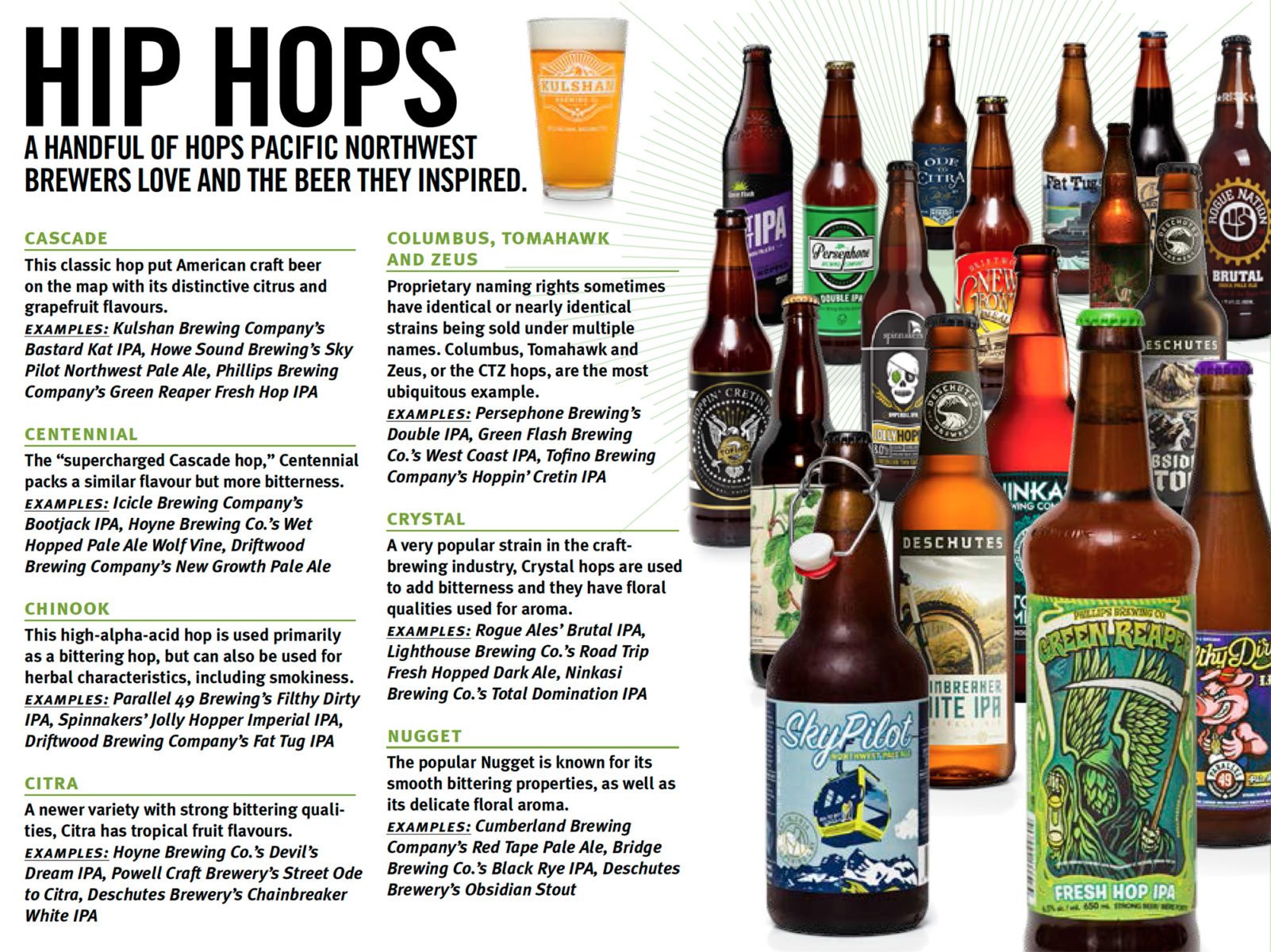

The almighty hop has graced beer with flavour and stability since the ninth century. More recently, the Pacific Northwest’s own bitter-but-blessed holy water — the American-style IPA — has flooded the market and created a divide between craft-beer snobs and some misunderstanding lager louts. We introduce humulus lupulus, a fragrant little flower that makes beer better.

If you had to choose an archetypal label for hop farmer Kevin Lamson, it surely wouldn’t be “beer snob.” The man in the dirty denim and wrinkled ball cap emerges from his Cedar, British Columbia, home with four barking dogs in tow, looking less like an artisan lager fan and more like the Vancouver Island logger that he is. Behind us sits the truck Lamson uses for his day job hauling logging equipment. Behind that are the hanging vines of his second career as owner of Cedar Valley Hop Farm. As small as Lamson and his micro farm appear, they might just be the living embodiment of craft-brewing culture, all of it fuelled by the humble hop. “The local brewers are willing to pay a premium for local hops,” says Lamson. “The small farmers have a chance now.”

