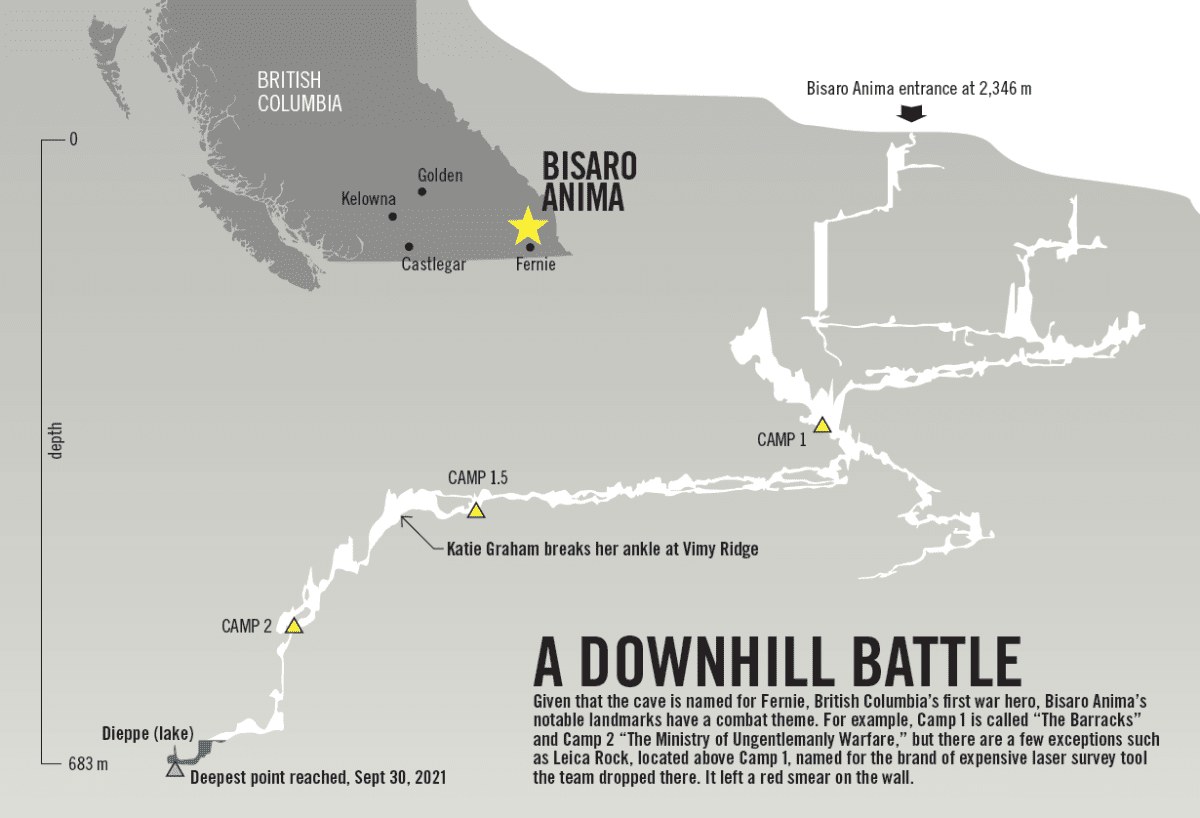

A look inside 10 years of discovery and determination in Bisaro Anima, the 683-metre-deep cave near Fernie, British Columbia. By Katie Graham

Deep in the don’t-screw-up zone, I screwed up. Half a kilometre below the surface, in the pitch-black belly of the Bisaro Anima cave, my anxious mind got the better of me. The members of this 2019 expedition and I were behind schedule, so I picked up a heavier haul bag than I’d normally carry and rushed to get us back on track. The glare of my headlamp showed two guys in my path, so I went around them onto an unstable slope. Basketball-sized rocks started moving. I tried to regain my footing, grasping for anything solid, but I was already over the edge — falling two metres with 24 extra kilograms on my back. I crumpled in pain when I tried to stand; something was wrong with my ankle. Scuba diving the lake 650 metres deep in the cave — which had preoccupied my thoughts for so long — wasn’t going to happen. Humbled, I focused on being as little of a liability to the others as possible. The pain eventually became tolerable, so I crawled along and climbed a rope with one foot to escape the cave. Three days later I saw the sun.

