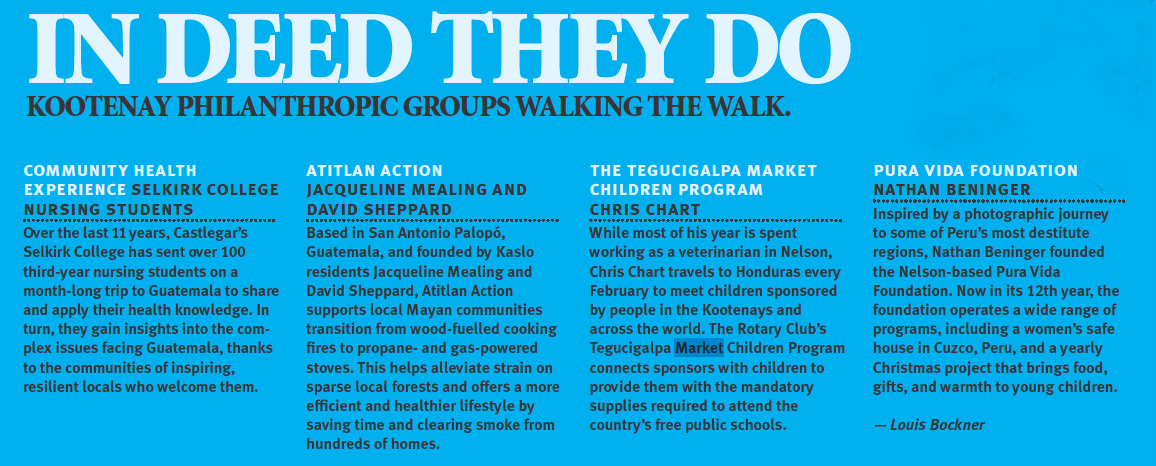

Every year, he trades in a life of solitude for service in a land of beauty with a violent past. Amid exploding molars, societal decay, and a Mayan microclimate, a British Columbia dentist searches for the root of it all. Story and photos by Louis Bockner.

MUSIC DRIFTS IN through the tiny cement room’s lone window, mingling with the high-pitched whine of a drill bit spinning 150,000 times per second and the nauseating smell of burning bone. Like most of the music played in Guatemala’s roughly 40,000 churches, it’s loud and dissonant—an unpolished mix of jarring piano, monotonous bass, nasal vocals, and clamorous drums. Yet in this moment, as dentist John Snively sits across from me, attempting to extract a rotting molar from a Mayan woman’s lower jaw while I suction the blood welling in her mouth, the discordant melody brings a sense of peace. It’s a distraction from the arduous task at hand, a brief remembrance of a world outside this stressful, stuffy room. Then, with a sickening crack!, the tooth shatters, and Snively mutters something about “Jesus mother” and “We’re in the jackpot now, bud.” I’m snapped from my reverie, once again oblivious to the music, transfixed by trying to remove the loose pieces of molar threatening to slip down our patient’s throat.

THE HIGHWAY CONNECTING southern Guatemala to its northwestern Ixil region is riddled with switchbacks and impossible grades. It’s March, the middle of verano, and the land is dry. Dusty fields planted with corn and beans fill the landscape between villages of cinder-block and adobe houses. The engineering feats of these roads are matched only by the bus drivers navigating them at speeds Bluebird school busses were not designed to achieve. On this particular bus, a giant decal declaring the vehicle a gift from God covers most of the windshield. It’s a bold act of blind faith.

I’m here, passing the blurred red and purple blooms of poinsettia and jacaranda trees, because my childhood dentist, Dr. Snively, invited me to accompany him as a dental assistant during a five-week, three-town tour of rural Guatemala. It’s his eighth year offering this volunteer service, and his second in the Ixil. I originally asked to document one of his excursions, but when his usual dental assistant backed out, I was promoted. I know nothing about dentistry and very little about what I’m getting myself into, which is probably a good thing. Sometimes the difference between naiveté and gusto is difficult to distinguish.

His operation functions on a minimal budget, and while he is partnering with local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in each of the three towns, funding comes from his own pocket, personal friends, fellow Rotary Club members, and a small Victoria, British Columbia-based organization called InnovativeCommunities.Org Foundation. Much of the smaller equipment and disposables, like anaesthetic, filling material, and gauze, are donated by fellow dentists. Some supplies are well used, some are expired, all are welcomed.

