A skier on the brink of making it. A young climber with aspirations of international competition. An emerging photographer with a career in sight. A teenage snowboarder with powder fields of opportunity underfoot. Meet the next generation of mountain-sports athletes, guides, instructors, and storytellers. These are their dreams and their challenges. By Jayme Moye.

Lauren Powers was 10 years old when she made a life-altering declaration: “Mom, I need a snowboard.” Powers, now 29, remembers that precipitating moment of self-awareness clearly. It was 1999, and she was standing atop an intermediate run at the local ski hill in Kitchener, Ontario, where she grew up. As she peered over the edge, an unexpected thought detonated in her brain: I hate skiing. In hindsight, Powers thinks it was the body position, the sensation of pointing her skis straight downhill that she didn’t like. “I needed to be in a different direction,” she says. Powers got her first snowboard that Christmas, and it quickly became her favourite possession.

After high school, Powers moved to Banff, Alberta, so she could snowboard in the big mountains of the West. “All my friends’ moms thought I was going to ruin my life,” she says. She didn’t let the naysayers deter her. Powers understood life in her hometown was linear: high school, university or college, a good job, marriage, and kids. Deviating from those expectations was frowned upon. But her own parents had met in Banff in the 1980s while they were cleaning rooms at the Fairmont Banff Springs resort and she thought they had turned out just fine. When she was 15, her parents brought her and her siblings to Banff for a vacation, back to where it all started for them, and Powers felt strongly that the town was the right starting place for her too. Snowboarding in the Rocky Mountains was something she had to do. It wasn’t even a choice.

SAM KUCH, 22, GREW UP in Nelson, British Columbia, in the Selkirk Mountains, where it is more common and accepted to follow a mountain-sports calling. His parents moved to the area from the prairies when he was one, and Kuch, his two siblings, and his parents all became expert skiers together. At 13, Kuch joined Whitewater Ski Resort’s competitive freeride team. His wildly successful youth career culminated in 2016 with a first-place finish at the IFSA North American Junior Freeride Championship at age 18. But when Kuch began competing as an adult the very next season, he failed to make the Canadian national team, crashing in three out of four qualifying events.

Hoping for a better outcome in 2018, and with the full support of his family, Kuch tried again, only to crash out of his season-opening competition. His confidence plummeted. He had hoped to follow in the footsteps of friend and mentor Trace Cooke, another Nelson native who’d placed first in the IFSA North American Junior Freeride Championship in 2013 when he was 18. Cooke had gone on to make the national team the following season and compete on the professional Freeride World Tour. But with Kuch’s disappointing first season as an adult and now his second season off to the worst-possible start, he became so discouraged that he pulled out of competing the rest of the year and began researching post-secondary education. He decided to enter a power-line technician program. Kuch had completed a training course when local photographer Bryan Ralph texted, asking him to show a small group of Olympians and professional skiers around Whitewater. “Sure,” Kuch texted back.

DURING HER FIRST SEASON snowboarding in Banff, Powers supported herself by cleaning rooms at the Fairmont Banff Springs resort, like her parents. She also began teaching herself photography, which felt like a natural extension of her reverence for mountain scenery. She knew she eventually wanted a career, so she completed a two-year program in environmental management, but she fell for an Aussie and moved to Australia before using her diploma. Living abroad catalyzed her curiosity about the world and further stoked her interest in photography, but she wasn’t getting closer to a viable career. Powers returned to Canada to study geography at the University of British Columbia in Kelowna. She lasted one year. “I guess I just loved snowboarding too much,” she says.

In 2013, Powers moved back to a mountain town, this time in the Kootenays, and back to working in the service industry. As a hostess for Snowwater Heliskiing, she learned about a snowboarding job she hadn’t known existed: tail guide. Unlike lead ski guides, who must undertake an extensive and expensive multi-year certification program through the American Mountain Guides Association (AMGA), an aspiring tail guide assists lead guides and can earn certification through the Canadian Ski Guide Association & Institute in a single season. Powers landed her first tail-guiding position in 2015 with Big Red Cats in Rossland, British Columbia. She wanted to work the summers too, so she obtained a hiking-guide certification and was hired by Mountain Trek, a retreat centre and spa in Ainsworth, British Columbia.

