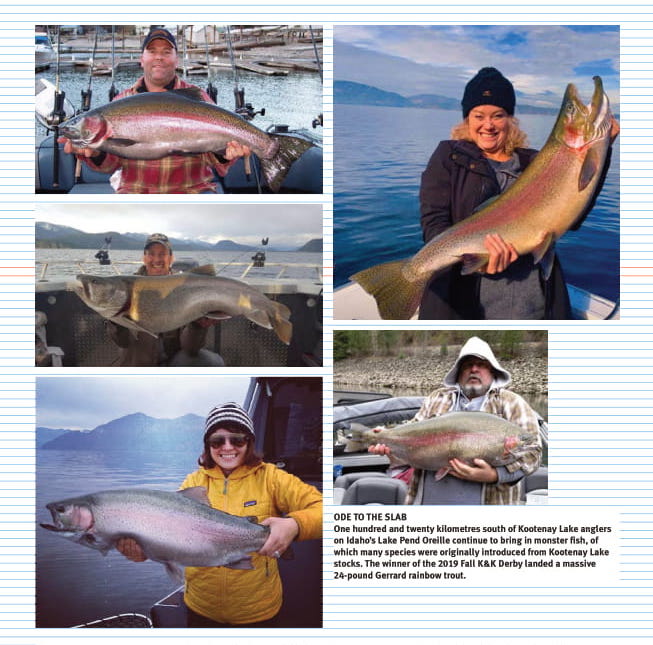

Not so long ago it was home to one of the most astounding fish populations in North America. Gargantuan endemic Gerrard trout, which could grow to 25 pounds or more, thanks to their main food source, the Kokanee, made Kootenay Lake famous to anglers throughout the West. Since 2014, however, the once mighty Gerrard struggles to reach five pounds. One hundred miles to the south in Idaho, however, Lake Pend Oreille, stocked with Gerrard and Kokanee from Kootenay Lake is thriving, producing trophy fish year in year out. How is that possible you ask? As our intrepid journalist discovers, the answers are not so easy to catch. By Jeff Gailus. Photos by Bryce Duffy.

The invitation comes by text early one March morning. “The Gerrards are running. Get your ass over here.” I save and close my overdue writing assignment, pack an overnight bag, kiss my wife goodbye, jump in the car, and tear out of Missoula, Montana. The next morning, I am roaring up the Clark Fork River, a mile or so upstream from Lake Pend Oreille, near Sandpoint, Idaho, in my guide’s aluminum Lund. We are in search of some of the biggest rainbow trout on the planet.

