It’s been 20 years since the world lost Guy Edwards. We look back on the climbing legend’s antics and accomplishments in the Kootenays and beyond. By Andrew Findlay. Photo by Kari Medig.

Years ago, I clawed my way up the northwest ridge of Mount Sir Donald in Rogers Pass, part of a cumbersome group of five. About two-thirds of the way up the 700-metre-long route, a guy came sailing past us, sporting shorts, a fanny pack, running shoes, and a curly mop of hair that looked like a collection of bed springs. “That’s Guy Edwards,” I thought, but before I could strike up a conversation, he had disappeared far above us, strolling effortlessly up the exposed low Class 5 terrain.

I didn’t know Edwards, but I certainly knew of him from photos in climbing journals, first ascents recorded in guidebooks, and his legendary globetrotting mountain adventures. His climbing resumé is as varied as it is long. He seemed to be everywhere: the desert towers of Mali, Patagonian granite, Kyrgyzstan, Peru, India. No chunk of rock was too obscure.

Some names shine bright on the landscape of Canadian climbing and mountaineering lore, and Edwards is definitely one of them. Two decades after he and climbing partner John Millar were swept to their deaths in an avalanche on the still-unclimbed northwest face of Alaska’s notorious Devil’s Thumb, his boundless energy; prolific new routing; and diverse skill on ice, rock, and steep alpine faces—not to mention his sharp mind and quirky sense of humour—are still fondly remembered.

Born in 1972, Edwards grew up in Vancouver, and by age 20, he was already one of the most well-rounded alpinists in Canada. He also had a gift for the absurd. In an attempt to shave seconds off his solo speed ascent of Pigeon Spire in British Columbia’s Bugaboos, he famously stripped naked and raced up the peak’s 455-metre-long 5.4 West Ridge and back in 18 minutes. Most roped parties take a few hours to complete the granite arete. “He was one of my heroes,” says Nelson, British Columbia-based engineer Cam Shute, who first met Edwards through the Varsity Outdoor Club at the University of British Columbia. He remembers nervously belaying Edwards as he nonchalantly ran out long sections of stiff Squamish crack climbing. Beyond his climbing talents, Edwards had something intensely anti-establishment about him. He could be a cheeky provocateur, questioning consumerism and the evils of car ownership while bumming a ride to the crag. “He was quirky, curious, and endlessly psyched,” Shute says. “And he also had this frugal rejection of capitalism.”

Edwards’s ethos also rejected sponsorship, self-promotion, and convention of any sort. It made for funny conversations, says Nelson photographer Kari Medig. He was introduced to Edwards in the late 90s, when the latter was working as a geological engineer in Cranbrook, British Columbia. For Edwards, gainful employment was not an end, it was a means, at best. “He had a totally different way of looking at the world,” Medig says. For example, Edwards questioned why anyone would work during the day when they could work at night during the dark hours. And that’s often what he did, catching winks under his desk so he could go adventuring after sunrise. Medig remembers him being genuinely disappointed, even incredulous, when his boss told him to start clocking daylight hours at the office.

In an attempt to shave seconds off his solo speed ascent of Pigeon Spire in British Columbia’s Bugaboos, he famously stripped naked and raced up the peak’s 455-metre-long 5.4 West Ridge and back in 18 minutes.

Although Edwards partnered up frequently with accomplished alpinists like Sean Isaac, with whom he earned the John Lauchlan Memorial Award for their trip to Patagonia’s Torres del Paine in 1997, he didn’t discriminate. Otherwise Medig would not have ended up ice climbing with him in the East Kootenay’s Bull River Valley and even establishing a new route on Mount Farnham’s southeast ridge.