While she settled into a guiding career, Powers continued to further her photography skills. Soon she was shooting clients for Big Red Cats in addition to guiding there. In 2017, she started getting jobs in Nelson; she photographed Soulines, a multi-day backcountry snowboarding and skiing event, as well as the Pow Gals backcountry ski clinics. The following season, Baldface Lodge hired her to shoot clients skiing and snowboarding in the backcountry. Between guiding and on-mountain photography, Powers felt she had found her path.

THE PROFESSIONAL SKIERS Kuch was tasked with showing around the mountain were filming with Forecast ski magazine for a web series called Beyond the Powder Highway. Kuch took them to his favourite zone at Whitewater, an area just out of bounds known as Trash Chutes. He pointed to the ambitious line he intended to ski: a 200-metre (656-foot) open shot filled with hundreds of snow pillows. Thanks to the group’s friendliness and enthusiasm, the intimidation he felt in the presence of industry giants, like Stan Rey, faded. Kuch felt confident on his home turf. He punctuated his first run with a 360-degree rotation off a sizable cliff. As his companions hooted their approval from the top of the run, the doubts — and crashes — that had been plaguing Kuch since his foray into adult-level freeskiing competition suddenly vanished. Filming, even with elite athletes, was fun to him, like a shred day with friends. As a result, he had one of the greatest ski days of his life, and it was all captured on camera. Kuch’s performance earned him significant footage in the film and the Discovery of the Year award at the 2018 IF3 (International Freeski Film Festival). “From there, everything just kind of skyrocketed,” he says.

For the 2018–2019 season, Kuch was employed nearly full-time as a professional freeskier. He shot with Blank Collective Films, Rey’s new company based in Whistler, British Columbia, and Colorado-based Matchstick Productions, arguably the top ski-movie producer in North America. Head, a company that had been supporting Kuch with gear and apparel since 2016, promoted him to its international team, the top tier in sponsorship, and he shot in destinations like the Monashee Mountains and Mount Baker, Washington. By the end of the season, Kuch sealed a national sponsorship with The North Face.

AFTER THE THRILL of breaking into the outdoor industry, Powers confronted some hard truths: she could barely afford rent and she was run down. “I was back-to-back guiding for four years — that’s eight seasons — so 10 months out of the year wearing a backpack,” Powers says. She began to worry that her line of work was neither financially nor physically viable.

Charles Chesbro can relate. The 25-year-old moved west from Atlanta, Georgia, in 2017 to work as a ski instructor at Schweitzer Mountain Resort in Sandpoint, Idaho. He’d felt the call of the mountains since his youth, propelled by adventure-oriented summer camps and family ski vacations. But Chesbro quickly realized he couldn’t make enough money to live as a ski instructor, so he found additional work teaching an outdoor physical-education class at the local high school. In the summer, he works as a wildland firefighter. Still, Chesbro can’t afford the basics, like American health-care and mountain-town rent. He lives in his van, which is parked inside a friend’s garage in Sandpoint.

Charles Chesbro can relate. The 25-year-old moved west from Atlanta, Georgia, in 2017 to work as a ski instructor at Schweitzer Mountain Resort in Sandpoint, Idaho. He’d felt the call of the mountains since his youth, propelled by adventure-oriented summer camps and family ski vacations. But Chesbro quickly realized he couldn’t make enough money to live as a ski instructor, so he found additional work teaching an outdoor physical-education class at the local high school. In the summer, he works as a wildland firefighter. Still, Chesbro can’t afford the basics, like American health-care and mountain-town rent. He lives in his van, which is parked inside a friend’s garage in Sandpoint.

Chesboro, who holds a bachelor’s degree in outdoor education from Georgia University, hopes he can find better-paying, year-round work in his field by increasing his education. He’s considering a master’s degree in business or behavioural research that will open doors in wilderness therapy, a growing field that’s been effective in treating American veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. “Working in outdoor recreation is really fun,” says Chesboro “but it hasn’t been very lucrative for me.”

A similar thought occurred to Powers. Through her time at Mountain Trek, she realized she could make more money and perhaps a more significant impact by working on the therapeutic side of mountain sports. She’s currently completing a two-year program in massage therapy. With it, Powers wants to secure year-round employment that’s easier on her body than guiding. She hopes the shift will enable her to snowboard as she ages, while offering enough freedom to continue pursuing on-mountain photography.

