Sweeping monopolization, unprecedented newsroom cuts, and the internet have done great harm to local journalism. Resort towns and rural regions throughout Western North America are no exception, with newspapers and radio stations battling persistent financial uncertainty. Will communities ever be as critically well informed as they once were. We report on the state of the press. By Kevin Brooker with additional reporting by Darren Davidson.

Back in 2010, the newspaper industry was collapsing throughout the Western world, although nowhere more poignantly than in Nelson, British Columbia. At the time, the Nelson Daily News (NDN) still occupied its prime downtown location. It had a well-staffed newsroom and a workhorse press, complete with printing craftspeople whose careers had begun in an era when type was cast in molten lead. The paper had a long and proud history as a daily—109 years, in fact—in just about as small and remote a city as could ever be expected to support one. It had, to varying degrees, fulfilled the local newspaper’s mythic role as an exposer of truths, a leader, a unifier, a righter of wrongs. Yet, in the same year that the Vancouver Olympics was boasting worldwide of British Columbia’s rosy-cheeked vigour and gleaming future, one of Canada’s rising titans of community newspaper ownership, Victoria’s Black Press, bought the NDN. The company had rolled into Nelson a few years earlier with a free competing paper called the Nelson Star. But just a few weeks after purchasing the NDN, the Black Press fired its 25 workers—some on staff for nearly 40 years—and closed the doors forever.

City dwellers may not understand, but for any North American who has ever lived in a distant outpost, the local newspaper has always played an indispensable role. As one Kansas editor, William Allen White, put it over a century ago, “Our little country papers seem drab and miserably provincial to strangers, yet we who read them read in their lines the sweet, intimate story of life.”

Newspapers were even more foundational to the development of the mountainous northwest. It is difficult now for us to imagine the isolation of human settlements in the years before some entrepreneur managed to import a 700-kilogram press via rail or steamboat or overland. The story of the 19th-century West is filled with accounts of towns destined for greatness that nevertheless disappeared when a speculative publisher failed to show up. The settlement patterns of Idaho, it is said, changed completely when what was to be the state’s first printing press tumbled from a mule train into a rushing river.

Once established, however, newspapers quickly became a bulwark of civilization in even the most rustic settings. They often displayed a two-pronged purpose, the obvious one being to inform locals about community doings, as well as offer capsule versions of the slightly stale news of the outside world. But they also discharged the universal frontier task of pure boosterism in order to lure permanent settlers, and they helped launch more than few political careers.

To a greater degree than city newspapers, the small-town versions stood atop their local media pyramid clear through the 20th century, unbothered even by the advent of radio and television. Television was not going to topple them, since it was never truly localized, and it turned out that mountain dwellers had only a limited appetite for a window on far-off Spokane or Vancouver.

Radio, however, was different. It could be programmed by people who actually lived in the community, and, with a dedicated team of news-gatherers, it could be both comprehensive and comparatively instantaneous. But that too decayed steadily. Greg Nesteroff is a veteran of both radio and print media who has worked throughout the Kootenays. He watched first-hand the cascading attrition of local radio, which began nearly two decades before the internet invaded like a supercharged pine beetle.