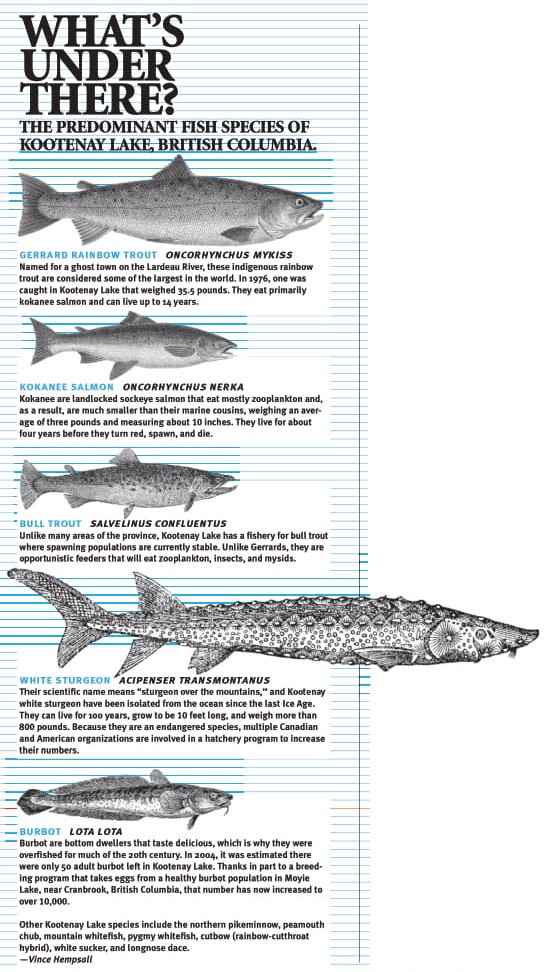

Such hasty decisions are made only when fish of prodigious size and strength are involved. As one of the world’s largest strains of rainbow trout, Gerrards are legendary. They can reach the size of your average first-grader and resist capture as fiercely as if they have spent their life at sea with sharks and orcas. The late Dr. Robert J. Behnke, an authority on the classification of salmonids, held Gerrards in the highest esteem. “Like rare estate wine,” he wrote in a 1988 column for Trout Magazine, “[the Gerrard trout] is a fish for special occasions.” I quickly learn that any time these giants ascend the rivers in early spring to spawn becomes a special occasion, no matter what deadlines and responsibilities are waiting for you at home or work.

My guide swings the boat around in the current and cuts the engine. We drift down the river in his secret spot, just off the cobbles. When the fish finally bites, the rod tip quivers for a moment and then lunges for the bottom. Out screams the line, metre upon stretched metre, until the monster on the other end decides it is time to rest. I take the opportunity to coax it back to the boat, only to excite it into another frenzy of piscine energy. Twenty minutes later, the biggest fish I have ever caught fills our net, a thick band of deep, coppery red running from tail to kype.

I gasp. It seems a beast of dreams, especially for an inexperienced angler like me. As a kid, I had caught spindly stocked rainbows in the rivers near my home in Calgary, Alberta, and some middling salmon in the Georgia Strait off Vancouver Island in British Columbia. But this is another dimension altogether, a wild fish full of ancient DNA that has been honed by the eons to sit atop every freshwater food chain in which it swims. After a quick picture, I hold it in the cold current to let it catch its breath; in a muscular flash, it is gone, continuing on to its biological destiny in the small creek that runs down from the mountains to the north.

A CENTURY AGO, southeastern British Columbia’s Kootenay Lake was the only place to catch a glimpse of these remarkable fish, but no one then really knew how special they were. For decades, there has been considerable misunderstanding about what the Gerrard trout actually is. Roderick Haig-Brown, an iconic British Columbian angler, writer, and conservationist, called it a Kamloops trout, and wrote (incorrectly) in his 1939 classic, The Western Angler, that it is “simply a subspecies of the steelhead.” Today, too many anglers and writers still use the name “Kamloops,” a term that refers generally to big rainbows caught in the vicinity of Kamloops, British Columbia, and belies the evolutionary specificity that makes Gerrards such a wonder.

Taxonomists generally agreed that Gerrards are an ecotype (or strain) of Columbia River redband trout that evolved over millennia in Kootenay Lake and the Lardeau and Duncan rivers upstream, near the ghost town for which they are named. But questions remained. Do Gerrard trout exist in other lakes? Are all the rainbows in Kootenay Lake Gerrards? If so, why do some max out at 20 inches, while others grow as big as Chinook salmon? Modern science, particularly genetics, has helped clear things up. Turns out there are actually two strains of rainbow trout in Kootenay Lake, each playing out its evolutionary destiny. The run-of-the-mill variety eats insects and spawns in smaller tributaries; they are smaller, rarely reaching 20 inches. Gerrards, by contrast, eschew bugs in favour of the sweet, fatty flesh of the kokanee, a land-locked sockeye salmon that was trapped inland along with the Gerrards thousands of years ago. It is this, dare I say, cultural preference for high-calorie piscine prey that makes the Gerrard one of only a handful of wild rainbow trout strains that grow to preternaturally gargantuan size. And these native Gerrards are all born in a 150-metre stretch of the Lardeau River just below Trout Lake, which provides a measly 1,250 square metres of optimal spawning habitat. It’s like an endangered bird species that only breeds on one island in the entire world (the waved albatross of Española Island in the Galápagos, for instance, or the Whenua Hou diving-petrel of Codfish Island in New Zealand), a spatial oddity that leaves them vulnerable to the perils of stochastic events. “Gerrards are a super-unique ecotype and the only wild natural population. There’s a really high conservation value to those,” says Matt Neufeld, fish and aquatic habitat section head in the Kootenay region for the BC Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development. He goes on to explain that rainbows just don’t reach a certain size unless they are eating nothing but kokanee.

