Born from the currents of the Kananaskis, a Calgary company is helping kayakers and inland surfers navigate the waters of bureaucracy and hydromechanics. The goal? Righteous times on your neighbourhood river. By Kevin Brooker.

Neil Egsgard knows better than anyone that acts of altruism often begin with naked self-interest. The Ontario-raised Calgarian merely set out to restore his home surf break on Alberta’s Kananaskis River after the water feature was destroyed by an ill-conceived redesign. Thousands of unpaid hours later, Egsgard and his friends succeeded in creating the glassy, endless wave of his dreams, dubbing it the Mountain. “But this selfish quest,” he admits, “quickly grew into a project to change the world.”

https://youtu.be/_0GvAIY9hyQ

Feature photo by Robert Levesque.

In 2008, Egsgard quit his high-tech job and partnered with a fellow river surfer, Jacob Kelly Quinlan, to start a company called Surf Anywhere (SA), now the world leader in the development of river waves. Egsgard then spent six years exploring the leading river-surfing locations, from the Snake River’s famed Lunch Counter wave near Jackson Hole, Wyoming, to the sport’s cradle, the Eisbach in Munich, Germany, a two-kilometre, human-made channel where a standing wave was first ridden in 1972.

As for custom-building waves, “Almost every city is located on some sort of river, so potential sites are virtually unlimited,” notes Egsgard. But the key to enticing city councils is explaining urban river surfing’s three-part win: First, it’s an economic hub fuelled by board sales, lessons, and beer-guzzling spectators, something you’ll see at created sites in Reno, Nevada, Bend, Oregon, Boise, Idaho, and Missoula, Montana. Second, the place becomes an instant cultural centre. And third, not only can waves be built with zero environmental damage, when properly designed they actually improve the health of what are often human-afflicted waterways. Meanwhile, people playing in that river are much more likely to become its environmental stewards.

And it’s stewardship, says Egsgard—much of it pro bono—that lies at the heart of the SA development model. “Early on we realized that the hardest part is everything other than designing and building the wave.” Surf Anywhere begins the process by coaching locals who have identified a potential site to organize into the non-profit society necessary to front a project, then contributing enough technical and economic-impact information to trigger grants or private donations. Only then can SA start getting paid for the guidance that will eventually enable hired river engineers to properly see the project through. Having made an intensive study of the bureaucratic maze that inevitably arises, SA’s mission is to avoid pitfalls. “Eventually it becomes a municipal project and goes to tender, after which it’s pretty much out of the control of the local backers. So we need to make sure that the process is secure enough that it doesn’t result in failures.” All told, a project can take about two to 10 years.

And it’s stewardship, says Egsgard—much of it pro bono—that lies at the heart of the SA development model. “Early on we realized that the hardest part is everything other than designing and building the wave.” Surf Anywhere begins the process by coaching locals who have identified a potential site to organize into the non-profit society necessary to front a project, then contributing enough technical and economic-impact information to trigger grants or private donations. Only then can SA start getting paid for the guidance that will eventually enable hired river engineers to properly see the project through. Having made an intensive study of the bureaucratic maze that inevitably arises, SA’s mission is to avoid pitfalls. “Eventually it becomes a municipal project and goes to tender, after which it’s pretty much out of the control of the local backers. So we need to make sure that the process is secure enough that it doesn’t result in failures.” All told, a project can take about two to 10 years.

As for designing the wave, Egsgard has put his BSc in physics and mathematics to good use. “River waves have a very narrow tolerance to get them just right,” he says, a degree of precision that was often ignored in the early days of human-made whitewater features. Much like the first wave of skateboard parks, where lowest-bidder contractors were often clueless, “A lot of bad builds took place. Too much art, not enough science.”

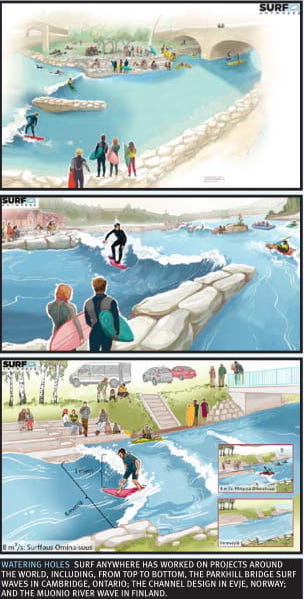

Currently, SA is consulting on sites in Norway, England, the Czech Republic, and even near the Arctic Circle in Finland. One of its finished projects is the redesign of the marquee surf wave at the Bend Whitewater Park, which happens to be the local break of surf icon Gerry Lopez. Like many modern builds, it includes pneumatically controlled kicker plates that can change the wave style as well as adjust to different flow rates. Whereas different shapes may be preferred by, say, kayakers, Egsgard points out that “A properly designed surf wave will be enjoyed by any river craft.”

“I rarely surf oceans now,” says Neil Egsgard. “They’re inconsistent. But when I go to a river, I know the wave will be there. Plus, you get more wave time than you ever would in the ocean.”

Back home in Canada, SA continues to put the word out. “There are people in Fernie and Golden who are in the exploratory stage,” says Egsgard. Ironically, despite its many rivers, British Columbia has only a few surfable natural waves, and they tend to be short-lived and seasonal. “Deep rivers aren’t suitable, but side-channels can work. We can build a good wave with flow rates as low as 10 cubic metres per second.”

One prime candidate? Surf Anywhere’s hometown of Calgary, where there’s currently a well-subscribed surf wave right downtown on the Bow River. Surf Anywhere has presented the city with a plan to create an urban beach featuring state-of-the-art waves plus other aquatic amenities. Total cost is projected at around $6 million, but what’s got civic mandarins excited is the estimated annual $1.7 million of economic spin-off. Imagine if they were to actually try this challenging but addictive sport. “I rarely surf oceans now,” says Egsgard. “They’re really far away and they’re inconsistent. But when I go to a river, I know the wave will be there. Plus, you get more wave time than you ever would in the ocean.”

Kevin Brooker

Kevin Brooker is a Calgary-based freelance writer with a generalist bent. Despite the geography, he considers himself part of the Coast Mountain community. As a sometime Vancouverite, he only occasionally misses the rain coast. His ongoing column in KMC has a cult following.

Related Stories

Trailforks for Paddling? A Calgary Company is Making it Happen

Simon Coward of Aquabatics in Calgary is spearheading a project to create the equivalent of the popular mountain biking…

Calgary Outdoor Expo and Festival Oct 30-31

The first-ever Calgary outdoor expo and festival is set to take place this upcoming Saturday and Sunday, next to…

The Coldsmoke Comes to Town

The Kootenay Cold Smoke Powder Fest is a grass-roots gathering where both experienced and debutant backcountry skiers…

Surf Canada Now Ranked Top 10 In The World

Thanks to an historic showing at the World Surfing Games in Japan, the Surf Canada team is now ranked 10th overall in…

Sick Pics: Tofino’s 10th Rip Curl Surf Comp

Thirteen-year-old Canadian surfing phenom Mathea Olin slayed it at the Rip Curl Pro Surf Comp in Tofino this past……

Tofino’s Surf Sisters Are Queens of the Peaks

The global cold-water cosmos knows Tofino, British Columbia's Surf Sister, an all-inclusive school that has stewarded…