Guatemala’s Sierra de los Cuchumatanes rise to 2,400 metres (7,875 feet), their southern slopes are arid and barren, save for the Caribbean longleaf pine growing defiantly from depleted earth. But to the north, beyond the looming summits of the mountains, the reason Guatemala is known as the “land of eternal spring” becomes clear. The forests are lush and the scrubby pines are joined by oaks, alders, and sweet-smelling Monterey cypress. This is the microclimate beauty of the Ixil Community, which is named after the Mayan lineage and language linking its three municipalities of Santa María Nebaj, San Gaspar Chajul, and San Juan Cotzal.

Snively is waiting in Nebaj. He’s a slight man of 70 years with long white hair pulled back in a ponytail. A hawkish nose sits between clear blue eyes, and his gesticulating arms and hands seem a touch long for his body. Healthy and fit, his tanned skin whispers of a snowbird lifestyle that sees him spend seven months of the year at his cabin on the shores of Guatemala’s Lake Atitlán. The other months are spent overlooking Kootenay Lake in Queen’s Bay, British Columbia, where he’s lived since the 1980s. A self-proclaimed lake-gazing geezer, his affinity for being of service consistently lures him away from his love for solitude. “I have to warn you,” he says outside our hotel rooms. “There will be times during our work when I may make my anxieties, frustration, and anger known. Don’t take it personally. You’re just a rookie, and you don’t know anything about anything.”

