simply not as lucrative as it once was. Only half of the traplines in British Columbia reported activity in the last five years.

On their Fur Is Green website, the Fur Council of Canada likes to tout their product as being a renewable resource that is durable, recyclable and biodegradable. Although anti-fur organizations contest these and other claims, fur and the fashion industry still snuggle up to one another. And whereas a consistent -30°C winter in Russia or China may jack up fur prices for fashionistas dreaming of being swaddled in marten or lynx, a soggy winter can have the opposite effect.

Even if a warming climate sends the price of fur spiralling downwards, it’s still not all roses for fur-bearing species. Knocks against trapping include the beaver, once nearly decimated, the risk of accidentally capturing an endangered badger, or the forest’s lack of fisher, a species that once fetched $750 a pelt. But according to Mowat, “Wolverine are the fur-bearing species I would be most concerned about in terms of trapping.” And rightly so.

“People from the city want to live in the country but they want to take away what we do here. We don’t go out to the bars; we trap.” – Herald Friedenberger, Nakusp

Doris Hausleitner, a Nelson-based biologist, is researching the abundance and connectivity of wolverines in the Selkirks and Purcells. “We’re trying to monitor the numbers before they are endangered,” she says. Although her research may lead to restrictions on wolverine trapping, local trappers are still keen to help collect data. When asked about her relationship with them, she says, “It’s a huge landscape to cover. They are out there, and they know the best access routes. We all want the same thing: a sustainable harvest.”

Colby Lehman helps Hausleitner with her research. Transplanted from Calgary into the Kootenays, Lehman is an unlikely 30-something trapper who grew up reading old animal books from his dad’s antique store, including The Collected Works of Grey Owl. Lehman co-owns a 67,000-hectare trapline near Salmo with two friends. At the BC Trapper Education Course, a requirement for anyone seeking a trapper’s license, Lehman recalls, “We were sitting in a room with 10 guys, all of whom would fall under the redneck category. The masculinity in that room was unbearable at times. I felt my beard grow as I was sitting in there.”

Now in their sixth winter, it was actually an unabashed love of skiing that first drew the trio to the line. Lehman remembers his first meeting with the trapline’s neighbours. “They were looking at me standing on my new pair of Armada JJs and they’re like ‘You are the new trapper?’ I thought, ‘Oh my god, they think I’m an idiot.’”

Regardless, Lehman takes his newfound métier seriously. To set and check his marten boxes, he slaps on skis and skins up through an old-growth forest dripping with lichen. Learning how to trap has helped him slow down, he says, to stop and look at what’s happening around him. Over the last few seasons, Lehman has met the annual requirement of either 50 pelts or $200. “It feels pretty cool to meet my trapline objective on skis,” he says. “I feel like I’m earning my stripes.”

Basking in the glow of his trapline cabin, Lehman cooks an untraditional yet delicious backwoods dinner: Moroccan couscous, orange-mint salad and chickpea stew. As he prepares the food, a splayed-out marten pelt dries next to Gore-Tex jackets and a pair of skis. Although originally intrigued by the romanticism of trapping, Lehman admits, “I don’t emulate the old trapper persona in any way whatsoever. I’m not wandering around the woods with fur on.”

On the other hand, Normand Gagné is. In his late 70s and still tightly packed with muscle, Gagné is a descendant of the coureurs de bois, the first of Canada’s non-native trappers. In earlier days, Gagné travelled the world performing lumber sports shows at the likes of Disney World, filling his log home with box upon box of trophies. Now, on the parking lot of Cranbrook’s ice rink, he stands at the foot of his original tenure, the bulk of his trapline still running behind the houses and downtown alleys. These days, he says with his still-thick Québecois accent, he traps “noo-ee-sonce” animals, such as beaver and muskrat. Gagné’s red VW Jetta skids along the icy road as he drives his line. He pulls over at Hidden Valley Creek and steps out of the car clad in a raccoon fur hat, beaver fur gloves and a sheep-skin jacket. He definitely looks the part.

Gagné explains that for most species, the trapping season stops by mid-February. Fur deteriorates in summer. Easy-travelling snow melts. But with their skins preserved by water, beaver and muskrat can be trapped right into April. Gagné plans to trap beaver on the Moyie River in his canoe with his grandson. The river runs clear throughout the year and, as a result, the beaver here are tinged blue as opposed to being swampy brown.

He winces while slinging an axe over his shoulder, an injury he recently acquired while ice-fishing. His pain, both present and past, have made him think about the animals he has trapped. “When an animal suffers, I feel terrible,” he confides, pointing out that Canada leads the way in humane trapping standards. The very notion of humane trapping may seem like an oxymoron, but Gagné is comforted by the fact that traps today are less likely to inflict pain on animals than previously, when rules were slack or non-existent.

Since childhood, Gagné has seen environmental changes from the ground up. Tromping through the snow, he repeats the same mantra: He loves nature and he’s worried about the future. “Our little planet is sick; she’s dying,” he says. “She’s got fleas. You know who the fleas are? Us. The humans.”

Emily Nilsen

Emily Nilsen is a Nelson-based writer originally from Vancouver. Her work has been translated into Norwegian and Spanish and published in literary journals, magazines, and newspapers.

Related Stories

Eight Minutes in British Columbia

Check out this epic re-edited segment of James Heim shredding BC mountains from Matchstick Productions. Quality action…

The Hippie Utopia That Was Lund, British Columbia

A new documentary chronicles the love, uncertain liberty and all-American pursuit of happiness that found its way to…

Coast Modern Architecture

I just spend a couple of days at Baldface Lodge following abstract artist Jeremy Down around the mountains while he…

Patagonia Goes Fair Trade

This is big news. Patagonia Inc., the outdoor apparel company and CMC partner, is proud to announce its plans to offer…