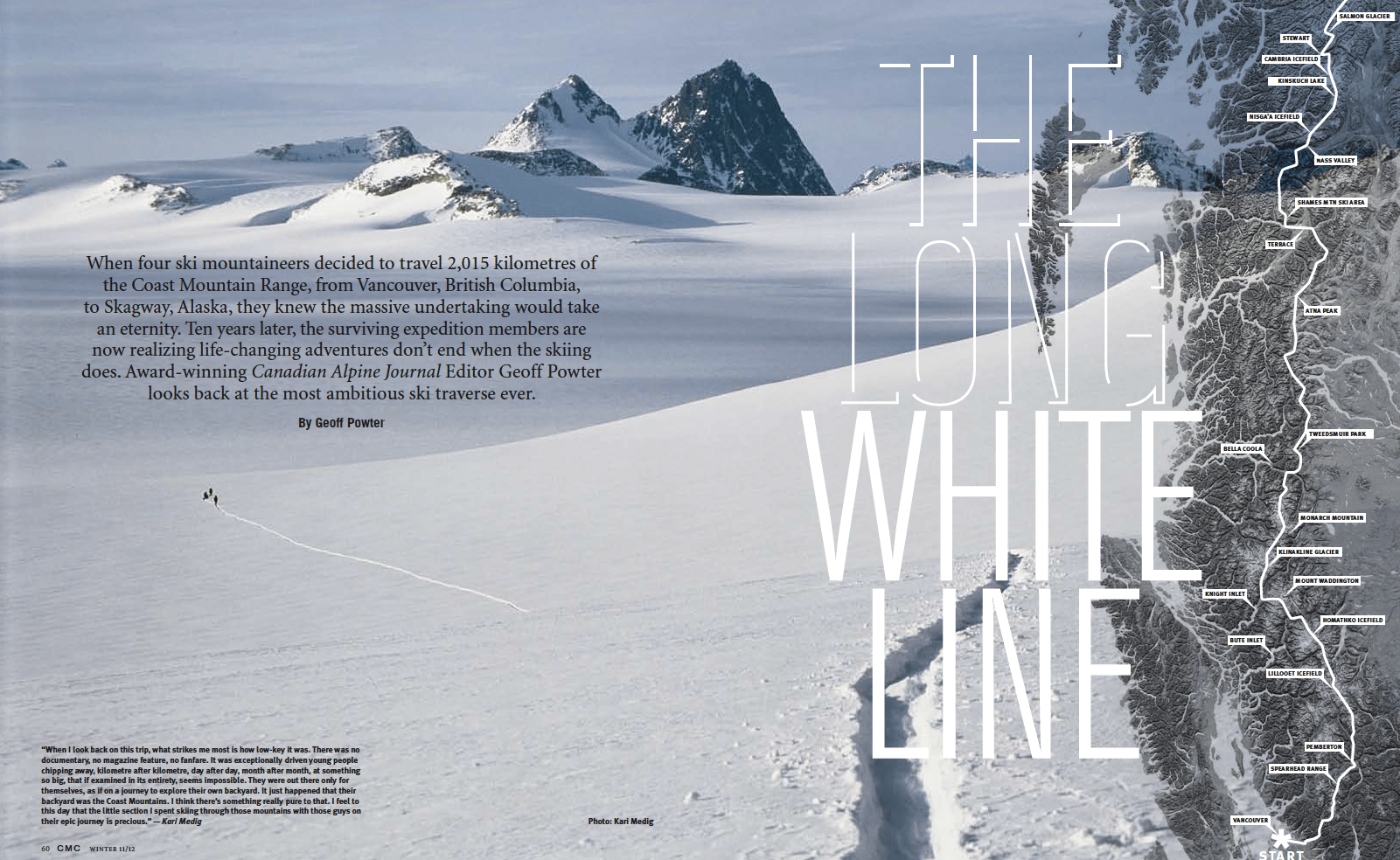

Medig says he wasn’t a climber then, and he still isn’t. Edwards just had a way of rallying partners to a cause.Medig went on to join him, Millar, and Vance Culbert for a month-long portion of their epic Coast Range ski traverse from Vancouver to Alaska. He says what most impressed him about Edwards was his unwavering commitment to human power. For example, when the foursome dropped into the Bella Coola River Valley, they hitched a ride into town. The next day, staying true to the trip ethic, Edwards returned to walk that same section of highway. “He was just a super fun and inspiring guy to be around, and he was extremely intelligent,” Medig says. “He was also totally anti-gear sponsorship. He’d find the oldest crap and make it last forever.”Edwards never made it to his 31st birthday, but he blazed through his brief time on the planet with an appetite for fun and adventure. He didn’t do it for the recognition, he did it for the sheer joy of being out there, and that is his greatest legacy.

Andrew Findlay

Andrew Findlay is an award-winning journalist and photographer with a home base on Vancouver Island. Born and raised in British Columbia, he continues to draw inspiration from the people, places, triumphs and travails of the Canadian West, however he ranges across the globe in pursuit of stories. Andrew’s journalistic interests are many; he enjoys peeling back the complex layers of social, environmental and business issues, but is also inspired by travel and outdoor adventure. Magazine and newspaper assignments have taken him to lands and cultures as diverse as the Great Bear Rainforest of BC, the remote mountains of northwestern Guatemala and the frozen ice hockey ponds of northern India.

Related Stories

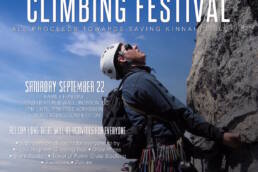

Olympic Climber To Speak at Kootenay Climbing Festival 2018

The Kootenay Rock Climbing Festival returns September 22-23, 2018, and will feature Olympic climber Jen Olson and…

An Ode to Montana Climber Hayden Kennedy

In the wake of the tragic news about Hayden Kennedy's death, we reflect on how he lived with conviction and confidence,…

The 2015 Arc’teryx Climbing Academy Is Coming at You

Mark your calendars -- the Arc'teryx Climbing Academy in Squamish, BC is happening July 10-12, 2015!…

Exclusive – Kinnaird Bluffs Rock Climbing Area Saved!

The Mountain Culture Group has just learned that the Kinnaird Bluffs rock climbing area in Castlegar, British Columbia,…