Well over a century ago, under the arc of the Illecillewaet Glacier, Mary Vaux broke first ground for female mountaineers and scientists, boldly stepping into the male-dominated mountains. A new film documents her life and legacy. By Cassidy Randall.

“Legends throughout the world tell us that it is in that moment of uncertainty that the call to adventure comes. – Mary Vaux

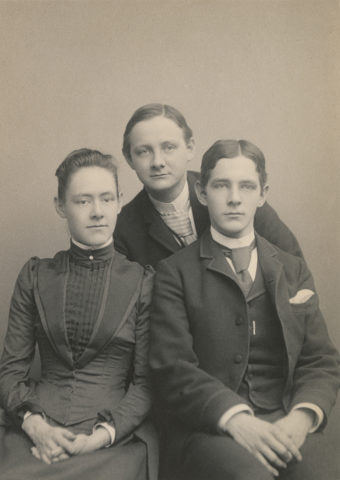

In 2016, Revelstoke-based filmmaker Agathe Bernard stumbled on a grainy black-and-white photograph of a woman in a Victorian dress carrying an ice ax, dwarfed by the massive ice around her. That single captivating image sent Bernard on a hunt to discover the story behind it, one that would define the next two years of her life.

The woman in the photograph was Mary Vaux, and she’s standing by the Illecillewaet Glacier on Rogers Pass, an hour’s drive east of Bernard’s home. The date was 1910 and Vaux, who was 50 years old at the time, was wearing full, heavy skirts, a high-collared white shirt and a full-brimmed hat. She had mountaineered up the pass and arrived at the toe of the mighty glacier, a 22-metre-high wall of dirty ice with cracks of luminescent blue. She dropped her heavy climbing tools, shoved her skirts aside, and painted a line in tar on a rock at the edge of the ice. With that mark, she became the first person in North America to study glacial recession and solidified her role as one of the few women at that time who were breaking gender barriers in both the science and mountaineering worlds.

https://vimeo.com/287317098

Vaux racked up a long line of alpine achievements in an age when cultural norms meant most women married young and were relegated to the roles of motherhood and housekeeping. In 1900, she became the first woman to reach a peak over 3,000 metres (10,000 feet) in Canada when she summited Mount Stephen. For that expedition she wore pants, which were frowned upon for women, but just before celebrating her accomplishment, upon her return to the base of the mountain, she ducked behind a building to change into a dress. She was also the first white woman to set foot in Yoho National Park, and she and her friend Mary Schaffer were the first women to explore the Nakimu Caves in Glacier National Park.

A Philadelphia native, Vaux first discovered the Canadian Rockies in 1887. She travelled via the Canadian Pacific Railway, which had just been completed two years earlier, with her brothers and father, where they stayed at Glacier House on the summit of Rogers Pass in its inaugural year. It was on that trip that she first laid eyes on the glacier, which became a lifelong obsession. She began studying the Illecillewaet Glacier, alongside her brother William, by taking annual photographs from fixed points marked in tar or metal plates to record recession. After William’s death, Vaux decided to continue the studies on her own, a revolutionary act whether she intended it or not: she was a woman in charge of her own research and the mountaineering required to undertake it. It wasn’t long, however, before she became a respected member of both the science and alpine communities; she hosted regular slideshows and had articles published in the Canadian Alpine Journal.

Vaux bucked other social norms, remaining single until the age of 55 and childless all her life. When she did marry, it was to Dr. Charles Walcott, a scientist at the Smithsonian studying the Burgess Shale near Field, British Columbia. It’s worth noting that when they took their honeymoon on Rogers Pass to make Vaux’s yearly pilgrimage to the Illecillewaet, he was her assistant during that trip.

In 1906, six years after she changed into a dress at the base of Mount Stephen, Vaux lent her energy as a founding member of the Alpine Club of Canada to ensure “the conservation and preservation of the Canadian wilderness, and unlike its British predecessor, to promote equality between women and men within mountaineering and climbing,” wrote author Marjorie G. Jones in her book Life and Times of Mary Vaux Walcott. And it appears she had an impact. The next year, the Club shared the following about wearing skirts for mountaineering: “No lady climbing, who wears skirts, will be allowed to take a place on a rope, as they are a distinct source of danger to the entire party. Knickerbockers or bloomers with puttees or gaiters and a sweater will be found serviceable and safe.”

After Agathe Bernard saw Vaux’s photo at the glacier and discovered her legacy, an idea took hold in her mind: she would hunt for that old line marked in tar so many years ago and recreate Vaux’s experience. The result is the short documentary Carving Landscapes, which tracks her career after her brother’s death and details the challenges she faced. Bernard interviews modern glaciologist Dr. Alison Criscitiello about Vaux’s impact on the academic world, and the visuals of the ice’s magnitude, as an actress in a Victorian-era dress climbs the glacier with an ice axe, are stunning. It’s a sweeping project that pays homage to the rebellious Vaux and documents the retreat of the once-formidable Illecillewaet Glacier over the last 130 years. But more than that, the film celebrates how Vaux and early pioneers like her continue to inspire women to push limits in the worlds of science and alpinism.

Related Stories

KAVU Canada Lands First in Fernie

On March 22, 2014 KAVU & Elevation Showcase Presents KAVU Canada. KAVU athletes and KAVU staff will be dropping…

Meet Hickshow Productions

Hickshow Productions is as grassroots as it gets: they're Slocan Valley sleddin' souls who have a scene or two to…

Surf Canada Now Ranked Top 10 In The World

Thanks to an historic showing at the World Surfing Games in Japan, the Surf Canada team is now ranked 10th overall in…