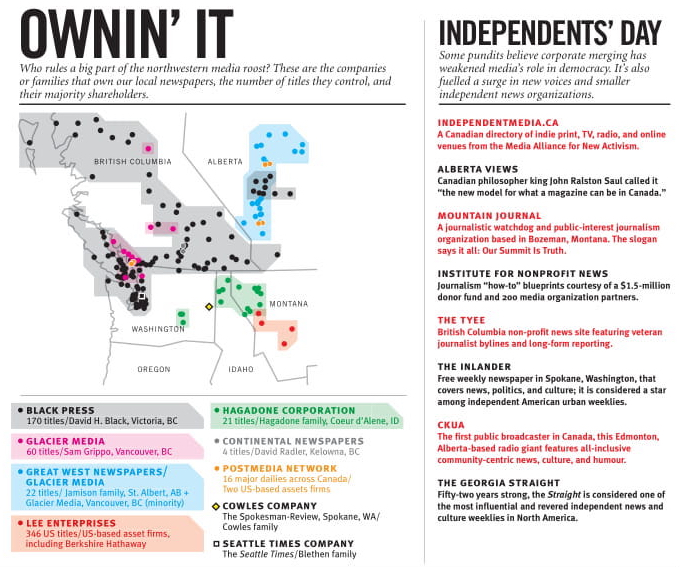

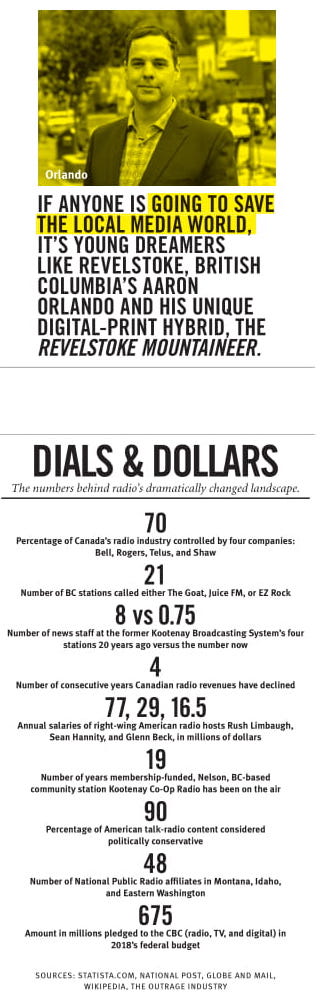

In the 1980s, consolidation was occurring throughout the industry, as corporations bought up small-town stations and applied repeater transmission technology that allowed newly formed networks to centralize programming in one studio while still pretending to be “from” each town along the chain, even as local microphones went silent. In short order, says Nesteroff, “There were really only two competing radio companies, although both have undergone numerous ownership, format, and name changes.” No kidding. As an example, Nesteroff describes one series of transactions from the extra-dizzying 1990s, “All in the space of about 12 years, Four Seasons sold its Kootenay stations to Okanagan Skeena, which sold to Telemedia, which sold to Standard Broadcasting, which sold to Astral, which sold to Bell.”

And to which Valhalla did that lead? In 2011, they were collectively rebranded as EZ Rock. Three of the stations, in Nelson, Trail, and Creston, once operated a formidable news network, with eight full-time reporters and newsreaders. Today, they have dwindled to one broadcaster, a deeply committed 25-year broadcast journalist who also cheerily tackles morning show duties.

Glenn Hicks knows all about that trend. After a high-profile career with stints at the South African Broadcasting Corporation and the venerable BBC, he took a job in the Kootenays in 2004 as the Vista Radio news director, overseeing a network of four widely scattered communities with a newsroom of six employees. But he faced a steady onslaught of demands from corporate headquarters obliging him to reduce the frequency and scope of newscasts. Coincidentally, with another town being added to his roster, his staff was cut in half. “It became very challenging to chase meaningful enterprise news,” Hicks recalls. “With a tiny staff we were often left to regurgitate press releases, while tackling the bigger stuff became extremely difficult and time-consuming with the pressures of having to present newscasts as well. Our court presence almost vanished, although I’m pleased to say that municipal reporting—city council affairs and the matters directly impacting local citizens—never diminished under my watch.”

DURING THE SAME PERIOD as radio journalism’s diminishment, newspapers began dying at an alarming rate. Across British Columbia, especially in this century, traumatized citizens have had a front-row seat for that death knell—the result of an especially voracious chapter of two corporations: Black Press, the private firm owned by the tough, hyper-entrepreneurial David Black, and a Vancouver-based publicly traded company called Glacier Media. In 2009, Maclean’s remarked on Black’s bold buying spree at a time when the stock value of newspaper holdings was in sharp decline, along with the fact that he was saving some papers from certain death. “I think it’s going to be a good business for a long time,” Black declared.

Meanwhile, Glacier Media—whose chairman, Sam Grippo, is an accountant by trade described by the Globe and Mail as both “eccentric and shrewd”—made headlines in 2006 when it purchased the remainder of Conrad Black’s Hollinger Inc. papers after the Canadian media baron’s fell from grace. From then on—while ostensibly competitors in the community newspaper business—Black and Glacier seem to have worked together to carve out their respective territories, eliminating two-paper competition and all but removing local ownership from the equation. In 2011, Glacier bought the province’s oldest newspaper, the Victoria Times Colonist, for $86.5 million. In 2014, Black bought 11 newspapers from Glacier, which was shuttering some of its other titles. All told, in the last decade Black has axed 10 newspapers, Glacier, seven.