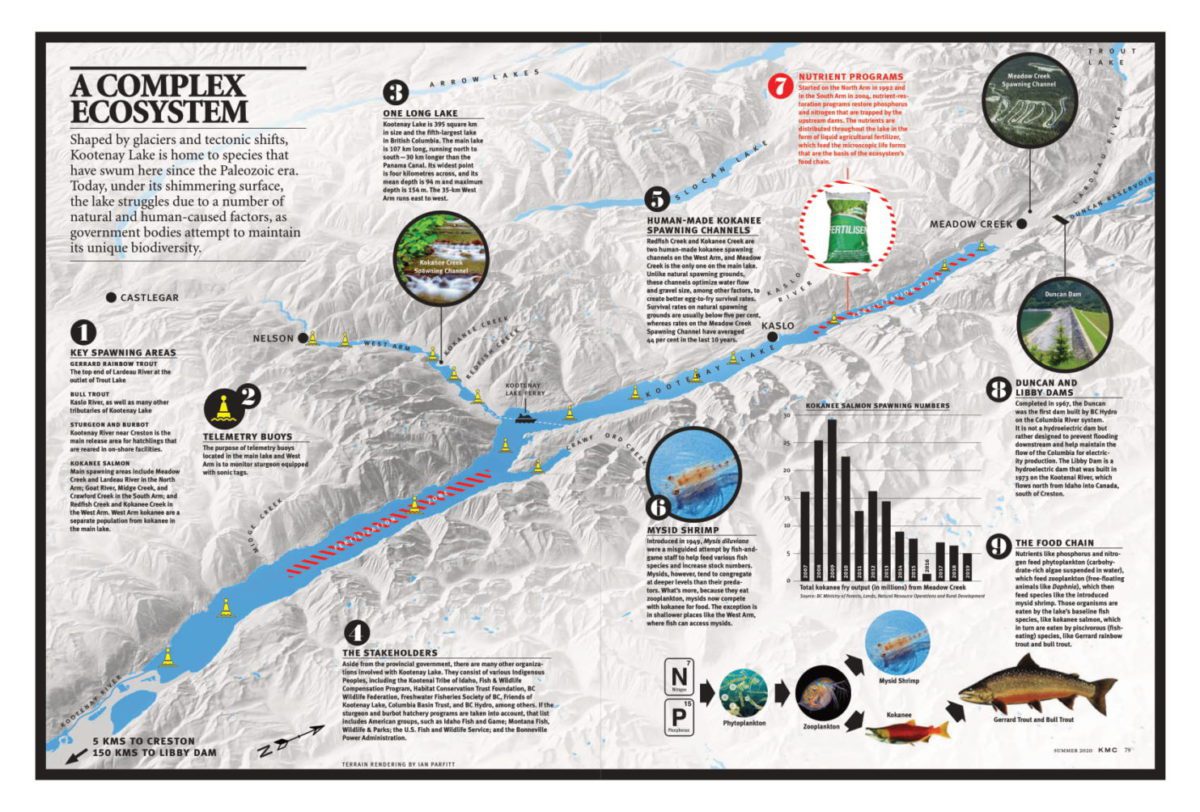

From the perspective of the naturalist, what makes these unique, top-shelf predators so special is their successful adaptation to exploit a specific niche with the expertise and chutzpah of a Wall Street wolf. Fisheries managers also love Kootenay Gerrards because they are the only wild, non-GMO source of massive rainbows and they quickly put smiles on anglers’ faces and increase tourism dollars wherever they are introduced. That is why anglers and fisheries biologists all over the continent were aghast to learn the kokanee population in Kootenay Lake had all but collapsed by 2015, followed soon by the Gerrards. The fall was catastrophic. The number of spawning kokanee plummeted from an annual average of 1.5 million to as low as 20,000 in 2015, and large Gerrards became frighteningly scarce. Estimated angler days soon followed, dropping from 40,000 a year in the early to mid-2010s to 12,000 or so in 2018.

I learn of the Great Kootenay Kokanee Collapse a week after my experience with Lake Pend Oreille’s rainbow giants in March 2016, and I reach out to Kerry Reed, owner of Reel Adventures Sport Fishing Charters out of Nelson, British Columbia, to get the details. Reed runs one of the biggest guiding outfits in Nelson, and although he leads trips on a variety of lakes and rivers and the Pacific Ocean, his bread and butter is Kootenay Lake. At least it used to be. The number of trophy Gerrards plummeted to such a degree that his business was starting to collapse along with the fishery. He says the 2012–2013 season was epic, and his clients enjoyed a record catch of impressive fish. Everyone was happy. Then, calamity. “It finally hit a wall in the fall of 2014, and 2015 only confirmed it,” he says. “There’s definitely a problem.”

The cause of the collapse is a matter of some conjecture and a source of simmering disagreement. Some say it was the Duncan Dam, the first of many dams built to satisfy Canada’s obligations under the Columbia River Treaty. Completed in 1967, the dam blocked access to important spawning habitat and trapped important nutrients (mostly phosphorus and nitrogen) that feed kokanee’s primary food source, plankton. Others point to the arrival of Mysis diluviana, a small, non-native shrimp-like crustacean that was introduced from Upper Waterton Lake in 1949 and 1950. Also