Lamson and his wife, Debbie, began to grow hops after a shortage of the fragrant flowering plant hit the Canadian craft landscape in 2008. Faced with a provincial logging industry that was withering on the vine, the Lamsons decided to try and ferment a new career. While Vancouver Island might not be Cascadia’s hop Holy Land — Washington State has that honour, producing around 79 per cent of all American hops — it is a good spot to bust into the beer business on a small scale. After all, almost no one else is doing it like the Lamsons.

The Pacific Northwest is an independent brewing heaven. In fact, the genre currently accounts for almost 50 per cent of British Columbia’s beer sales. Portland, Oregon, boasts more breweries than any other city in the world. Even your neighbour probably has his garage stinking with the next great sour lambic or crisp kolsch in the kettle. Cascadia is high church when it comes to craft, and our holy water is IPA. There is no IPA — no good beer at all, really — without hops. Lots and lots and lots of hops.

Whereas American hop farms average out at 150 acres, with the larger ones running upwards of 1,000, Cedar Valley Hop Farms has seven acres and three part-time employees. When Lamson lists off the breweries he sells to, the names are as obscure as they are local: Longwood Beer, Lighthouse Brewing Company, Wolf Brewing Company, Hoyne Brewing Co., Foundry, Cumberland Brewing Company. All Vancouver Island breweries. All labours of love. All relatively new, some in the last year. And why not? Similar to the foodie and slow-food movements, the small, passionate, local ethos is at the heart of craft brewing.

“Wolf is trying to come up with a 100 per cent local beer,” says Lamson. “But most brewers are buying their hops from a wholesaler down in Oregon. Catch is, you can take a strain of hop out of Mount Hood and grow it here and it’ll be completely different.” What Lamson is talking about is referred to as “terroir” in viniculture or “timbre” in music. It’s akin to the unique element that comes with time and place. The same trumpet sounds different in New Orleans than Seattle. The same grape tastes different grown in Bend versus Lillooet. And hops? Well, when it comes to taste, the way you use hops determines everything. Arguably, the most flavourful — and most contentious — of all beers is the hoppy-as-hell American-style India Pale Ale. Differing from the British original, which is the more subtle-flavoured “Imperial-style” IPA, the American-style boosts the hops effect to the next level, adding bitterness and bite. Many beer aficionados love it. Most regular joes hate it. It even has some legendary detractors in the brewing community.

The Pacific Northwest is an independent brewing heaven. Cascadia is high church when it comes to craft, and our holy water is IPA. There is no IPA—no good beer at all, really—without hops. Lots and lots and lots of hops.

John Mitchell is regarded as the godfather of craft brewing in Canada and the true talent behind the legacies of British Columbia’s Spinnakers and Howe Sound Brewing. He believes the current fascination with ultra-hoppy beers is misguided and misunderstood. “I actually believe we are underhopped here. You can’t taste the hops,” says Mitchell, referring to the American-style IPA’s propensity towards bitterness. “I’m a bit of a purist. I like real hops.”

When Mitchell says “real hops,” he means the actual hop flowers. On the phone from his North Vancouver home, Mitchell rallies against concentrated hop pellets and the brewers who abuse them. It’s a fair point. The hop has been used for more subtle brewing purposes for centuries, and Mitchell regards the hop as paramount to good beer. He just wishes brewers would exercise restraint. So do most lager-swilling barflies in their 60s: imagewise, IPAs are hardly the working-man’s brew. It’s the variety of beer most often aligned with the oft-maligned, tattooed, Portland Community Clown College graduate who brings his own record player to the brewpub after a day of LARPing in Tom McCall Park. But it wasn’t always that way.

If anything typifies craft brewing—both regionally and globally—it’s doing things differently. Craft brewers are defined by their drive and ability to follow their heart’s content at whatever the cost. Indeed, it’s probably why so many of them fail.

Hops were primarily used for flavouring in brewing as far back as the ninth century, and it wasn’t until the early 19th century that English brewers used the fragrant flowers for their stabilizing quality, creating the lightly hopped India Pale Ale so it could withstand the long ocean voyage to colonizing, imperialist Brits stationed in India. While it became a favourite of English drinkers and still is to this day, the original Imperial-style IPA is largely ignored by craft brewers in the Pacific Northwest, who instead prefer the hyper-hopped versions that polarize brewers, drinkers and retailers into two camps: those who revel in the bitter, overpowering citric taste, and those who downright hate it. Indeed, there’s never been a bolder beer in the mainstream marketplace than the American-style IPA, and the Pacific Northwest is both the birthplace and the epicenter of this cult.

