We sent our editor to take the Avalanche Skills Training 2 course at a backcountry hut. What he learned is 90% percent of us might not be qualified to be out there. This is why. Story, photos and video by Vince Hempsall.

WHEN I SAW THE CRACK splinter out from the tip of my ski like a bolt of grey lightning ripping through a perfect white canvas, I was elated. I had trained the past five days for this moment and now, finally, I had caused an avalanche.

Conditions were ripe. It had snowed about a half metre in the past week and the temperature had suddenly warmed from a constant -15°C to near zero overnight. We were being cautious but my classmate and I still wanted to see what it was like to kick off a surface slab layer. We chose a 30-metre-high steep convex roll with a well-defined escape route and a wide runout path that was clear of any trees or obstacles. I made sure he had his eyes on me and then dropped in, ski cutting the top of the slope. Within seconds a 20-centimetre-deep slab sheared off under my downhill ski and shot left while I escaped right to safe terrain. The crown made a perfect heart-shaped pattern down and around an exposed rock for 20 metres and the debris ran for 25 metres. I turned back from the safe zone to look at my handiwork and then whooped with happiness.

In most backcountry scenarios, causing an avalanche is something you want to avoid. In this case, however, I was nearing the end of an Avalanche Skills Training Level Two course and, because we were filled with knowledge and had monitored the conditions religiously, we wanted to experience practical application of the lessons we had learned.

It had been an incredible week. Seven of us had travelled to the newly built Lequereux Outpost in the Selkirk Mountains of British Columbia to study with instructor and Rossland resident Keith Robine, who owns Kootenay Avalanche Courses. His hut-based AST 2 course is unique because students are immersed in the backcountry and over a seven-day period his lesson plan alternates between instruction in the field and self-guided days. It’s also a different experience because Keith isn’t guiding us. His job is to mentor and train so we can take ourselves safely into the backcountry.

During my course with Keith I learned more than I have in the past decade but the most surprising realization was this: in order for me to get the most out of backcountry skiing, AST Level 1 and companion rescue training isn’t close to being enough.

CANADA IS ONE OF THE leading nations on earth when it comes to avalanche forecasting, teaching and technology thanks in part to our current prime minister. Justin Trudeau’s younger brother Michel died in an avalanche in 1998 and as a result Justin and his mother Margaret became heavily involved in fundraising and promoting the non-profit Canadian Avalanche Association, which trains and supports professionals who work in avalanche terrain. [Ed note: For more avalanche stats, log on to Ryan Stuart’s excellent article, “How Many Backcountry Skiers Are Out There?“]

The CAA had been around since 1981 but it grew exponentially with the help of the Trudeaus and, in 2004 a separate entity branched off of it with a mandate of delivering avalanche skills training and messaging to the general public. Called the Canadian Avalanche Centre, the offshoot came about because of another tragedy in which seven school kids from Calgary died in a 2003 avalanche in Glacier National Park.

The CAC has since changed its name to Avalanche Canada and is responsible for public education programs and the Avalanche Skills Training courses. “Last year we had 7,439 Canadians enrol in AST 1 and 780 for AST 2,” says Nancy Geismar, the education and outreach coordinator at Avalanche Canada. “It’s always been like that – roughly 10% of AST 1 students go onto further training.”

That’s not enough according to the organization. Nancy continues: “We want instructors of AST 1 to say at the completion of the course, ‘Look, this is just the beginning. You really need to practice this year and I want you to come back next year and continue your training by doing AST 2.’ But we understand the discrepancy in numbers because AST 1 is a weekend course that’s super easy and it fits into work schedules. AST 2 definitely takes more time (usually four days), planning and commitment.”

Nancy says Avalanche Canada wants more people to enrol in AST 2 because there are more skiers in the backcountry than ever before, which means an individual’s actions not only impact themselves and their group but complete strangers who might be skiing nearby. Plus she says AST 1 is meant to be a primer — kind of like getting your learner’s license. In order to confidently navigate avalanche terrain, you need a full license and that only comes with one of two things: a decade’s worth of practice or an AST 2 course. And what better way to learn then taking a course at a backcountry hut that’s immersed in the type of terrain you’re studying? “What Keith does with his hut-based AST 2 course is definitely value added because you’re out there for seven days and all you do is ski, sleep and eat,” Nancy says. “You don’t have to go to the office or drive anywhere.”

THE COURSE I HAD ENROLLED IN with Keith Robine took place at Lequereux Outpost, the third in a series of lodges owned by Shelly and Martin Glasheen of Valkyr Adventures. The couple have lived in Fauquier, British Columbia, since 1978 and built their first lodge near Naumulten Mountain in the Valkyr Range in 2004. Eight years later they opened the luxurious Hilda Hut near Hida Peak and this year they completed the Outpost, which is a more rustic experience that’s “designed for the DIY Crowd,” Shelly says. The Outpost has eight-bunks, a wood-burning stove and a propane oven, stove, fridge and overhead lights. It also has a sauna but unlike their other lodges, it doesn’t have indoor plumbing so guests must collect water from the nearby lake and use an outhouse.

When asked about offering AST 2 courses at their various backcountry establishments, Shelly says, “It’s a really good pairing. Keith has come to all of our lodges over the years and recently he focused on teaching AST 2 at Hilda Hut. This is the first year of him going to the Outpost to teach…overall it’s a really good match because students get right out there in the terrain.”

Then my classmates buried me alive. They did such a good job packing down the snow above me I couldn’t move my body at all. The world under the snow was pitch black and eerily quiet. No wind. No sounds of boots scrunching on the snow. Just my breathing, ragged at first and then, eventually, deep and even.