called opossum shrimp, they eat the plankton on which the kokanee rely, and such competition can reduce the amount of food available. Still others point to the addition of artificial nutrients to the lake, which began in the 1990s to compensate for the impact of Duncan Dam. Or, maybe it was just the overharvest of too many big Gerrards, the baby-making engines of the population, which anglers love to mount on their walls.

Neufeld, who grew up in Nelson and is an avid fisher, acknowledges that some “peripheral” effects may have contributed to kokanee decline, particularly the cold spring of 2012, which decreased the amount of planktonic kokanee food, and the arrival of the infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus in early 2013. But he says the consensus is that the biggest problem was too many hungry Gerrard trout that eat nothing but kokanee. “Between 2005 and 2008, we had three to four times as many Gerrards in the lake than we had before. We had an increase in spawners, and large spawners. By 2010, 11, 12, that number was way higher than we’ve ever seen for Gerrard spawners, over a couple of orders of magnitude higher [approximately 100 times more],”he explains. “Ultimately, that’s the biomass of predators that got on top of the kokanee population, and they weren’t able to compensate.”

Today, Neufeld says there are just 37,000 small, catchable Gerrards left in the lake, half of the amount in 2011. Kokanee spawner numbers, which doubled each of the last two years, were still just 60,000 this fall. Although Kootenay Lake is as beautiful as ever, it’s as if something irreplaceable, its soul perhaps, has been excised. Can it be replaced?

KOOTENAY LAKE AND Pend Oreille (“The Pond,” as the locals call it) are inextricably linked. They are both large, deep lakes created eons ago by melting ice sheets, and they both flow west into the Columbia River, their waters meeting a quarter of a mile north of the Canada–US border, near the town of Waneta, British Columbia. They are similar in size, though The Pond is twice as deep at 350 metres (1,150 feet). It’s so deep, in fact, that the US Navy tests submarine prototypes there; during World War II, it was the second-largest naval training ground in the world. Both lakes have been considered world-class fishing destinations for most of the last 75 years. Until now.