SO WHY DO Cascadians love hoppy beer? The lush farmland that lives in the rain shadow of the Coast Range and the Cascades probably helps; historically, hops have been grown from Brackendale, British Columbia, to the Willamette Valley in Oregon, but like terroir or timbre, maybe it goes beyond that. “Culturally, we are different people,” says Paul Hadfield, who, alongside Mitchell, is co-founder of Spinnakers, Canada’s first brewpub. “We’ve been marginalized here, but we’re not bound by traditions. For example, in Quebec or Europe, the depth of the tradition in religious heritage is huge. The artisan food and drink traditions there developed around the church and what the monks needed. They brought that with them from Europe. We got to create it all in Cascadia. It evolved from a sense of place.”

Of course, the idea that the Americanstyle IPAs are a hoppy product of the Pacific Northwest environment doesn’t have to disrespect English ancestry. Rather, it’s a declaration of the West Coast spirit for experimentation. “We appreciate that the brewers in the UK and Europe are the guardians — the keepers of the styles — cool on them,” says Hadfield. “But how boring to faithfully reproduce the recipe so you can hand it off to the next generation intact. We get to go drink it, bring it back, twist it to our liking and make it our own.”

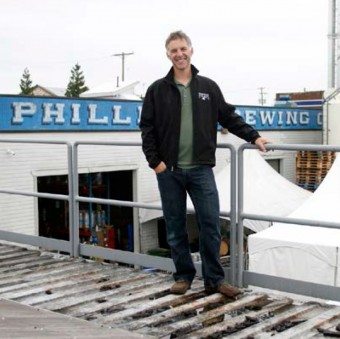

If anything typifies craft brewing — both regionally and globally — it’s doing things differently. Craft brewers are defined by their drive and ability to follow their heart’s content at whatever the cost. Indeed, it’s probably why so many of them fail. But some have succeeded. “We’ve been fortunate enough to be self-indulgent in the kind of beer we make,” says Matt Phillips. The indulgence Phillips speaks of is typified across the industry, where they clamour to come up with the newest, best beer or to dig up and revive an ancient style. For Phillips, the indulgence is manifesting all around us in the whirring circular saws and smashing hammers of a busy construction crew. We’re standing inside what will become one of 21 malting plants in North America, and it’s being built in Phillips’ own backyard. It’s a luxury no other craft brewer in the Pacific Northwest enjoys. Most companies — big and small — buy their malt from malting conglomerates.

Phillips Beer is among the most successful of all Cascadian craft brewers. By leading a bizarre, small-scale malting vanguard over buying from a conglomerate, Phillips is making a statement as strong as the funky smell of hops in the air around us. When I ask Phillips if malting makes money sense, he laughs. “Very little of this is profitable,” he says with a smile. “But it’s fun, and I get to control the product.”

Phillips’ dedication to doing things his own way is well-known. In what has now become craft-beer legend, he leveraged a microbiology degree and massive credit-card debt to purchase equipment from one of the many failed breweries that came out of the 90s craft boom, and then he built his own bottling machine by hand. His first batch of 800 bottles was hand-labelled by Phillips himself in the back of a box van during a sleepless night before his first-ever delivery. The fact that one of the first beers he went to market with was a hopped-up one is evidence of the culture’s boldness. “The first beer we put out was an IPA, actually,” says Phillips. “We brewed it in a 1,300-square-foot space and I slept on the floor. We will do 75 beers this year. At least 25 or 30 will be IPAs. The love affair is not over.”

It’s the kind of story craft-beer drinkers love. If anything, the culture rallies around flavour, in its stories and in its creations. The American-style IPA might be the most flavourful of both, but Phillips hopes brewers and drinkers will continue the spirit of exploration beyond hop-centric offerings. “Styles don’t encapsulate the soul of the beer. It’s more than that. It’s more than a spec sheet,” he says. “Beer can’t be a list of chemical components, otherwise we’d just blend it up and package it.”

Phillips looks around the micro-empire he’s built on hops, grain, malt and yeast; he smiles and lifts a bottle of Blue Buck to his lips. “The perfect beer is the beer you want to drink on that particular day, in that particular place with those particular people.”

Related Stories

K ODE ~ Kiesza’s rise to fame

The usual adjectives to describe Kiesza’s rise to fame—rapid, dizzying, meteoric—don’t do justice to the surreal…

Rise of the She Bum, by Lisa Richardson

Without them, the mountains would be truly inhospitable. Take a read into the ethos and beauty of mountain culture's…

This is Why You Should Care About The Rise Of Rogue Media

Editor Vince Hempsall offers a glimpse into the world of rogue media, why we're seeing more of it in our communities,…

Simon Beck Stomps Out Art

In 2012, we covered Simon Beck's incredible snowshoed artwork in KMC. Recently, Icebreaker released a video of his…

Art Director’s Christmas Wish

Chris Rowat, KMC's Art Director, is a very talented man. If not quirky and perhaps ecclectic, like any creative…