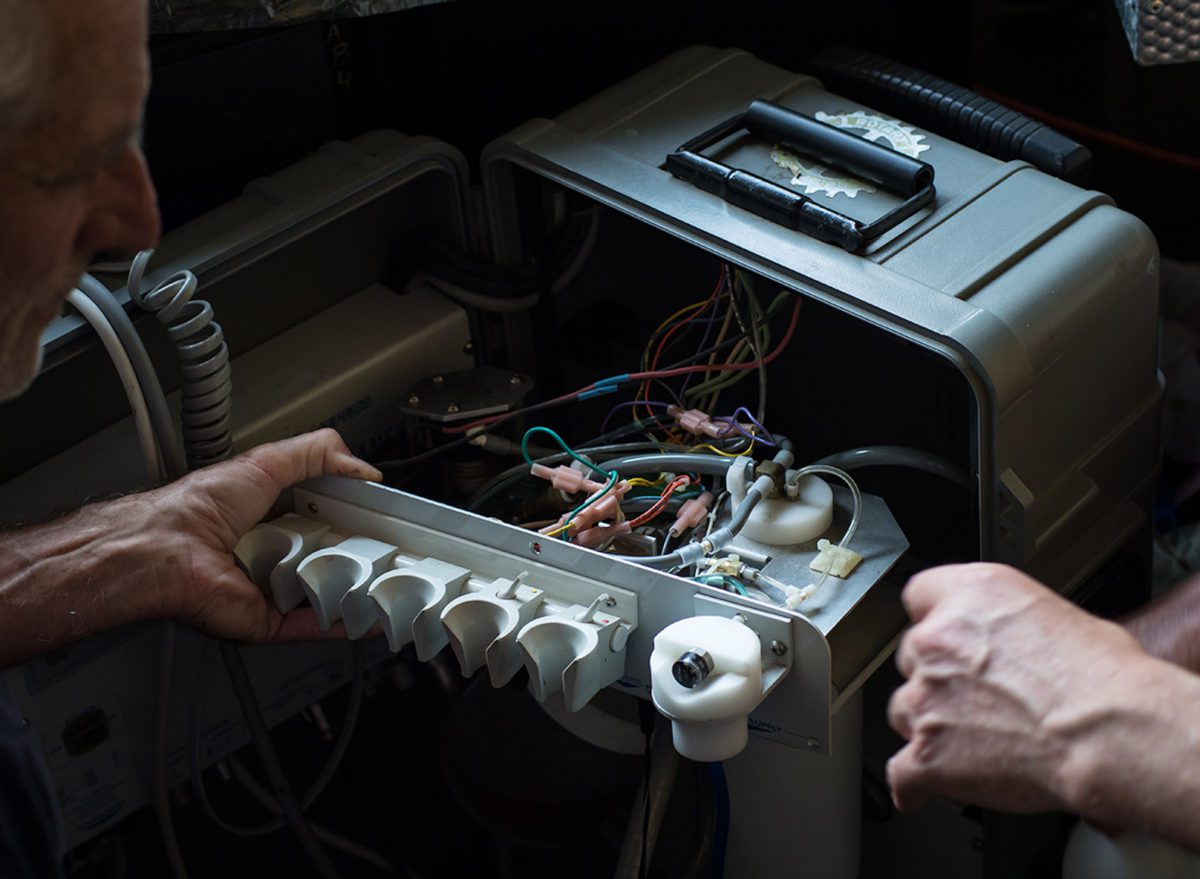

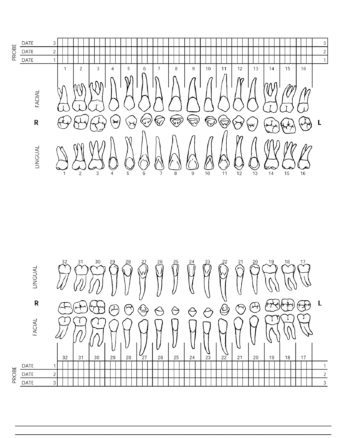

The next morning, we begin our daily commute to the nearby village of La Pista, where we’ll be working out of a small school called the Centro Explorativo. The clinic fits in the back of a pickup truck and can be functional in a room as small as three or four meters squared, which is more or less what we have. A folding dental chair and gooseneck light make up the centrepiece of the clinic, with two rolling office chairs on either side for Snively and I. A dozen totes are scattered around the room with labels like “sterilization,” “surgery,” and “electrical.” The main unit, called a Transport II, sits at the head of the patient chair. Originally designed for military use, it runs the vitals of our operation: drilling, cleaning, washing, air, and suction. The final pieces are two tables, where blood-covered tools are washed and run through cold and hot sterilization machines, and a set of drawers that contains all the equipment under my jurisdiction: filling materials in tubes and capsules; gauzes, cotton rolls, and Dri-angles; tools with names like towner, ball burnisher, cotton pliers, wedge pliers, and “the flat-bladed thing”; and little boxes with wooden wedges, celluloid strips, bond applicators, and other obscurities.

I’m snapped from my reverie, once again oblivious to the music, transfixed by trying to remove the loose pieces of molar threatening to slip down our patient’s throat.