Donna Macdonald, an author and former newspaper journalist, was a Nelson city councillor for 19 years. “The loss of the daily paper definitely affected how well people were informed about city politics and affairs,” Macdonald says, citing the closure of the NDN. “As a city councillor, I noticed that people’s knowledge had declined. They were unaware of even major city initiatives.” Even with the Nelson Star’s expanded online presence and a top-notch, albeit small, editorial team of two reporters and one editor, Macdonald believes that a busy, complex, and engaged city like Nelson deserves a bigger commitment to local journalism.

Economics within the shifting media landscape played a role as well. It’s inarguable that 10 years ago, most local papers were bleeding cash. At the NDN, competitors and even some staff believed it had simply lost its way and was financially doomed, in part due to high union wages. Enter Black Press, and its well-proven business model. The company, which now owns roughly 140 papers in British Columbia, Alberta, and Washington state, aggressively pursued a cost-saving strategy that centralizes accounting, systems, human resources, and, most importantly, the printing presses themselves. If, as the adage has it, freedom of the press belongs to those who own one, then Black Press clearly has a lot of it. It owns 10 between Calgary and Vancouver Island.

As for local content, like many other businesses, it’s about doing more with less. In any event, there’s little room for sentimentality. In 2010, with the NDN gone and Nelson’s grassroots paper, the 21-year old Express, about to close—due in part to Black’s aggressively low rates—the then-weekly Nelson Star bumped up to two ambitious editions every week. But with a financial toll taken by the battle with Glacier, falling national ad buys, and ever-increasing digital competition, the Star is now back to one issue a week. Its revised version is physically smaller, though thick with ads and inserts, and often includes copy from other Black Press papers along with community submissions. In 2011, the editor oversaw one paper and a fledgling website. Today the job has grown to include the content management of five papers, the website, and social platforms. Perhaps unsurprisingly, nine different people have held the Star’s editor position in as many years.

Small towns, big cities—it doesn’t matter. Consider Calgary, a city of 1.2 million with two dailies that once had their own huge buildings and presses. Now they’re both owned by the same corporation, former adversaries now awkwardly sharing a single tiny newsroom and outsourcing printing—one of them to Black Press itself.

All of this gets depressing for veteran journalists. “We are heading toward the lowest dumbing-down ebb,” laments Hicks. Smaller windows for news and bare-bones financial commitment to journalism, he says, mean reporters have only enough time to cover crime, accidents, scary weather, and items often submitted by community organizations, or worse, the public relations departments of advertisers. Meanwhile, the internet—the great disruptor—only increases its power. Hicks paints a future with more of what we’re already seeing: individual smartphones delivering quick doses of video, audio, and large-font text that’s easy on the eyes. Convenient. Basic. Shallow.

To a greater degree than city newspapers, the small-town versions stood atop their local media pyramid clear through the 20th century, unbothered even by the advent of radio and television.

IF ANYONE IS GOING TO SAVE the local media world, it’s young dreamers like Revelstoke, British Columbia’s Aaron Orlando and his unique digital-print hybrid, the Revelstoke Mountaineer. Armed with a master’s degree in journalism, Orlando chose the famed mountain town of 7,000 for lifestyle purposes and wound up toiling at the Revelstoke Times Review for six years. Toil is the right word. For most of that time, Orlando led a team of, well, one other person. When management decided that a lone go-getter could in fact do the entire job, Orlando bid farewell.

If he was going to be a one-man show, he might as well have an equity position. In 2014, he launched the Mountaineer with little more than a deep respect for the institution of journalism and a belief in the community. “Everyone is struggling in this media environment,” he points out. “There’s no sense complaining.” Rather than point fingers at heartless corporations, he says, “Journalists themselves need to shoulder the responsibility of saving journalism.” Along with colleague Alex Cooper, another ink-stained wretch, Orlando is attempting just that.

The Mountaineer has two faces. One is a fairly standard online array of short articles covering local news and events, usually updated several times daily. The other is a full-colour print magazine that appears monthly and tends to focus more on lifestyle, of which Revelstoke has plenty. Both are shockingly excellent given the limited resources at hand. “We don’t have official staff,” says Orlando. “It’s all contract. We have a web person, a design person, a part-time reporter, and about a dozen occasional contributors. We pay our photographers, we try to work with professionals and offer living-wage rates.” Orlando acts as creative director, putting in long weeks in winter especially, when he teaches part-time at Okanagan College Revelstoke.