The Pond will be forever in debt to Kootenay Lake. As the legend of the Gerrard trout spread far and wide in the mid-20th century, anglers all over the continent began strategizing to get some of the fiery beasts into their waters. Idaho anglers knew they would do well in The Pond, and they were the first to transplant Kootenay Gerrards, in 1941. Introduced kokanee were waiting for them, and the Gerrard population thrived. Just six years later, an angler named Wes Hamlet landed a 37-pounder, setting a world record that would stand for 50 years.

As Kootenay Gerrards were stocked in other water bodies, these two sister lakes cranked out trophy fish after trophy fish for the next 45 years. Then Lake Pend Oreille anglers once again looked north with envy at the perceived success of the Kootenay Lake fishery, thought to have been buoyed up by the introduction, in 1949 and 1950, of Mysis shrimp. Anglers pressured Idaho fisheries managers to replicate the experiment, and they acquiesced. They brought Mysis shrimp from Upper Waterton Lake in 1966, and then procured more from Kootenay Lake in 1967 and 1968. For 20 years, Lake Pend Oreille offered the best of all possible worlds: kokanee populations so large they opened a commercial harvest, and a Gerrard fishery that rivalled even Kootenay Lake’s.

But nature works by its own set of rules and every lake is different, which we knew much less about in the 1970s. Unlike in Kootenay Lake, the Lake Pend Oreille kokanee did not grow bigger and more abundant. And then, in the 1990s, the kokanee population began to suffer. “All of a sudden, we were at risk of having the kokanee population decline,” says Andy Dux, Idaho Department of Fish and Game Panhandle Region fisheries manager. Dux, who has been working with the Lake Pend Oreille fishery for the last 11 years, saw the fishery collapse with his own eyes. “We had to do something about it,” he continues.

What they eventually figured out was that in the deep dark at the bottom of The Pond, the local lake trout population, which was introduced in 1925 and had lain more or less dormant for 50 years, had exploded. In the West Arm of Kootenay Lake, upwelling—currents cycling water from the bottom of a lake to the top—allowed kokanee and small rainbows to feed on Mysis near the surface, keeping the population in check. However, in The Pond, like most deep lakes, Mysis stay at the bottom of the lake during the day, only moving up in the water column to feed at night. This meant the shallow-dwelling kokanee and rainbows couldn’t access them during the day, and the Mysis filled their bellies with plankton each and every night—the very food the kokanee depended on for their survival. The Lake Pend Oreille Mysis population surged, and the deep-dwelling juvenile lake trout that fed on them multiplied in size and numbers. The result? Increasing populations of two big, aggressive predators, lakers and Gerrards, that continued to consume a prized kokanee population that had less and less food. Without intervention, the outcome was inevitable: the total collapse of the kokanee population.

It was a fisheries manager’s worst nightmare. Anglers are as fussy and obsessed a subculture as you will find, especially American anglers who have a lot of political clout and are used to having the best of all possible worlds, a static state that is nearly impossible to maintain in perpetuity. When humans tinker with natural systems—building dams, say, or introducing non-native species like trout and crustaceans—the law of unintended consequences tends to hold sway, and food webs can unravel faster than a ball of string in a kitten’s paws. To make matters worse, the biologists could see what was happening because they were conducting research, but your average local angler did not recognize that there was a problem, never mind a pending catastrophe. They were still catching kokanee (albeit fewer and smaller), and what angler doesn’t like an abundance of giant predatory trout to catch?