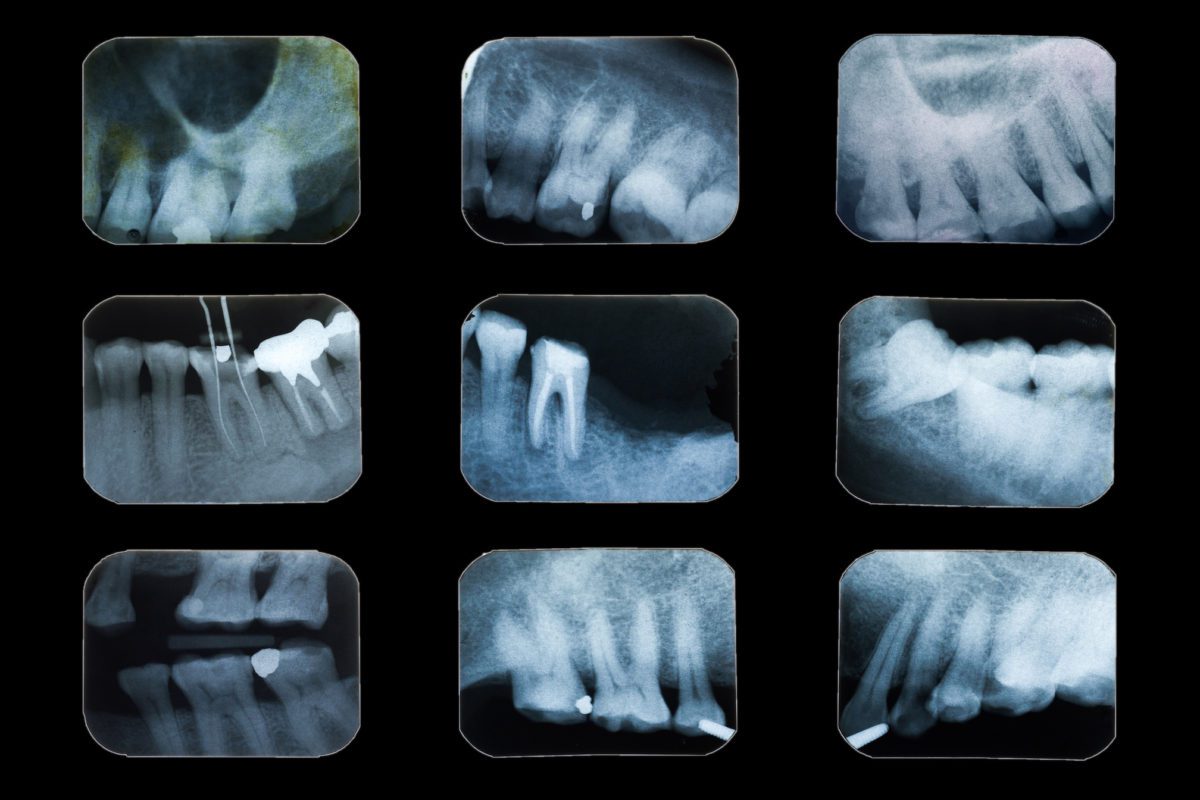

On our first day, 50 people wait patiently to be assessed and given an appointment in the following weeks. We are immediately plagued by technical difficulties. The handheld X-ray machine—one part galactic space gun and one part computer software—isn’t working, and the Transport II unit is acting up. Snively thinks it’s because of the solenoid. It’s happened before, and the unit is long overdue for a reboot back in the US. The suction, water, and air are weak, and though we can continue, the difficulty of our work will increase. Snively’s frustrated. I’m useless. But the show goes on. “Okay, you ready?” he asks.

“Yep, go ahead,” I reply, awaiting the list of dental jargon indicating the patient’s needs.

“We’ve got a one-six occlusal and a two-two DL. That stands for distal lingual. A 28 XO—that’ll be a toughie—and a 36, 37 occlusal and facial. We’re going to focus on that third quadrant and the extraction, so give me three units”

“Huh?”

“Sorry, I mean 45 minutes. One unit is 15 minutes.”

Our patients are predominantly Indigenous women and many wear trajes, the traditional dress of their culture. An intricately woven blouse, called a huipile, is tucked into a long red skirts, or cortes, a decorative belt, faja, headpiece, cinta, and ornate shawl, rebozo, complete the attire. Now, though, with improved roads connecting the region to the outer world, traditions are changing. In Nebaj’s main square, selfie-taking youth pair three-inch heels with their trajes, and teenagers skateboard on the church’s steps.

This shifting culture is visible in the mouths of our patients. Along with cell phones and stilettos, globalization has brought dietary changes to people uneducated about the dangers of processed foods and refined sugars. Pop is cheaper than bottled water, and a population that lived through decades of war has taken to these sugary indulgences with fervour. The insidious, threatening nature of poor diet and cheap foreign-made goods is harder to pinpoint than the immediacy of armed conflict. This, coupled with a lack of education around oral healthcare in rural communities due to systemic poverty, has created a population of people with decaying teeth, like the 16-year-old girl now lying between us.

Snively has partnered with Limitless Horizons, a local NGO focused on educating and empowering youth in a town where only three percent of children graduate high school. Of those that go through the Limitless Horizons program, the percentage climbs to 40.

“It’s obvious there’s no concept of ongoing care in this country,” Snively says as he assesses and lists our patient’s necessary fillings and surgeries. “Instead it’s a system of crisis management mostly triggered by pain. They have no concept of what healthy teeth look or feel like. There are people in this country who die of dental infections and no one knows that’s the reason. They go into a chronic state with their pain, and it gets dumbed down under layers of other issues from physical to social, but it’s there gnawing away.” After the young woman leaves the clinic, Snively adds, “That’s a point you could make in your article: there’s nothing more vital to our holistic health than the health of our mouths and teeth.”

The next morning, we begin our daily commute to the nearby village of La Pista, where we’ll be working out of a small school called the Centro Explorativo. The clinic fits in the back of a pickup truck and can be functional in a room as small as three or four meters squared, which is more or less what we have.

This lack of understanding is evident when assessing patients, many believing they “only need a cleaning.” Once Snively begins the exam, a long list of fillings and extractions is prescribed, of which we can only complete a handful. “It’s really hard for me to look in there and see everything that needs to be done and know I can’t do it,” he says about a young boy. “The deal is, we have to take out both of these molars. We have to explain to the mother that it will be hard on a five-year-old.” The translation is left to our local helper, Arturo, who is fluent in Ixil, Spanish, and English. Another man, Mark Arneson from Minnesota, has taken on sterilization—an important role, and one I’m grateful to avoid.