As for the ad revenue that powers everything, Orlando says that income is split 75/25 print to digital. Alas, it’s a common refrain throughout the industry. As Nesteroff observes, “Websites generate only a tiny fraction of revenue of the print and on-air products, which is puzzling. We’ve built the better mousetrap, yet most advertisers would rather pay extra for the old mousetrap. I can’t quite explain it.” For Orlando’s part, he’s not optimistic that this will change soon. “I really don’t think an online news site is viable at all if it’s operated on a traditional ad model. We briefly tried Google ads, and that’s not going to work either.”

Meanwhile, back in Nelson—where the former NDN newsroom has morphed into a loft, a lawyer’s office, and a spa—a passion for journalism continues to fuel Bruce Fuhr’s Nelson Daily, an online newspaper in direct competition with the Star. It’s part of an all-digital news chain called Lone Sheep Publishing, founded in 2008 by webmaster David Livingstone and the recently deceased writer Adrian Barnes, with additional independent locations in Castlegar, Rossland, and Grand Forks.

Fuhr had been the sports guy at the NDN for years, but thrown out of that job, he decided that securing a franchise for an online publication was worth a shot. And it has been. “We’re actually making money,” he says, though like his lone staffer, City Hall reporter Tim Schafer, he has another full-time job. “People like what we’re doing. We’re local and we’re different. Social media is good at some things, but when it comes to reporting things like fires, accidents, controversy at City Hall, parking issues—well, that’s what draws the most eyes.” In this case it’s about 80,000 to 100,000 unique views a month. He’s fond of saying, “Our competition has bullets and we have a water pistol. But there’s a lot of power to it.” His biggest challenge these days is finding part-time reporters. “It’s difficult to train people,” he says. “Still, there’s some decent part-time money to be earned by anyone willing and able.”

IS THERE ANY FUTURE FOR local journalism absent mad quantities of passion? Actually, Orlando envisions a way that is radically different from most existing models. “I can foresee what you might call non-profit journalism,” he says, citing New York’s ProPublica, which performs Pulitzer Prize-level investigative reporting for public benefit, in which everyone is professionally paid.

Orlando also points out that Canada’s federal government has made noises about new regulations forthcoming, potentially allowing different sorts of tax credits and even charitable status for certain kinds of journalism. One way or another, he says, “I think it will take wholesale changes to enable the kind of journalism that people are still desiring. It also has to be non-disruptive. We don’t want to put people out of work.” Orlando is currently in the exploratory stages of a project for newsgathering across the Columbia region in interior British Columbia. Only time will tell what new models may emerge.

One thing is for certain: Canada isn’t especially long on angel investors like the Ford Foundation or Pew Charitable Trusts, which are among the well-heeled underwriters of ProPublica. Nor do we have the likes of television’s Maury Povich and Connie Chung, who founded a weekly print and online newspaper in Kalispell, Montana, called the Flathead Beacon in 2007. Cynics scoffed, but keeping well behind the scenes, the power couple has helped guide it to award-winning status with one of the most robust news teams in any North American weekly. Staff are paid like the professionals they are. Locals have come to love it.

Maybe more initiatives like that could start happening. Or the government’s pledge to keep journalism viable could some day bear fruit. Perhaps the large media companies might even come to reassess the value of quality reporting and commit more resources.

Aw, who are we kidding? Whatever we end up doing in this beautiful if slightly benighted part of the world, it’ll be all about the passion.

This year, Calgary-based Kevin Brooker will mark 40 years of working as a freelance journalist. Meanwhile, given the state of the industry, he is considering a new career as a cruise-ship gigolo.

Kevin Brooker

Kevin Brooker is a Calgary-based freelance writer with a generalist bent. Despite the geography, he considers himself part of the Coast Mountain community. As a sometime Vancouverite, he only occasionally misses the rain coast. His ongoing column in KMC has a cult following.

Related Stories

The story behind the photo edit

Many of you may have already read the piece in the winter issue on Rob Newsom. He's an interesting and gregarious…

Should Big Mountain Jesus Be Saved?

After 60-some years watching over his freeridin' flock, it looked as though the "Big Mountain Jesus" statue at…

Insane Mountain Beat Boxin’

We don't know who this guy is, or where he came from. He showed up at the Kootenay Coldsmoke PowderKeg Slopestyle last…

The Gathering at Red Mountain

This upcoming Easter weekend RED and POWDER Magazine are presenting the 2nd annual Gathering at RED. Come hang with…

The Gathering Returns to Red Mountain

Presented by Salomon, the Gathering at Red Mountain, an event of mountain photographers, filmmakers, and artists is…