Up against the rugged and remote stage of British Columbia’s northern coast, a charismatic cast of Ursus arctos horribilis plays out a hairy tale of love, lust, and loss. Behold Monty, Rocky, Doze, and other bears of the Khutzeymateen Inlet, home to the highest concentration of grizzlies in the province. These are the bears of our lives. By Amanda Follett Hosgood.

In a remote inlet in northwest British Columbia, the injured grizzly limps his way along the shoreline. Holding a hind leg aloft, he picks his way carefully over slick rockweed and fallen logs, stopping occasionally to sniff the air or rub his chestnut fur against a branch — love notes left on overhanging cedar and spruce. I’m watching from a Zodiac with six other tourists and our guide, Sarah Elmiligi, who narrates the scene. “Now he’s smelling the branches,” she says. “Now he’s leaving his scent.” Six pairs of binoculars follow the grizzly’s painstaking progress. Elmiligi initially spotted the bear’s silhouette on a rocky outcrop, and we watched as he waded through chest-deep water, eventually pulling himself onto the shore with his distinctive step-hop gait. It is mating season in Khutzeymateen Inlet, located 45 kilometres (30 miles) from Prince Rupert, British Columbia, near the tip of the Alaska Panhandle. Rocky, like other males from miles around, is following the scent of Hot Chocolate, the only breeding female seen in the inlet this year. We left her frolicking in the next bay with Buddy, a young male with big aspirations.

Known for having the highest density of grizzly bears anywhere in the province, this area becomes a veritable swingers nightclub of coital activity for Ursus arctos horribilis in late spring. The stakes are high. My hopes are pinned on Rocky. Grizzlies have dominated Khutzeymateen Inlet since well before recorded history, attracted by the protein-rich sedge grass that grows in abundance here. For thousands of years, Indigenous Peoples accessed seasonal fishing and berry-picking camps in the estuary. Today, shore access is forbidden; this place belongs to the bears, whose daily wanderings stamp deep footprints into moss that dates back decades, if not millennia. Not only is Khutzeymateen Canada’s densest grizzly population, it is also the most protected.

That wasn’t always the case. In 1982, the area was slated for logging when wildlife biologist and conservationist icon Wayne McCrory received an anonymous package from Victoria, British Columbia, describing a unique valley on the northwest coast. That October, he landed in the inlet with bear researchers Stephen Herrero and Ralph Archibald. “We were so overwhelmed by the giant trees and the bears,” McCrory recalls. “We all came out dedicated to starting more research and a campaign to protect it.” The trio mapped the area, which contained the largest contiguous stand of old-growth Sitka spruce in the world. That year — long before the province ended grizzly-bear trophy hunting — a 300-kilometre (185-mile) hunting ban was established around the inlet, and the province commissioned a study that determined the area could not be logged without harming grizzlies.