The next day, our first of treatment, the power goes out twice, and we are left with an anaesthetized patient and no way to continue. An hour later it returns and we resume, hoping it isn’t lost again in the middle of an operation. As the weeks pass, procedures blur together. Some last over an hour, sapping strength from Snively who visibly ages in front of me. While digging and drilling for infected roots or attempting difficult reconstructions, he is effectively alone, the patient’s well-being firmly in his hands. At the end of the day, he physically shuts down for a time. Eyes closed, breath slow, recuperating, hanging on. In those moments, he transforms from ageless to ancient.

The Transport II continues to falter. The water, air, and suction becoming weaker as the days pass. Snively is concerned and thinks we may have to pack it in, a disappointing prospect considering the effort and money that’s gone into the trip. “You know,” I say one afternoon, “when the solenoid on my Volkswagen van acts up, I bang it with a hammer.” Two days later Snively is using a screwdriver and stick to hit the small ailing electrical box. “I feel like we’re in the stage of life where we need to try weird stuff,” he says smiling. “Welcome to Guatemala. It’s pretty much all you can say.”

AFTER TWO WEEKS in Nebaj we move north to Chajul, the Ixil’s largest municipality in terms of land mass. The town itself is a collection of adobe houses with ceramic-tile roofs, which are quickly being replaced with ones made of earthquake-resistant cement blocks topped with corrugated metal. As with most Guatemalan towns, Chajul’s layout revolves around a large Catholic church and plaza built centuries ago by the invading Spanish. Here in Chajul, as in Nebaj, the church and central park have recently been renovated in an effort to mute memories of the civil war that ravaged Guatemala from 1960 to 1996. A time many simply call la violencia.

The Ixil, thanks to its remote, mountainous nature, became a stronghold for leftist guerrilla groups that took up arms in the 1970s to resist the US- and Israel-backed military government. In 1979, the army was sent into the region under the banner Operacion Ixil. Its aim was twofold: destroy the guerrillas and paralyze their support base through fear-inducing brutality. Over the next four years, a “scorched earth” campaign was carried out, during which 114 known massacres occurred in Indigenous villages. The military took over towns, killing and torturing anyone suspected of supporting the guerrillas and forcing others to join their notorious death squads. Snipers settled into the bell towers of Chajul’s church and executions took place in the plaza outside. Unofficial numbers put the death toll at 20,000—out of the 200,000 killed in Guatemala during the war.

In 1994, the Oslo Accords called for a commission to objectively look at the human rights violations that took place during the war. The ensuing report, Guatemala: Memory of Silence, was released five years later. Ninety-three percent of all incidents of torture, death, and disappearances were assigned to military commissioners and right-wing death squads. Of the 658 documented massacres, 626 were attributed to state forces, and 83 percent of the war’s confirmed dead were Indigenous. The report also declared that state-directed attacks in certain Indigenous communities, including the Maya Ixil in Nebaj and Cotzal, constituted genocide. The trials of those responsible for orchestrating these attacks are still ongoing.

Due to a post-war baby boom, Guatemala’s population, almost half of which is under the age of 19, is looking to the future. In Chajul, it’s these youth who fill our patient chair

SNIVELY AND I are both suffering from head colds, and the days become long. Hot breath stagnates under my surgical mask and coughing fits are suppressed during procedures. The state of our young patients’ oral health is heart-wrenching. Infections are scraped from caverns where molars were pulled, rotten teeth are resurrected with difficult fillings, and problem after problem is wrestled with. In moments of stress, when our world shrinks to a single task, Snively falls back on a career encompassing four decades, two continents, and three retirements. His first retirement came in 1974, after only three years of working. Friends who chose travel over university returned home to Hamilton, Ontario, with wide eyes and tall tales, so he sold his Datsun 240Z, bought a van, and set off for Central America. It was this trip that introduced him to Guatemala’s rich culture and sparked a lifelong love affair with the landscape, its people, and their textiles.

“It’s obvious there’s no concept of ongoing care in this country,” Snively says as he assesses and lists our patient’s necessary fillings and surgeries. “Instead it’s a system of crisis management mostly triggered by pain.