In 2012, I teamed up with nine other cavers to splurge on a helicopter ride to the Mt. Bisaro Plateau located about 10 kilometres (six miles) north of Fernie, British Columbia. The area is a playground of caves; they’re everywhere, but as we soon discovered, most are short and choked with rock, snow, or ice. Only one hole showed potential. Standing at the precipice of the deep drop-off, we peered over and threw a rock down the shaft. A four-second silence was followed by a massive boom reverberating from below. We looked at each other with huge eyes, “Holy shit, that’s deep!” This chasm, Bisaro Amina, soon became an obsession fuelled by awe and curiosity.

The next few years were exciting, with annual trips to Bisaro Anima. Long days were spent rigging and mapping the vertical cave. It took nine hours to commute from the mouth of the cave to our exploration areas, and our quads and shoulders were fatigued after days of going up and down ropes. In 2015, we set up the first of three underground cave camps: four hammocks in a rocky alcove dubbed “The Barracks,” where we stashed gear that allowed for a flurry of exploration.

We started doing winter trips because the water level is lower when the mountaintop is frozen, while the cave is the same temperature year-round. We did hydrological studies to understand the water flow in the cave, 3D mapped the mountain’s surface with a drone, and climbed many avens (vertical shafts) looking for shortcuts to the surface. We followed canyons and waterfalls deep in the cave and were amazed to find a lake more than half a kilometre down in the middle of the mountain. The only way to continue seemed to be underwater. In 2018, I dived the lake and proved Bisaro Anima is the deepest known cave in Canada, but damaged gear prevented me from going very far. In 2019, I broke my ankle while hauling gear in, and 2020 was cancelled due to COVID-19. In 2021, I finally got a second chance.

After adjusting my gear and nodding to my teammates, who all have their headlamps turned on me, I enter the water of the underground lake. Liquid laps over my head and its cold embrace envelops me. Calm settles in. All I can hear is the sound of my own breathing in the scuba regulator. So much planning, hauling, and apprehension have gone into this 2021 mission. For years, I have been imagining what is on the other side of this tunnel, beneath the water. I wrap a dive line around a hold and glide forward, following the contours of the floor. The main passage abruptly ends in an alcove. I backtrack to an upward shaft. It narrows around my shoulders with sharp, crumbly rock. I contemplate the ramp that drops five metres down to the north, but I’m already close to the air limits of my tanks. I complete the rough survey and retreat.

Ten years after the discovery of Bisaro Anima, it’s been confirmed to be the deepest cave in Canada at a depth of 683 metres and a length of 6.4 kilometres. Over 40 cavers have participated in its exploration, and although the cave continues underwater, the team is going to focus its efforts on finding a dry bypass. More caves have opened in recent years, possibly due to hot summers and low snowpack.

I’m grateful my 2021 dive was a success and that I was able to reveal a few more of the cave’s secrets, but I am plagued by the dread of what it will take to complete another trip. Still, the excitement of discovery leads me ever deeper.

Related Stories

Diving Into Fernie

KAVU wanted to celebrate the launch of KAVU apparel, bags and accessories in Canada so they spent a weekend in Fernie…

KAVU Canada Lands First in Fernie

On March 22, 2014 KAVU & Elevation Showcase Presents KAVU Canada. KAVU athletes and KAVU staff will be dropping…

Freediving Under Canada’s Frozen Lakes

For Alberta athlete Lorenza Sommaruga Malaguti, freediving beneath ice truly takes her breath away. A two-metre-wide…

Is This The Worst Hockey Helmet In Canada?

Let's give thanks no one wears equipment like this anymore. Because as one East Kootenay man recalls, a little NHL…

A Stroll Through Canada’s Oldest Nudist Club

Tucked into the cleavage of Mount Fromme and the rear end of Vancouver's North Shore, The VanTan Club invites…