Kuch is also dealing with the stress of seasonal employment. When he was trying to break into the adult competition scene, he had a relatively secure solution: in the summer, he worked in roofing or carpentry and he was laid off when the cold weather moved in, allowing him to focus exclusively on skiing while receiving a bi-monthly cheque through employment insurance. It wasn’t as much money as he made in the summer, but it was enough that he could afford to live on his own in something other than a van. But now that he’s making money in film through the winter, he no longer qualifies for employment insurance. He hopes to increase his film work so he can ski year-round. Kuch’s more immediate concern is Instagram. He grew up with the technology so he understands its functionality, but the challenge is meeting his sponsors’ expectations to increase his following and their exposure, in a way that feels authentic. “I hate feeling like a cheeseball putting out goofy posts,” he says. He also struggles to balance all the “indoor” work he has to do — the business side of being a professional mountain athlete — from answering emails to learning how to interact with brands to acquiring and maintaining sponsorships. “It was a reality shock,” he says.

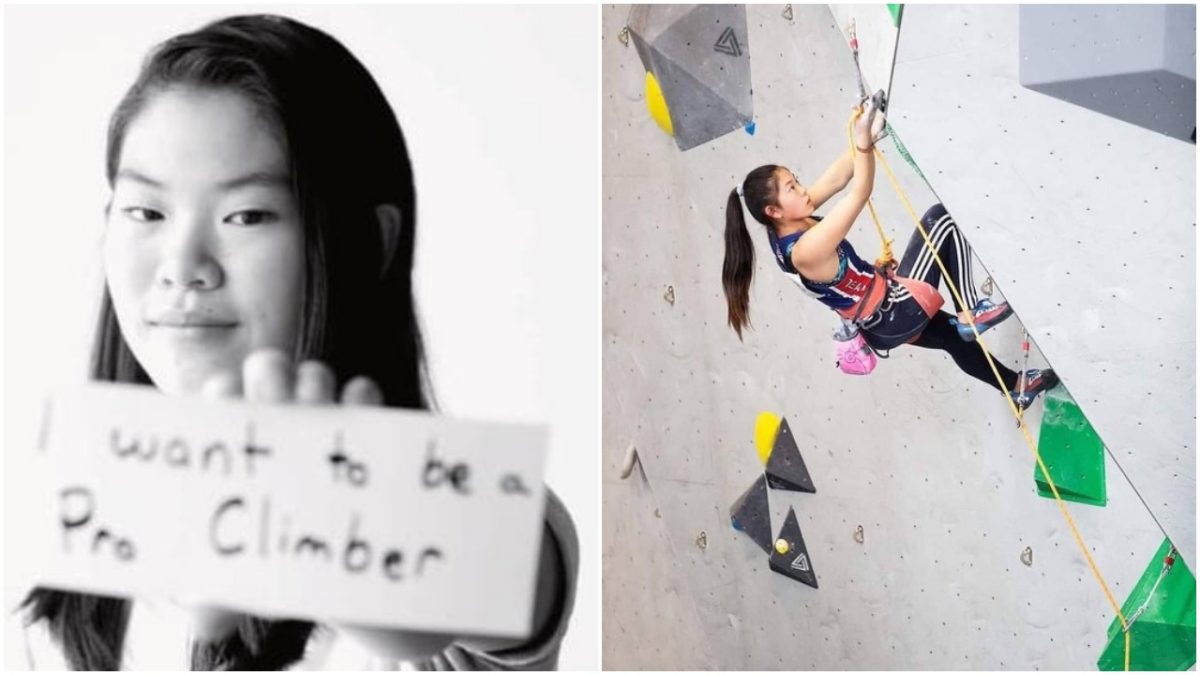

FOR MOUNTAIN-SPORT UP-AND-COMERS who are still young enough to be living at home, dreams are less concrete and struggles are more about time than money. Fifteen-year-old high-school student Tula Sherkat knows she wants to go to university, but she isn’t sure how it will fit in with her fledgling competitive rock-climbing career. Sherkat has been competing — typically inside climbing gyms — since she was eight. She had her international breakout this past February, when she placed second in her age division at the Youth Boulder Nationals in Montreal, earning her an invitation to try out for Canada’s Youth National Team to compete at the International Federation of Sport Climbing Youth World Championships in Arco, Italy. Sherkat made the national team, and in August she placed 49th out of 87 competitors in her category. Her next international competition will be in November at the Pan- American Championships in Ibarra, Ecuador.