In the early 1980s, after working as a dentist for the Department of Northern Health and Welfare in Canada’s Arctic and earning a degree in holistic nutrition and massage, he moved to Nelson, British Columbia, hoping to become a massage therapist. Instead, he was offered the keys to an eclectic, progressive dental practice where he again fell in love with his craft. In the following decade, he never took a sick day, moved the office onto Nelson’s main drag, Baker Street, and became known as a compassionate doctor with a deep understanding of the relationship between dental and holistic health. He was the first dentist in Nelson to remove mercury amalgam fillings and once did a work exchange with my mother for a pair of home-knitted mittens. He’s that kind of guy. One who believes that “service above self can only occur when the giving becomes the receiving.” In 1998, ready for his final semi-retirement, he sold the practice, and it wasn’t until 2010, while on another trip to Guatemala, that he began extracting teeth in villages around Lake Atitlán. His passion for service reignited, he sought funding through the Rotary Club and Innovative Communities to purchase the $50,000 clinic we are now moving to Chel, an end-of-the-road town three hours north of Chajul. The final stop on our journey.

After our assessment day, we are both overwhelmed. The mouths in this rural village are the worst we’ve seen, and for the first time the smell of rot seeps through my protective mask and extractions begin to outnumber fillings. Here, the short-term nature of our work becomes clear. While we’re alleviating immediate suffering, the roots of these issues run deep. Rebuilding and pulling teeth feels like bandaging a body that’s internally bleeding. The trouble is, the people and corporations that fund NGOs and local initiatives are always more inclined to invest in bricks and mortar than human capability, leading to a reliance on foreigners like Snively—and a return to the status quo when they cease working. There’s no lack of resilient, hardworking, intelligent people in Guatemala, but there is a lack of opportunity and support for them to dictate their own future.

That evening the discussion turns to the act of service, the difficulty of addressing these systemic problems at their source, and the importance of addressing the immediate need. Michael Ewens, our host, has lived in Chel permanently for four years and heads a small NGO called the Ripple Effect, dedicated to providing permaculture education and building water systems. Currently he is forming an all-local board for the organization so the work can continue without him. “Everything I do here is a Band-Aid,” he says, “but it’s a good Band-Aid, and I’ll do it until the day I die.”

“Well that’s the same as us,” says Snively from the other side of the fire. “Everything we do is only a temporary fix.”

“But you’re making a significant difference in their daily lives,” Ewens replies. “You can’t forget that.”

The next afternoon, while treating our last patient of the day, the main unit emits a bang and then a hiss. After limping our way through a difficult extraction, it’s clear our days are numbered. With no water or air and only the slightest suction, fillings are nearly impossible and extractions bring risks to patients. We decide to finish tomorrow’s surgeries and cancel the remaining three days.

Everything is packed into the back of Ewen’s Toyota by 2 p.m. on Good Friday. After performing 85 extractions and 253 fillings on 101 people over 20 clinical days, it’s a relief. We are exhausted, and it’s hard to say whether Snively will initiate another tour of duty. “There are times when I think I could never do this again,” he says lying in the river that winds by Ewen’s farm. “Then after, when it’s all over, I see again how badly they need this service, that it’s a privilege to visit a place and do this kind of work. The truth is I’m just getting too damn old for this.”

At 27, I sympathize. Soaking in the cool water I feel run-down and depleted. My body is covered in bug bites, I’ve lost 15 pounds, and I’ve seen enough tooth decay to last me a lifetime. Yet, somehow, I’m already envisioning a return. The genuine gratitude of the people, their vibrant culture, and the eternally green mist-covered mountains have moved me. Soon the strain and stress will fade and other memories will shine through. The stoic little girl who fell asleep as we repaired her molar, the gracious families who invited us into their homes for lunch, the smiles of children playing on smoky cobblestone streets, and the rhythmic clapping of skilled hands preparing fresh tortillas for a new day.

Although Louis Bockner now knows more about dental procedures and anatomy than any civilian should, he won’t be quitting his day jobs of writing articles and snapping pictures any time soon. He will, however, brush and floss more diligently than ever.

Related Stories

STAND movie hits BC in early May

From our Friends Anthony Bonello of b4apres Media, and Nicolas Teichrob, photographer comes the cinematic premier of…

Creaking Tree String Quartet touring BC

Two time Juno nominees, The Creaking Tree String Quartet are coming to British Columbia to promote there fourth Album.…

Cool New Video by Nelson BC’s Best Western Hotel

The world of the webisode gets funner by the day. This new piece by the local Nelson family that runs the town's Best…

New BC Bike Race Movie Lands Today

BC Bike Race has released its third feature film, "The Journey," documenting the 2017 event. Watch it below. Director,…

3 BC Cities Named World’s Best For Rock Climbing

In a recent article by Carlo Alcos on the Matador Network travel site, three cities in British Columbia and one in…