Indeed. It’s a ten-minute helicopter ride from the staging area at Burton, on the shores of Upper Arrow Lake, to the Outpost at the base of Mt. Lequereux and the second we stepped out of the helicopter we were at 2,200 metres and in full-on alpine conditions complete with blowing wind and a three-metre-deep snowpack. After loading our gear inside the cabin, we immediately began our training, which included a companion rescue refresher. Students took turns searching for, probing and digging out a buried transceiver, which was made all the more real with the howling wind and whiteout conditions.

We then practiced digging out a buried “body” as a group and once the hole was complete, Keith invited one of us to get in and see what it’s like being buried in an avalanche. Other than the sound of the wind he was met with resounding silence. Be buried voluntarily? Nope. But then I thought about it and realized it was the perfect, controlled environment to come to grips with a primordial fear. So I crawled into the two-metre deep hole, tucked into the fetal position, created an air pocket in front of my face and held on to a probe so, should I lose the plot, I could use it to signal the group and get dug out immediately.

Then my classmates buried me alive. They did such a good job packing down the snow above me I couldn’t move my body at all. The world under the snow was pitch black and eerily quiet. No wind. No sound of boots scrunching on the snow. Just my breathing, ragged at first and then, eventually, deep and even. It’s not so bad being buried alive knowing a team is standing five metres away counting the seconds until they can uncover you.

“What Keith does with his hut-based AST 2 course is definitely value added because you’re out there for seven days and all you do is ski, sleep and eat. You don’t have to go to the office or drive anywhere.” – Nancy Geismar, Avalanche Canada

I was only buried two minutes and for most of it I remained calm but when I heard the sounds of shovelling above me I wanted nothing more than to move. But I couldn’t. I yelled but it was like shouting into a pillow. Panic started to set in but suddenly the snow above me changed from black to a shade of blue, like glacier ice. Finally, I was able to move my arm and brush snow away from my face. I emerged to the concerned looks of my fellow students and Keith asked that I share the emotions of my experience. Lesson one was complete.

KEITH IS A NATURAL WHEN it comes to outdoor instruction. He’s athletic but has a soft-spoken way about him that encourages openness. “I’ve always been drawn to teaching,” he says in an accent that hints at his New York roots. He has a master’s in environmental engineering from Stanford University but later decided to go back to teaching and worked with Colorado Mountain College and Outward Bound. Soon after meeting Ann, his wife, he moved to Canada and settled in Rossland where he now divides his professional time between youth counselling and avalanche course instruction.

“I get a lot of satisfaction with this work and knowing people have a solid framework with which to continue their skills in the backcountry,” he says, “but it’s a lot broader than that. People have the opportunity to learn life skills such as communication and navigating group dynamics.”

During the week-long AST 2 course, Keith’s lessons and field trips were interspersed with self-guided days. On Monday we skied into the treeline, learning as we went about avalanche hazards, weather and snowpack conditions, terrain traps, slope angles and more. That evening involved classroom studies and then we split into two groups and created trip plans for the following day, which Keith then approved. Tuesday saw us applying our newly acquired skills on the slopes of the surrounding mountains and constantly communicating about what we observed and where our comfort levels were at.

According to Nancy Geismar at Avalanche Canada the organization is considering changing classifications of AST 1 & 2 to modules of one course rather than separate programs, which means individuals wouldn’t get AST certification until both are completed.

Wednesday involved another field trip with instruction and Thursday was a self-guided day. Friday was when everything came together and we skied into the alpine under Keith’s watchful eye, navigating around cornices and convex rolls through howling wind and near-whiteout conditions. That was the day our confidence as a group and as individual backcountry skiers really consolidated. The AST 1 curriculum may have taught me how to dig out a buried partner, but it wasn’t until AST 2 that I started to truly feel comfortable skiing in the alpine.

“AST 1 courses are incredibly popular and rightfully so,” Keith says. “But people do them and think that’s it, they’re done. They’re expert backcountry skiers now. But AST 1 is just part one of the whole process and you’ve not really completed the training until you do part two.”

According to Nancy Geismar at Avalanche Canada the organization is considering changing classifications of AST 1 & 2 to modules of one course rather than separate programs, which means individuals wouldn’t get AST certification until both are completed.

Until then, ninety percent of those who have graduated AST 1 may be under the false belief they’re certified to competently navigate backcountry avalanche terrain. In my experience, that’s not the case. My AST 1 training and ten years experience were nothing compared to a week of AST 2 instruction at a backcountry hut. I now have a foundation with which to assimilate forecasts, study snowpacks, navigate alpine terrain, identify traps, and consolidate climate data. And avoid avalanches.

Vince Hempsall

Vince Hempsall lives in the beautiful mountain town of Nelson, British Columbia, where he spends his time rock climbing, backcountry skiing and mountain biking (when not working). He is the editor of Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine and online editor for the Mountain Culture Group.

Related Stories

Calving Glaciers and Chasing Ice

This is oddly beautiful. The destruction, of course, is terrifying. At Coast Mountain Culture, we've watched an advance…

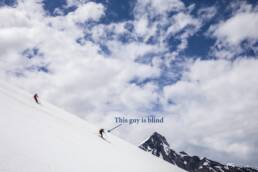

Tyson Rettie is taking blind people backcountry skiing. This is how.

With his Braille Mountain Initiative, Tyson Rettie is introducing visually impaired skiers to the backcountry. By Ryan…

How Many Backcountry Skiers Are Out There?

Over the last 20 years, the backcountry has seen a massive spike in use. From sledders to shredders, on any given…

Skiing World Loses a Bright Light: Dave Treadway Perishes in Backcountry Accident

It's with heavy hearts we share the loss of legendary Canadian skier, and our bud, Dave Treadway. Rest in peace,…