Sherkat’s training season roughly mirrors the school year, starting in the fall and continuing through the end of spring. She juggles training four days a week and travelling to about a dozen competitions a year in Canada and the US with a straight- A average, piano lessons, and performance dance. Now that she’s competing at the world level, she’s added summertime training and competition. In her short life, Sherkat has lived in Victoria and Squamish, British Columbia; Canmore, Alberta; and most recently Nelson, as her parents scramble to support her and her older brother’s competitive climbing ambitions. Sherkat says she gets tired of the travelling but is determined to make the podium in Ecuador. She can always slack off on piano. Or maybe quit dance. One thing she says with certainty: “I’m going to be a climber until I’m too old to get out of the house anymore.”

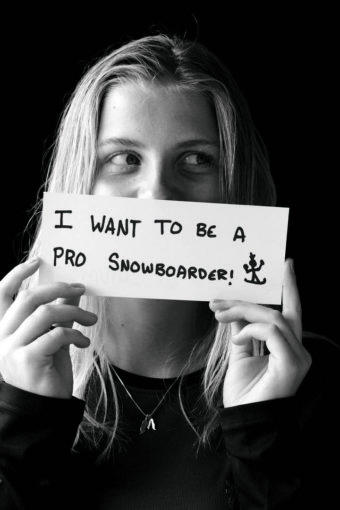

Estelle Pensiero, 16, echoes that sentiment, but for her it’s about snowboarding. The high-school student can’t imagine life without it. She grew up in a backcountry ski-and-snowboard lodge; her parents were in the process of building Baldface Lodge and living in one of its chalets when she was born. Before Pensiero had a driver’s license, she’d won the Kootenay Coldsmoke Slopestyle competition for her age category and the JLA Banked Slalom at California’s Mammoth Mountain. At Mammoth in 2019, she also entered the boys’ division “just to see how I stacked up” and took third place.

Pensiero is not yet sure how to monetize her passion, but she has some ideas. She idolizes snowboarding superstar and Baldface Lodge guide Robin Van Gyn for her snowboarding film career and also for pursuing the demanding AMGA ski-guiding certification. Pensiero has already completed her Avalanche Skills Training 1 and 2 and hopes to have her tail-guide requirements met by the time she graduates from high school so she can “start getting paid to snowboard.” She has also nabbed her first sponsors. In 2018, Austin Smith took a video of Pensiero ripping down a ridgeline at Baldface, and it garnered more than 32,000 views on his Instagram account and was widely shared on social media. Afterward, Pensiero signed on with Vans, Dakine, and Lib Tech for what are known as grassroots sponsorships, which are entry-level sponsorships that provide gear and apparel in exchange for social-media content and other forms of marketing. In 2019, Pensiero experienced some of her first reality checks. Like when she landed on her face attempting her first backflip. And she balked at riding the big lines on a heli-skiing trip with her dad, Van Gyn, and snowboarding legend Travis Rice. “It made me realize how good they are,” Pensiero says.

Time will tell whether snowboarding stardom and financial stability will be attainable for Pensiero. She also has the option of the family business. As the oldest of four children and the most enthusiastic about snow sports, she’s the logical choice to take over Baldface Lodge. “I’d definitely have to go to college for that,” she says, “and right now I just want to snowboard.”

Pensiero’s perspective is reminiscent of how Powers felt at that age. Powers recalls that whenever she was feeling lost or uncertain about the future, she asked herself, “Well, what do you love?” The answer was always “snowboarding,” so Powers steered herself accordingly. “Snowboarding has gotten me further than anything else in life,” she says. “I don’t know how many people get to say that.”

Freelance writer Jayme Moye is the 2019 recipient of the Keith Bellows Award for Excellence in Travel Journalism, which honours the longtime editor-in-chief of National Geographic Traveler and recognizes a writer whose work embodies the power of travel to teach and transform.

Related Stories

Why The West Kootenay Bouldering Scene Is Blowing Up

On the heels of the announcement that Ladybird Creek Bouldering area in the Slocan Valley is now a BC Recreation Site,…