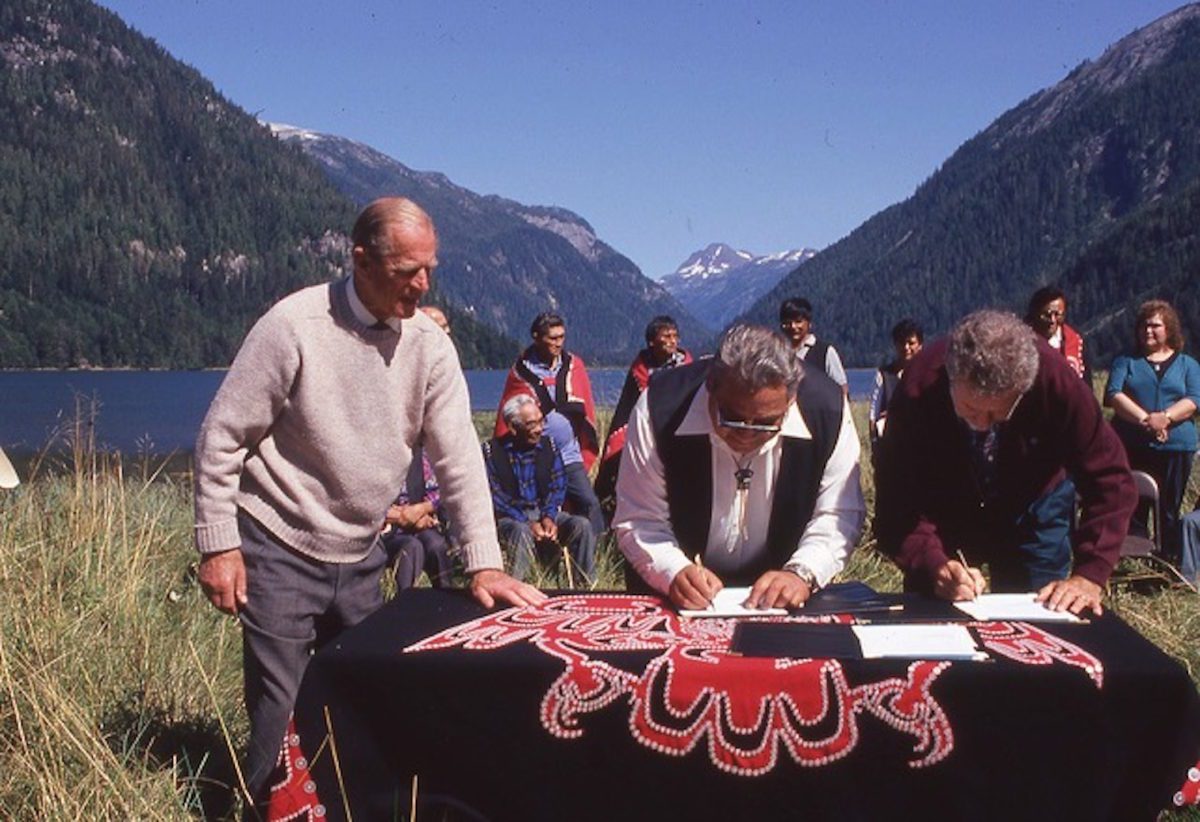

Over the next several years, researchers brought high-profile conservation groups, politicians, and film crews into the inlet and worked with the nearby Lax Kw’alaams First Nation to secure its protection. In 1994, during a signing ceremony in the estuary with local hereditary chiefs and Prince Philip, Khutzeymateen Grizzly Bear Sanctuary became a Class A Provincial Park. In 2008, a conservancy extended protection to the mouth of the inlet.

All of this may benefit bears in general, but it hasn’t helped Rocky. His injury may be the result of a tangle with another bear, but there’s a good chance it was sustained beyond the protected area. Although the hunting ban eliminated hundreds of grizzly deaths in British Columbia each year, dozens are still killed due to poaching, vehicle collisions, and government-sanctioned animal control. We watch as he rounds the next point and lurches to a halt. Our eyes dart from the hobbled grizzly to Hot Chocolate and not one but two suitors, and then we count: one, two, three . . . four. There are now four grizzlies in what is beginning to feel like a rather small bay. Under the cover of a cedar tree, Rocky drops submissively to his belly. Elmiligi lunges for the radio. “Holy smokes,” she radios back to the lodge. “It’s all going down.”

Khutzeymateen Wilderness Lodge is a floating piece of paradise moored near the mouth of the inlet. Started in the 1990s, it was grandfathered into the conservancy and purchased in 2015 by Jamie Hahn, a former BC Parks ranger for the area. Over the following winters, Hahn rebuilt the lodge from its floats — spruce logs, some nearly six feet in diameter — adding six guest rooms, a sauna, and a fire pit on the dock between its two buildings. From the communal dining area, guests can watch eagles soaring and the resident seal, Pomegranate, spying on them.

I am one of a handful of humans who will call this remote place home over the next three days. We arrived by float plane early this morning, hopping over the Coast Mountains on a 20-minute flight from Prince Rupert. Within minutes, we were aboard the Zodiac, which will take us twice a day on bear-viewing trips during our stay. It can feel more like bear voyeurism than bear viewing. “It’s like watching a soap opera, but with bears,” Elmiligi puts my thoughts into words as we watch Monty foraging alone in Tsamspanaknok Bay. The haggard bear digs for clams, using a talon-like claw to pry open the shells before slurping their contents. The hump that protrudes between his shoulder blades is especially pronounced after last season’s low salmon runs, and his coat hangs loosely from his hulking frame. In a region where a bear’s life expectancy can be in excess of 20 years, Elmiligi guesses Monty might be pushing 15, the years marked by scars on his face and neck.

If any bear knows how hard it can be to get a date around here, it’s Monty. He emerged, frail and bony, from hibernation in early May. Then he disappeared. For several days, local guides worried for the ailing bear, until he reappeared across the inlet, having swum 1.2 kilometres (0.75 miles) for the affections of Hot Chocolate. She ditched him for young Buddy. Tough times for a dominant boar whose impressive genitalia earned him a moniker from the swinging British comedy film The Full Monty.

Elmiligi has a long history with these bears. The biologist did her master’s research here more than a decade ago. Her work contributed to the province’s bear-viewing guidelines, such as keeping a minimum 75-metre (250 feet) distance and having a maximum of two boats view a bear at one time. She’s returned to find inspiration for her upcoming book, What Bears Teach Us, a collaboration with wildlife photographer John E. Marriott. “This book is really about how I was wrong so many times and how bears are really more complicated than we think,” she says. “With bears, it’s so hard to even find patterns because they’re all individuals. Bears do their own individual behaviour.” As a result, it is impossible to create blanket regulations that apply to every animal. Part of the sanctuary’s bear-management plan is training guides to recognize individual behaviours and respond accordingly.