But the signs of apocalypse in The Pond only became more and more apparent. The kokanee population went from three million in 1993 to less than 50,000 in 2002. Five years later, the numbers had dropped to 10,000. Even anglers began to realize the writing was on the wall, and no one wanted to see the kokanee population disappear entirely, as it had ten years earlier in Montana’s Flathead Lake 320 kilometres (200 miles) upstream. So, in 2000, the state closed the commercial fishery and prohibited anglers from targeting kokanee. Anglers howled. The state’s most controversial move was to hire professional gillnetters from the Great Lakes to decimate the lake trout population, and then, in 2006, it put a $15 bounty on both lake trout and Gerrards. Idaho Fish and Game spent $1 million a year on eradication efforts. Many anglers thought they would never be able to fish for kokanee again, and that the days of giant Gerrards were over. Fisheries managers crossed their fingers and hoped the experiment would work.

It did. By 2015, when the kokanee population in Kootenay Lake was just 10,000 and Reed’s trophy trout clientele had disappeared, there were more than a million kokanee in The Pond. Idaho Fish and Game dropped the bounty on Gerrards, though it still continues for lake trout. They still gillnet lake trout, and have started to do the same for walleye, another non-native predator that has come down the Clark Fork River from Montana, just like the kokanee did. “Kokanee have rebounded to densities we haven’t seen in decades,” says Dux proudly, “and Gerrard and bull trout growth rates are outstanding. The trophy fishery, not just Gerrards, is outstanding. The only thing we’re struggling with is a good kokanee fishery. There are so many fish that the size is smaller and less interesting to anglers.”

Several fishing derbies a year bring anglers from far and wide to see who can catch the biggest Gerrards and lake trout. As the photos on the Deep Water Fishing Facebook group attest, the fish are enormous. The Oktoberfish derby in early October saw its best catch ever. The biggest Gerrard was 35.5 inches and 24.28 pounds, the largest fish since the derby started 15 years ago, and every one of the top three fish in each age class was over 20 pounds. A week later, Sophie Egizi, an eight-year-old girl from Sandpoint, set the Idaho catch-and-release record with a 36.5-inch Gerrard. The return of big fish has also brought big money. Dux says a 2012 economic analysis indicates that the recreational fishery on The Pond is worth about $15 million annually to the local economy. Next year they are doing another analysis, and Dux says he won’t be surprised if it tops $20 million.

///////

THE TURNAROUND IN THE POND, which allowed me the chance to catch the fish of a lifetime in March of 2016, is often heralded as a blueprint of sorts for the snafu in Kootenay Lake. Just ask Harvey Andrusak. He is a former regional fisheries biologist and director of the fisheries branch of the BC Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy. He is also the past president of the BC Wildlife Federation (BCWF) and remains the inland interior chair for the BCWF’s fisheries committee. He and his son, Greg, who now works for the Ministry of Environment, wrote the 2016 Kootenay Lake Action Plan as a guide to replicating The Pond’s success. He represents the BCWF on the Kootenay Lake Fisheries Advisory Team, and he is less than happy about the current state of affairs in Kootenay Lake. “I’m highly critical of the management regime and the managers on the lake, because the lessons should have been learned based on the Pend Oreille story,” he told me in a recent phone interview. “The guys down there really got at it,” he continued. “They turned it around and good on ’em. The lesson hasn’t really resonated here in Nelson and so we still have really small rainbows.”

At issue, says Andrusak, is the refusal of fisheries managers to reduce the number of predators, namely Gerrards and bull trout, in the short term, as was done in The Pond, so kokanee populations can rebound. When he was commissioned to write an action plan, Andrusak says he included an entire section on the importance of suppressing the numbers of predators. Before the plan was released to the public in May 2016, he says, that section was removed, and Andrusak says government bureaucrats refuse to talk about, much less implement, the need to manage the lake back into balance. “It is ironic, really,” he explains. “The original Gerrards did come from Kootenay [Lake] down to Lake Pend Oreille. The fishery is back on its feet the way it should be. It can be done. It’s having the will to do it.”

At issue, says Andrusak, is the refusal of fisheries managers to reduce the number of predators, namely Gerrards and bull trout, in the short term, as was done in The Pond, so kokanee populations can rebound. When he was commissioned to write an action plan, Andrusak says he included an entire section on the importance of suppressing the numbers of predators. Before the plan was released to the public in May 2016, he says, that section was removed, and Andrusak says government bureaucrats refuse to talk about, much less implement, the need to manage the lake back into balance. “It is ironic, really,” he explains. “The original Gerrards did come from Kootenay [Lake] down to Lake Pend Oreille. The fishery is back on its feet the way it should be. It can be done. It’s having the will to do it.”

Neufeld is not so sure an aggressive predator cull is the answer, in part because Kootenay Lake is different in many ways from Lake Pend Oreille. There aren’t any lake trout, for one thing, and he says the uniqueness of the Gerrards in Kootenay Lake means they need to be protected from “winking out.” “That’s what’s different from Pend Oreille,” he says. “You could just restock them if they wink out there, right? … Our predators are very important because they’re natural, wild, evolved populations.”

Nonetheless, the ministry is trying to decrease predator demand on the kokanee by removing some fish; last year, fisheries managers culled 400 adult bull trout from the Duncan River as they made their way from their spawning grounds to the lake, and anglers are now allowed to keep more bull trout and the smaller rainbows. The ministry is also stocking kokanee fry, 20 million since 2015, and adding nutrients to the lake to increase kokanee food supply. But Neufeld readily admits that stocking alone probably won’t remove the bottleneck. The survival rate of kokanee fry during their first year of life is just one per cent, and the survival rate of one- to two-year-olds has gone down the last two years. “If we can get through the next year and see a change in that one-year-old survival, we’re in the right place,” says Neufeld. “It’s hard to speculate, but if that changed tomorrow, things would turn around in short order, like less than a generation in kokanee.”

Still, the numbers are hard to square, and it’s difficult to see how kokanee survival rates can improve if predator numbers are not further decreased. Either way, nature always finds a balance, and only time will tell whether Andrusak is right that fisheries managers in British Columbia should better heed the lessons learned in Lake Pend Oreille.

Meanwhile, Reed says his business has been turned upside down. Tourists keep him busyish in the summer months, and his west coast fishery makes up some income, but it’s just not the same. “My busiest season used to be right now and throughout the winter for the big Gerrards. Now, it’s my off-season.” So what’s an idle guide to do? Last fall Reed packed his truck and boat and headed to Lake Pend Oreille for two weeks, hoping to hear again the scream of a fishing reel being tortured by a pissed-off Gerrard the size of a wolverine.

Jeff Gailus writes about the chaotic confluence of nature and culture from Missoula, Montana. Raised in Calgary, he is still recovering from the Alberta Advantage.

EDITOR NOTE: After this story was written earlier this year, the Kootenay Lake Angler Incentive Program was put in place: anglers are encouraged to catch rainbow and bull trout in the main body of Kootenay Lake and turn in the heads to local depots to enter a monthly draw for a prize worth $1,000 and the chance to win a grand prize of an 18-foot Kingfisher boat. According to the website, “The goal is to increase rainbow and bull trout retention from 50 percent of the fish caught to 90 percent. The trout are suppressing the survival of the kokanee, the primary food source of these predators. Encouraging anglers to catch and retain Kootenay Lake trout will give the juvenile kokanee a chance to grow.” For more information, visit: bcwf.bc.ca/kootenay-lake-angler-incentive-program.

Related Stories

Nelson Kootenay Lake Marketed As The Cat Ski Capital of the World

What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas, but what happens in Nelson Kootenay Lake you’ll want to share with your friends…

Big Think: Celebrating Kootenay Tech Entrepreneurs. Part 3 – Lorri Fehr of Columbia Lake Technology Center

Where some see the future as uncertain, or even imperilled, others see opportunity and hope. This Kootenay entrepreneur…