Some bears, like Rocky, appear unconcerned about the boats that regularly drift nearby. Others are likely to take cover when the paparazzi come calling. It’s hard not to wonder how our presence is affecting these reclusive animals. In Elmiligi’s opinion, it’s not necessarily negative. “We’ve always had this assumption that a habituated bear is a bad thing, but that’s not always the case,” Elmeligi says. Bear viewing can, at times, help the bears, such as when females with cubs seek refuge from males by moving closer to the boats. “I think when it comes to the scientific world of bear biology, we’re really just beginning to acknowledge that this variation is a thing,” she says.

Several tour companies operate within the inlet, and the guides regularly swap bear gossip over the radio. They keep meticulous notes on who’s been seen where and with whom, passing the data on to BC Parks. Protecting the bears has become a joint effort between the operators, the province, and Indigenous People. “For us, it’s all about making sure the population’s not dropping and that we’re not having an impact,” Hahn says.

Khutzeymateen is located within the traditional territory of the Coast Tsimshian, specifically the Gitsi’is Tribe, and the inlet’s only other human inhabits are Norm Faithful and Al Maxwell, park rangers from nearby Lax Kw’alaams who have spent the last 25 summers at the K’tzim-a-deen Ranger Station. The floating interpretive centre sits at the sanctuary boundary and visitors are required to check in before entering the park. Only a few other tour operators — one offering day trips out of Prince Rupert and two working out of live-aboard sailboats that anchor here periodically — are allowed into the sanctuary. Even fewer have access to the estuary, where soaring granite walls tumble steeply into the inlet.

***

MEGAN BAKER, operations manager at Khutzeymateen Lodge, navigates the Zodiac carefully in the shallow estuary, steering around barely submerged beds of sedge. A grizzly with her young watches us warily from the shore, throwing concerned glances over her shoulder. Male grizzlies will kill cubs to bring a female into oestrus and mothers are on high alert. We cruise past Doze, who lifts his head drowsily, looking surprised that the grassy knoll where he drifted off has become a small island. We leave him to the rising tide as we venture deeper into the estuary.

The mouth of the Khutzeymateen River is just several boat widths across and no deeper than the height of an average adult. It moves lazily, almost imperceptibly. Sandy banks are overhung with greenery that is punctuated with yellow buttercups and pink salmonberry blossoms. The birthplace of the Khutzeymateen might just be the most peaceful place in the world. Baker kills the engine. For several seconds, we hang in silence, pendulous. The only sounds are the whistle of a varied thrush and a distant waterfall. Even as my body continues to feel the forward pull, the river gently begins to expel us. A crash in the nearby bushes breaks the reverie. Just beyond a row of Sitka spruce, a blonde grizzly, surprised to find us here, makes a noisy getaway.

Life appears to exist here much as it did thousands of years ago. Long after we leave, Monty will still be foraging in Tsamspanaknok Bay. Doze will still be sleeping peacefully in the sedge. Rocky will still be looking for love, and the last time I saw him, he was cautiously approaching Hot Chocolate as her new suitor lounged on a nearby log. The female climbed onto a rock and stared down the lame bear. Several minutes passed. I don’t know what that sow communicated, but Rocky lowered his head in defeat and waded into the water. After one last, longing glance, he swam off into the sunset. He was last seen making his way out of the inlet, beyond the protection of the sanctuary, to a world where grizzly hunting may be illegal, but trucks, chainsaws, and poachers persist.

Amanda Follett Hosgood is a Smithers, British Columbia-based freelance writer. While she loves the fuzzy four-legged creatures that roam the province’s northwest coast, she prefers to appreciate them from the safety of a boat.

Related Stories

Fernie Bears Love This Gin…But Not For The Reason You Might Think

Fernie Distillers has launched their first limited release seasonal product called 5th & Park Damson Gin made with…

Grizzly Snooze – The Backstory of a Classic Photo

Alberta resident and mountain lover Andrew Dole happened to be in the right place at the right time to snap this…

Ursus Urgentus – The Fate of BC’s Mighty Grizzly

British Columbia’s grizzly bears rule the peak of the food chain. But they’re being left to waste at the bottom of the…

Dancing With Grizzly Bear – An Interview with Ktunaxa Storyteller Joe Pierre

In this article, Aq’am Chief Joe Pierre describes in detail Qat’muk in the East Kootenays and what this sacred place…